|

Parents struggle to secure spots, cover costs

by Colleen Valles

|

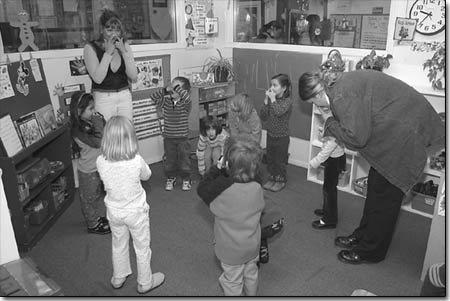

Instructors Molly Davis, left,

and Callie Rickerman sing an audience-participation song with

their group of 5-year-olds at the Durango Early Learning Center

on Monday. The center is one of 23 licensed day-cares in Durango,

where some families have to wait up to a

year for a spot for a child./Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

Isabel Viana knew finding child care in Durango was going to

be hard.

With only 23 licensed day-care centers and 14 licensed home providers,

some parents can wait up to a year for a spot to open for their

child.

So Viana developed a game plan: pound the pavement and be persistent.

When her daughter Zoe, now 3, was just 6 months old, Viana took

her to child-care providers throughout Durango and interviewed

the directors.

“I was very picky and still am,” Viana said. “I

wanted to find a place I liked.”

Viana decided she wanted Zoe to attend the Durango Early Learning

Center, a school licensed to care for children up to 10-years-old.

When Zoe was 8 months old, Viana put her on the waiting list

at the center which at that time, accepted only students over

the age of 2 BD. Then came the second half of Viana’s plan,

the persistence part.

“I just kept checking with them every month,” Viana

said. “I’d come by with Zoe and say I just want her

to get used to the place.”

Viana, a freelance writer who works from home, needed to put

Zoe into child care so she could get some work done.

“For three years, I couldn’t (work),” she said.

“It was just an illusion.”

Viana’s plan finally paid off. Two months before Zoe’s

third birthday, the center had an opening for her, and Viana seized

it.

Getting her daughter into child care “was an ordeal,”

Viana said. “But I was prepared.”

Even with all the preparation, no one is assured a spot in the

school of his or her choice, and often even finding a place with

a licensed child-care provider is a crap shoot.

At capacity

That’s especially true for those who aren’t prepared

and who don’t have 2BD years to spend trying to get their

children into day care. Many wind up turning to relatives and

friends or unlicensed strangers.

The shortage of licensed providers in Durango is acute.

“As far as I’m concerned, that’s the biggest

problem,” said Shannon Bassett, child-care resource and

referral coordinator for La Plata Family Center’s Coalition.

“I get probably five calls a day from people who have already

tried calling everybody.”

Linda Ramirez, the director of Children’s World, said the

biggest need is for care for infants and toddlers. Children’s

World is at capacity right now, she said, with 26 families.

“We have a really long waiting list,” Ramirez said.

“We feel so bad. We have people on there for a year.”

The cost of care

And once a child gets one of the coveted spots, there’s

no guarantee parents can afford it. “The wages in Durango

are lower,” Ramirez said. “We charge $30 a day. That’s

hard for some parents to afford.”

|

| Morgan Martinez, 2, dips her paintbrush

into a Dixie cup at the Durango Early Learning Center on Monday

morning./Photo by Todd Newcomer |

At child care centers in Durango, the average price for infants

is about $30 a day, $28 for toddlers and around4

$26 for kids aged 3 to 5, Bassett said.

The prices generally are lower with home-care providers. And

prices typically decrease as a child gets older because state-mandated

ratios for students to teachers increase. There must be one teacher

for every five infants, whereas there can be more toddlers to

one teacher.

Parents can apply for financial help from the county. Income

and whether parents are working, looking for a job or going to

school are factors in determining eligibility.

Income eligibility depends on household size. For example, for

a family of four, the eligibility level is $2,300 gross monthly

income.

“It’s really hard for a two-parent household (to

get county aid) because of the low income limit,” said Debbie

Berry, a senior resource advisor for the county’s program.

The county has about 160 families in its child care programs,

she said.

And providers are not getting rich off the situation either.

“It’s a high overhead,” said Rachael Sharp,

director of River Mist child-care center. “Unless you have

alternative sources of income, it ends up in the tuition.

“It seems expensive to parents and like low pay to staff,”

she added. “It’s something we’re working on

in the early child-care community.”

In the meantime, there’s a high turnover in early child

care employees because of the pay rate, Bassett said.

Checking licenses

For parents who can’t find licensed help, the county has

a program in which an unlicensed friend or relative willing to

provide the care can contract with the county and get paid, although

the pay is typically lower than what day-care providers generally

make.

But for some, it’s a better option than going with an unlicensed

stranger.

Licensing is done by the state and includes background checks,

training courses on how to care for children and medical courses,

such as CPR and first aid. To maintain the license, training in

each area must be renewed on a regular basis.

Unlicensed providers have no such training and no state-conducted

background checks.

By law, however, unlicensed providers cannot run full child-care

centers from their homes. The law says that an unlicensed provider

cannot care for more than two families’ children on a regular

basis.

Many of Durango’s child-care centers also offer curricula,

so the children are learning as they’re being cared for.

But for some, the main thing is not early education, but simply

qualified care.

“In some cases, we have people who want to be here because

they know the staff; they know our programs,” said Callie

Temple, a teacher at Durango Early Learning Center. “And

other people come because it’s the only place they can get.”

Persistence pays off

Jeanne Szczech was looking for a place where her two daughters

could get a school experience.

She moved to Durango in July from California, but started calling

child-care centers in May. In California, waiting lists aren’t

common, she said.

But here in Durango, Szczech’s persistence paid off.

“I called religiously every week so they would remember

my name,” she said.

Her 4-year-old daughter got into the school in August, and her

2BD-year-old daughter started at the end of October.

Szczech, a mortgage broker who works from home, was lucky. Child

care wasn’t imperative, but she wanted her two girls to

have a school experience. They attend twice a week.

“People are on multiple lists,” she said. “I

knew I had a great shot because I only needed two days a week.

Five days a week, full time – that’s difficult.”

For many parents, it seems impossible, and all they can do is

wait.

|