|

Baby boomer hang on, and echo boomers enter the

scene

by Allen Best

|

X-Rock, a popular climbing

area north of town on the flanks of Animas Mountain, and 2.45

acres surrounding it, was bought as open space in April 2001.

Durango’s Open Space Advisory Board is looking at ways

of securing a permanent fund that would go

toward the purchase of more open space, such as the X-Rock

parcel, in the future./Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

Many ski areas currently have the closed sign out. But behind

closed doors, ski area managers across the United States are looking

at better times. After sputtering for two decades, the industry

is finally growing once again. For ski areas, it’s not just

a matter of stealing market share from one another. The pie of

customers has actually been getting bigger, the first time since

baby boomers came of age 25 years ago.

Consider the last three years. There was terrorism. Stock market

pneumonia. And war – not once, but twice. These things should

have been disasters for the ski industry. Instead, the U.S. ski

industry had three of its four busiest seasons ever during this

time, the first prolonged growth since numbers began flattening

in 1979.

Population demographics have begun to favor the industry once

again. The 78 million baby boomers, now aged 40 to 58, are lingering

on the slopes longer than expected. They are more healthy and

vigorous than any generation before, and shaped skis combined

with improved grooming may keep them on boards 10 years longer

than originally expected.

Echo boomers, aged 21 and younger, are now dancing onto center

stage, about 71 million strong, providing nearly as much punch

as the original boomers. If the ski industry can get this generation

as interested in snow sports as their elders have been, the good

times will roll.

Michael Berry, president of the National Ski Area Association,

is upbeat. He traces the surge back to the 2000-01 season. From

the previous high of 54 million skiers in the United States that

had been the benchmark for a decade, the national tally leapt

to 57.3 million. Added to that were a record 14 million skiers

in Canada.

After the Sept. 11 attacks in 2001, the near halt in long-distance

travel and the stock market skid did not deflate skier numbers

as might have been expected. Instead, numbers held at 54 million.

Then, during the 2002-03 season, despite the outbreak of war against

Iraq in March, numbers jumped again to a new record of 57.6 million.

Berry says he wouldn’t be surprised if U.S skier numbers

surpassed 60 million within the next few years.

“We would expect this growth to continue for five to 10

years – that’s what the demographic data are telling

us,” says Berry.

Growth at small ‘urban’ areas

So far, nearly all the evidence for growth is found at smaller

ski areas near cities. A third of the 735 ski areas that existed

20 years ago have now closed, most of them smaller places, often

in places of marginal snow conditions. But now, the small ski

areas are thriving, and there are a few new ski areas.

Consider Colorado’s Eldora Mountain Resort, a smallish

ski area west of Boulder. A decade ago, Eldora was doing about

135,000 skiers annually, all of them day visitors from Colorado’s

Front Range. In the last several years, Eldora has been squeezed

by cheap season passes offered by Vail Resorts and Intrawest at

destination resorts not much farther away.

Still, by last year, Eldora’s numbers had essentially doubled

to almost 290,000 skier days, nearly the same as Aspen Mountain.

Such increased business is common at small ski areas close to

cities across the United States, reports Berry. They’re

doing so well that, at times – during school vacations,

holidays, after-school programs – there’s a capacity

problem.

Easily explained

All of this, says Berry, is easily explained.

“It’s all attributable to the demographic reality

that there are a lot of kids under 20,” he says. “We

expect to see this phenomenon continuing for between five and

10 years, and we have actually focused a lot of effort in the

industry to make sure we take full advantage of this opportunity.”

But Ford Frick, an economist and a principle in Denver-based

BBC Research and Consulting, argues that the industry may be growing

because it has broken free of its stuffiness. In his industry-commissioned

paper, “The American Ski Industry – Alive, Well and

Even Growing,” he argues that snowboards have been the key

agent of change.

|

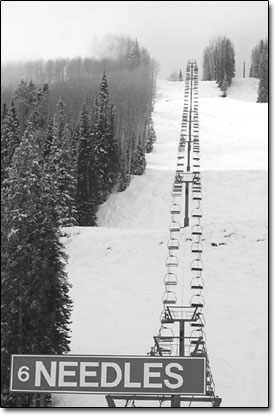

Skiers ride the DMR Six Pack earlier this

season. Ski area officals are lauding the

recent growth in skier numbers, saying that after years of

no growth, the sport

is growing again, thanks in part to the continued health of

baby boomers and the

so-called echo boomers, those age 21 and younger./Photo by

Todd Newcomer. |

“The introduction of snowboarding and the rapid rise in

telemark skiing, free skiing and a number of other equipment variations,

have been a breakthrough for the ski industry – not just

because they drew a new generation of participants, but because

they reminded an increasingly stodgy industry that ‘skiing’

was fundamentally about unstructured, outdoor recreation and the

individual freedom and adventure that it offers,” says Frick.

Vail, Crested Butte, Breckenridge – just about wherever

you go, the story is the same. Ski resorts are doing things that

were unimaginable a few years ago in an attempt to hang onto baby

boomers while reaching for the new crowd of what might be called

Xtylers.

Rainbow slopes

The ski industry does face a major challenge. If it is to grow,

it must broaden its appeal to a nation that is steadily becoming

more culturally and racially diverse.

In 1970, mid-way through the ski industry’s last boom,

whites made up 83 percent of the U.S. population. At the century’s

turn it was 69 percent. By mid-century, says the U.S. Census Bureau,

it will be 50 percent.

In the next 45 years, the Asian population is expected to triple.

But by far the largest minority group will be Hispanics, at about

25 percent of the U.S. population.

With such evidence in hand, Roberto Moreno, a Denver-based activist

and former ski patroller and instructor in Colorado’s Summit

County, says the ski industry must reach out to minorities.

“If we don’t, we will turn snow sports into polo,”

says Moreno.

“Last year’s jump to 57 million skier visits nationally

was an anomaly, and more the result of the proliferation of discount

season passes,” he maintains. “In fact, the actual

number of snow riders in America is decreasing. What isn’t

an anomaly is this country’s growing multicultural and gay

population.”

The ski industry, charges Moreno, has been only too successful

at marketing its exclusivity. It’s now time to become inclusive,

he insists.

When asked to talk about how to recruit minorities to skiing,

many people of varied backgrounds use the same words as if speaking

from a script. The industry, they say, must make the “invitation.”

Extending this hand to minority groups is not easy, say those

who market skiing, but neither is it rocket science. Mostly, it’s

hard work. The hand shake requires work by both ski area operators

and minorities.

Here and there are success stories. Aspen Skiing Co.’s

Chief Operating Officer David Perry recalls that when he was at

Whistler he helped attract Chinese skiers from Vancouver. The

key was working with group tour operators, he says, and then accommodating

the entire families, even if only the youngsters were learning

to ski and snowboard.

In California, Booth Creek’s Marketing Director Julie Mauer

reports a parallel program that has delivered Asian-Americans

to Northstar-at-Tahoe and Sierra. Studying California demographic

trends in the mid-1990s, Mauer noticed the rapidly increasing

number of immigrants from Asian among the Bay Area’s 11

million residents. Even more important, they had two key characteristics

of traditional skiers: They were highly educated and relatively

affluent.

Through targeted events, such as celebration of the Chinese New

Year, and target groups like social clubs that cater to Asian-Americans,

Mauer has increased the number of young Asian-American professionals,

called yappies, at the Tahoe resorts. From 2 or 3 percent a decade

ago, Asian-Americans now make up 15 percent of the customers at

Northstar and Sierra.

Asian-Americans were “not a particularly hard sell,”

says Mauer. “It’s just a matter of reaching out to

them. It’s not any harder than reaching out to Caucasians.”

More complex puzzle

Latinos, say marketing executives, are a more complex puzzle.

Moreno, now a consultant in such matters, advises the same approach

as with those who have succeeded by working with Asian-Americans.

The ski industry, he says, should establish ties through existing

social and professional groups, “inviting” them to

specific ski areas and into the sport in general. Both affluence

and education levels, note Hispanic activists, are rising.

But Moreno also argues for more diversity among the work force

at ski areas. Imagine going to a resort if you were white and

everybody else was black or Hispanic, suggests Moreno. You would,

at the very least, feel uncomfortable. Yet there are almost no

minorities in front-line positions at ski areas. Same goes for

marketing, such as websites, where minorities are almost nonexistent.

However, Moreno reports he is hearing some things from ski executives

that please him.

Big boys optimistic

Meanwhile, at Colorado’s largest destination resorts, optimism

rules. In Aspen, where there has been no growth at any of its

ski areas since 1992, Perry now predicts growth for five to 10

years.

At Vail Resorts, the story is the same. Adam Aron, chief executive

officer, says he’s far less worried about competition from

new resorts in British Columbia than about nearby competitors

in Colorado with their on-mountain improvements, expanded bed

bases and new base villages. Even so, his conclusion is the same.

“We’re bullish,” he says.

David Barry, senior vice president of Intrawest Colorado, which

operates Copper Mountain and Winter Park, is also upbeat after

double-digit gains in destination visitors this year. “There

are going to be shifts and changes, but I believe that the sport

is healthy, and the sport is evolving and the future is bright.”

|