|

Silverton Avalanche School reconvenes

by Shawna Bethell

|

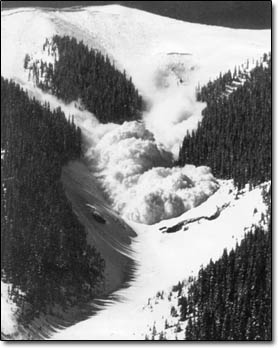

| A large slide rips

down the Battleship northwest of Silverton. Photo

by Tim Lane/courtesy of Living (and dying) in Avalanche

Country. |

The cold morning air follows the barely awake students

as they stumble up the old wooden stairs of Silverton’s

Miners Union Theatre. Clothed in layers of fleece and

GoreTex and carrying travel mugs of coffee, they talk

amongst themselves and find a seat in the chilly auditorium.

The students begin to awake as the big screen in front

of them flashes shots of skiers and boarders laying down

first tracks, snow scientists digging pits and masses

of snow crashing down mountainsides. These things set

the stage for the reason these students have come to the

Silverton Avalanche School, the oldest avalanche-awareness

program in the country.

At the back of the room, leaning unobtrusively against

the wall, arms crossed at his chest, legs crossed at the

ankle, stands a man in Carhartts, flannel shirt and wide-brimmed

hat. His blue eyes scan the events on stage and the

|

A Silverton Avalanche

School

instructor, Larry Raab has been

instructing for more than 20

years./Photo by Dave Fiddler. |

audience. He is repeatedly greeted by instructors back

for another year and shakes hands with old friends. Larry

Raab has seen this all before but can never quite stay

away from the school, the weekends of student excitement,

the gathering of the subculture of snow enthusiasts and

backcountry adventurers. He’s been doing this for

more than 20 years, and before that he was just as untamed

as the youth in the audience.

Sitting in the kitchen of his Silverton home, Raab grins

when asked about his history with the school, and he looks

at his wife, Rose, who gives him that “raised eyebrow,

knowing look.”

“Rosie actually took the school first,” Raab

says. “That was back in ’75. At the time,

I was more interested in peak-bagging, myself. I didn’t

get involved ’til ’76.” He explains

that he was young and foolish and loved the backcountry,

climbing in leather hiking boots or snowmobile boots and

skiing on old military, cable-binding type skis.

“I never had good equipment, just whatever was

available to get out there,” Raab says. “Me

and my climbing partner were doing crazy things in those

days. Rose forced me to take the class.”

Standing at the stove, Rose heats water for tea, and

you can see her remembering the early days in this “anything

goes” mountain town.

“I figure if we are going to live up here, we better

do it right,” she says.

The

Silverton Avalanche School returns for

its 38th year next week. The school offers Level

I and Level II courses that meet the American Avalanche

Association’s (A3) requirements for course

curriculum, and Silverton’s instructors are

nationally recognized members of the Level I focuses

on rescue theory, terrain recognition, use of avalanche

transceiver and decision making. The three-day courses

feature classroom lectures and fieldwork, and Sundays

are slated for a backcountry tour emphasizing decision

making and terrain recognition. Level II focuses

more on snow science with courses in

data pits, stability, snowpack and crystallography.

There are openings in a Level I class Jan. 30-Feb.

1 and a Level

II class Feb. 6-8. For more information log onto

www.silvertonavalanche

school.com or call Bruce Conrad at 387-5018. |

Country’s best classroom

San Juan County, and especially the U.S. Highway 550

corridor, is the most avalanche prone area in the lower

48 states. It also holds the eerie prestige of having

the most avalanche deaths in the United States notched

on its proverbial belt. This is precisely why Silverton

Avalanche School, set in the heart of this avalanche terrain,

is the country’s best classroom for avalanche study.

“The San Juans are an excellent place to study

avalanches because of the numerous avalanche paths and

the typically unstable snowpack,” says Andy Gleason,

Colorado Avalanche Information Center Forecaster, Silverton

Avalanche School instructor and all-around snow guru.

Gleason has spent years studying the unique snowpack

of the San Juans, trying to stay one step ahead of Mother

Nature and keep the highway safe. “We sit in a continental

snow climate which is conditionally unstable and produces

4 lots of full depth ‘climax avalanches’ during

a typical snow season,” Gleason explains. Climax

avalanches are those in which the entire snowpack empties

from the slide area.

|

| A Silverton Avalanche

School student isolates a column of snow and performs

a shovel shear test during the 2003 session./Photo

by Dave Fiddler. |

Rescue or recovery

Silverton Avalanche School started in 1962 when the Highway

Department, Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management

and Fish and Game Department decided their employees needed

avalanche training to keep themselves safe. Fifty students

gathered in Silverton for the first Avalanche and Winter

Survival Workshop. The School remained institutional in

nature until 1982 when it was taken over by San Juan County

Search and Rescue. With the change came an increased enrollment

of backcountry enthusiasts and the philosophy of self-rescue.

“Under most circumstances,” Raab says, “you

have a window of 30 minutes for probability of survival

with an avalanche victim. You need to know how to save

yourself or save your buddy. If you’re in the backcountry

and you have to go for help, the scenario has changed

from rescue to recovery.”

Raab recalls when he woke up to the importance of avalanche

awareness. He’d been called out on an avalanche

recovery on Jura Knob, north of Engineer Mountain, where

the torrent of snow and debris had not run a straight

line down the mountain. It had turned. The victim’s

buddies had searched the area all day and finally reported

it to Search and Rescue that night.

“It was blizzard conditions and dark before they

reported, so the next morning the team was helicoptered

in,” he said. A rescue dog named Leo found the man

in about five minutes at the edge of the slide in a terrain

trap.

“He’d been swimming and had almost reached

the surface,” Raab said. “There was only about

an inch of snow covering his hand, just scuffing over

his fingers. They’d have found him in time if they’d

known where to look. All the clues were there.”

After 20 years’ experience with the school, doing

everything from directing the school to teaching probe

lines, Raab says the mentality of the students hasn’t

changed. The thrill seekers who play in the snow today

are pretty much the same as those who came 30 years ago.

What has changed is the amount of research that has allowed

for a better understanding of snow science. Regardless,

a recent study in Canada showed that 75 percent of avalanche

fatality victims had received some avalanche-awareness

training. The Silverton Avalanche School took that to

the table and adjusted its curriculum accordingly.

“People need to understand that backcountry travel

is a constant series of decisions,” says School

Director Bruce Conrad. “As avalanche educators,

we need to instill this mentality into our students, as

well as provide them with the tools necessary to make

the decisions that will keep them alive.”

Survivor stories told over and again reflect that the

draw of first tracks often overwhelms logic and good planning.

All the knowledge of snow stability and terrain recognition

in the world won’t do any good if the human ego

steps in.

|