|

Local boat builder works and lives a

labor of love

by Amy Maestas

|

| Andy Hutchinson displays

his most recent creation, the shell of a new river

dory, inside his workshop Sunday afternoon. Hutchinson,

a Grand Canyon river guide, has been making the wooden

boats for nearly 20 years./Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

Andy Hutchinson prefers to float the massive, flesh-pounding

rapids of the famed Grand Canyon in high-grade plywood.

Never mind the 840/47-denier nylon, the Kevlar or the

fiberglass – those textiles that are ostensibly

the only ones that can withstand the unfortunate boat-bottom-to-snaggletooth-rock

meetings. For Hutchinson, the best trip in this beastly

canyon is layered, veneered wood, which, at first glance,

looks as if just sitting on it will snap it in half.

Not so. Hutchinson declares that the hard-hulled boat

sitting freely on the floor of his shop at the top of

Farmington Hill is brawny enough to withstand the toughest

of rapids in a sometimes unforgiving place. After all,

when Major John Wesley Powell forged the canyon in the

late 1800s, he and his accidental friends did so in nothing

but wood.

But Powell’s boats were unwieldy, keeled, cutwater

boats. What Hutchinson is building is a durable, graceful

dory – one that will glide smoothly down the magnificent

canyon and give its riders an unparalleled float. The

ride in a dory is so famous, so coveted, that this style

of boat is beginning to regain popularity.

For Hutchinson, this means all kinds of benefits; among

them is some income, since he is one of the few dory makers

in the West who custom-builds the boats

|

| A row of ores hangs from the rafters

in Andy Hutchinson's barn./Photo by Todd Newcomer |

upon order. But more importantly, Hutchinson says, it

means reviving the spirits of pioneering river runners.

Only in the past 10 years have dories become a more sought-out

watercraft by river runners in search of a more “organic”

experience on the water.

“It’s kind of a retro thing going on,”

Hutchinson says. “It’s not like my phone is

ringing every day, but there has definitely been a surge.”

During the summer, Hutchinson works as a commercial guide

for Kanab-based Grand Canyon Expeditions. He almost exclusively

rows dories – whether on commercial or personal

trips. During the winter, he runs his business, High Desert

Boatworks.

Water fights and bikinis

Growing up in Salida, Hutchinson routinely drove by the

Arkansas River – the most popular whitewater river

in the country.

“In the summer I saw the guides out there having

water fights and the girls were in bikinis, and I thought,

‘Hey, I want to do that.’”

So he did. In the late 1970s, Hutchinson learned to paddle.

In 1982, he was invited on a Grand Canyon trip. It was

there that he spotted his first dory.

“I saw it, and I was smitten,” he recalls.

Two years later, he rowed his first dory on a winter

trip down the San Juan River. Only a few years later,

he built his first boat.

Hutchinson’s interest in river running pioneers

like Bus Hatch, Martin Litton and Norman Nevills fueled

his dory lovesickness. River historians credit Litton

for introducing whitewater dories to the industry and

the Grand Canyon. Hutchinson even credits Litton for successfully

fighting the Bureau of Reclamation against damming the

Grand Canyon after the agency had already done so with

Glen Canyon Dam by convincing the Bureau how valuable

the recreation industry was and how many people relied

on a free-flowing river.

“The dory saved the Grand Canyon,” Hutchinson

says.

Over the years, several veteran river runners have reworked

and refined whitewater dories. 4 As a baseline, Hutchinson

uses well-known boat builder Jerry Briggs’ designs

to build the 16-foot, 9-inches-long wooden boats that

typically have six hatches, passenger benches and hardwood

rails and trim. The finished product, Hutchinson says,

is a work of art.

“It’s definitely a labor of love. I feel

like it’s my piece of artwork, and I have a hard

time when one of them leaves my shop.”

Hand-making a Grand Canyon dory is time consuming. Each

one requires somewhere around 300 hours – or 2BD

months. This is partly why, Hutchinson says, there are

so few dory builders in the West (fellow Durangoan Derald

Stewart is also among this group). In between river time,

skiing and other outdoor pursuits, Hutchinson ends up

building only one a year. And he is fine with that. Hutchinson

is not keen on having a market flooded with mass-produced

dories. Nor is he solely interested in building dories

just for monetary gain.

For many years, he says, he undercharged customers simply

because he was new to the business and didn’t want

to exploit people. Even now, he winces at admitting he

actually makes a profit building boats.

“Yeah, I guess it’s that part of the river

runner in me,” he says.

|

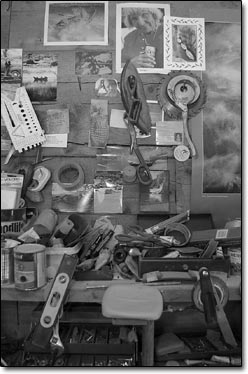

| A collection of tools

and river running paraphernalia litter Andy Hutchinson's

work bench./Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

The Sandra

In the 12 years Hutchinson has been a dory maker, he

estimates he’s built 10 from scratch. But he has

also undertaken at least 25 other dory projects, whether

it’s repair or helping others build. Each dory has

its challenges – and rewards. But none was as challenging

or rewarding as a project he took on in 2000.

Greg Reiff, Norman Nevills’ grandson, called Hutchinson

looking for help. In the late 1930s, Nevills created a

style of dory that was broader than the ones that Utah

trapper Nathaniel Galloway had been building for whitewater

boating. Nevills’ wider dory allowed him to cut

through the strong rapids with skill and safety. His style

of dories was so well liked that river runners used them

on the Colorado River for the next 30 years.

Reiff had found one of Nevills’ boats that he built

in 1947. Named the “Sandra” – after

his daughter (Reiff’s mother) – the dory was

sitting in a back yard, rotting away from age and exposure.

Nevills’ family wanted Hutchinson to restore it.

He agreed – solely because of the emotional rewards.

“It was very humbling,” Hutchinson recalls.

“I mean here’s this boat that was Norman’s,

and I got to bring it back to life.”

Because much of the boat had deteriorated, Hutchinson

had to extensively research how the boat was originally

built. He traveled to river museums, where some of Nevills’

Cataract Canyon boats were on display. Using measurements,

old photographs and a compilation of anecdotes (Nevills

died in a plane crash in 1949), he re-created an icon

of the West.

Ultimately, Hutchinson reconstructed the Sandra using

modern-day materials, such as epoxy and fiberglass. Nevills

originally used wood, screws and caulk. But because Reiff

wanted to float the boat on a river, they decided current

techniques were acceptable. After several months in a

Durango barn, Hutchinson relived history. He breathed

new life into a coveted dory and, to boot, was able to

meet Frank Wright, the Sandra’s main boatman when

he worked for Nevills. When Hutchinson sent the Sandra

on its way, he cried.

“I realized that through Frank, mama Sandra and

Cataract boat Sandra, old rivers and boats do talk,”

Hutchinson wrote in a memoir of the project.

Dory spark

Even without a story like the Sandra, Hutchinson still

believes each dory has its own spirit. When on the water,

he doesn’t often see the dories he builds. They

are far and wide. But if he does spot one of his handmade

crafts, he gets a kick out of it. He says it’s because

he knows how unique dories are to a river experience.

“Rafts are so care free – kind of Tom-Sawyer

like,” he explains. “And though dories are

less forgiving, they give you high performance.”

Yet, he still finds it difficult to explain that dory

“spark.” He can only quote the famous Litton:

“Those who have to ask will never know.”

|