|

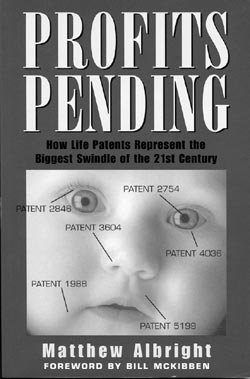

Profits

Pending: How Life Patents Represent the Biggest Swindle

of the 21st Century Profits

Pending: How Life Patents Represent the Biggest Swindle

of the 21st Century

By Matthew Albright

Common Courage Press

234 pages

In her six short years of life, Dolly the cloned sheep

might have raised hopes for people interested in either

shameless narcissism or stem cell treatments. But those

hopes are rapidly deflating as the consequences of biotechnology

are seeping into peoples’ consciences.

Many of those consequences are found in Profits Pending,

a book by local author Matthew Albright. The book is primarily

a scientific look at how gene patenting in the United

States devastates medical advancement more than it fosters

it. Subtitled How Life Patents Represent the Biggest Swindle

of the 21st Century, the book might seem to a naysayer

a whacked-out view based on conspiracy. Unfortunately,

the use of the word “swindle” lends itself

to such a conclusion. However, the book is based on anything

but conspiracy.

Instead, it draws on a variety of scientific data and

discussion from organizations fighting to ensure science

and politics don’t stifle inventions that could

save peoples’ lives. Essentially, Albright writes

about how the U.S. patent system allows corporations,

universities and research institutions to monopolize and

profit from things nature created. In other words, they

are taking human genes, human proteins and other molecules

found in the body and legally protecting them.

As an example, Albright briefly tells readers about the

Greenberg family. Two of the Greenberg children died from

a rare neurological disorder called Canavan disease. While

still only infants, medical researchers used them as a

starting point to begin researching the genetic causes

of the disease. The Greenberg parents and 160 other families

provided blood and tissue samples for the project. Ultimately,

a researcher at Miami Children’s Hospital identified

a mutation of a specific gene that was associated with

the disease. The information was later used to develop

a test to screen for the mutations. In the process, the

hospital successfully patented the gene. But the story

doesn’t result in a cure for the disease. In fact,

it doesn’t even result in significant gain in the

medical community.

By patenting the gene, the hospital restricted, even

altogether denied, other researchers from investigating

Canavan disease. Researchers who used the screening test

were legally bound to pay royalties to the hospital. In

effect, the Greenbergs and other families whose children

died from Canavans handed the hospital a pot of gold.

“What the hospital has done is a desecration of

the good that has come from our childrens’ short

lives,” the father of the Greenbergs told the Chicago

Tribune. “I can’t look at it any other way.”

Albright jumps off from this story to explain that patenting

genes in the name of medical advancement is just a bunch

of hooey, especially since reportedly 10 percent of illnesses

people suffer are caused by a combination of genes, environment

and lifestyle.

Albright writes: “Companies are now patenting diseases

themselves like tuberculosis and staph infection. Instead

of helping to prevent or cure these diseases, however,

the race for these patents engenders secrecy in research

and creates walls between scientists.”

On the surface, the argument for patents seems mostly

clear – that genes must be patentable in order for

firms to recoup their investment in identifying them.

But as Albright goes on to argue, this practice affects

society beyond medical advancement. These patents (known

as “life patents”) threaten the already slippery

slope of intellectual property. They create monopolies

and abuse political power. And because gene patent ownership

is so important to biotech companies’ stock market

valuation, they can cause market upheaval (remember in

2000, when former President Bill Clinton and British Prime

Minister Tony Blair sent biotech stocks plunging by suggesting

that raw human gene sequence data “should be made

freely available”?).

With the varying implications of how we treat genes (be

it for diseases or cloning), there is an astounding amount

of theory, evidence and opinion surrounding these patents.

In his book, Albright does, by and large, an impressive

job of explaining this issue in laymen’s terms.

Usually, he keeps the text to palatable ideas and phrases.

He also provides extensive notes so that readers can judge

for themselves how much of a “swindle” this

is (25 pages of notes in a book with chapter pages that

don’t quite number 200). The only things that bog

down the book are Albright’s subheads and random

quotes by talking heads. Still, these things are not enough

to damn the book to the resale bin.

However, this book does not necessarily have mass readership

appeal. It’s more likely to call out to academics

that enjoy a stimulating dialogue about a topic fit for

a doctoral dissertation. Still Albright works to ferret

out the legalese and extenuating arguments, and he delivers

a message on a complex topic that is more than just about

counterfeit sheep. It’s about how all of our genes

can be easily sold to the highest or swiftest bidder.

|