|

Durangoan converts diesel engine to run

on used fryer grease

by Amy Maestas

|

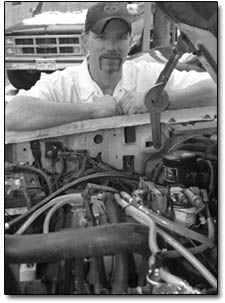

| Odin Thunstrom, left,

of American Made Automotive, and truck owner Craig

Holliday pose Tuesday in front of the Ford diesel

that Holliday converted to run on fryer grease with

the help of Thunstrom. The frenchfry- grease powered

truck gets 15 miles to the gallon./Photo by Todd Newcomer.

|

On a freezing morning, Craig Holliday is hovering under

the hood of his white Ford pickup, watching the same vegetable

oil that his father used to fry a Thanksgiving turkey

course through the tubes leading to his diesel engine.

The faint odor of diesel fuel lingers in the air until

the truck warms up – and then it smells like McDonalds.

Or, for that matter, any of your favorite greasy, fast-food

restaurants.

After a few minutes, Holliday, his mechanic, Odin Thunstrom,

and I climb into the double-cab and drive off on the snow-packed

roads in north Durango. When we narrowly avert a crash

with a snowplow, Holliday turns off the main drag and

begins cruising the alleys a block away. He’s looking

for the coveted black drum barrels behind restaurants.

Inside the barrels is, literally, how Holliday gets around

town.

The truck is full with the strained oil from his father’s

turkey, so Holliday doesn’t stop and take out the

12-volt pump he uses to extract the discarded fat. But

we still bumble down the alleys while the truck bounces

and rocks as though it’s burping – because

it sort of is. Holliday and Thunstrom tell me there is

air in the fuel lines, creating anything but a smooth

ride right now. But once the air works its way out, the

truck runs smoothly, with as much power and panache as

a diesel can have, even though it was converted recently

to a more environmental and economical means of transportation.

Just two weeks ago, Thunstrom finished installing a conversion

kit in the 1991 F-350 that Holliday bought specifically

for this project. The kit was $700, which Holliday bought

off the Internet. The labor was an extra $800. Thunstrom

estimates that if Holliday drives about 20,000 miles a

year, getting 15 miles per gallon, he’s likely to

save about $2,300 a year in gas.

“That means I get my money back in what I paid

for the kit,” says Holliday, a former high-school-teacher-turned-contractor.

More importantly, though, Holliday says he achieves the

goal of being less dependent on foreign oil sources and,

hopefully, arousing local interest about alternative fuel

solutions.

The politics of vegetable oil

Using vegetable oil as an alternative fuel source is

hardly a new idea. But it is a newly popular idea. In

1900, German mechanical engineer Rudolf Diesel invented

the engine that bears his name. He built it to run on

peanut oil, all the while envisioning a world of farmers

growing their own fuel. Peanut oil as gas never took off

the way Diesel hoped it would. But in subsequent years

after his suspicious death, Diesel’s alternative

fuel proposal was much more accepted and implemented in

Europe than in the United States.

Over the years, Europeans realized the benefits of vegetable

oil: it is biodegradable, nontoxic and derived from a

renewable resource. It also reportedly improves gas mileage

by more than 3 percent and reduces smog-forming nitrogen

oxide emissions by 75 percent. Today, various energy organizations

report that there are about 2,000 biodiesel pumping stations

throughout Europe. Biodiesel is a mixture of vegetable

oil, alcohol and catalyst. Just like other forms of petroleum,

it is sold by the gallon from pumps and can be poured

straight into the fuel tank of any diesel vehicle.

While Holliday is attracted to the efficiency of getting

his oil free and saving what could be thousands of dollars

on gas, he’s more engrossed in the idea of getting

Americans to stop relying on vanishing fossil fuel resources

from foreign countries.

Earlier this year as the United States invaded Iraq,

Holliday said he paid especially close attention to the

country’s intentions – however masked they

might have been. He is more inclined to believe that the

war is rooted more in protecting oil sources than banishing

terrorism or securing freedom. Holliday says his older

brother serves in the U.S. Army and is on the waiting

list to be sent to Iraq.

“He’ll be going over there to fight for our

oil,” Holliday says. “All these guys are giving

their lives for oil. We are blowing up Iraqis and Americans

just to make sure we have enough oil for gas. For me,

it’s just wrong.”

Holliday felt compelled to make a political statement.

He began researching the fuel alternative in the spring,

seeking out publications and demonstrations, like the

one he saw at the Earth Day celebration at the Smiley

Building. At the event, Holliday met

|

| Thunstrom stands behind

the vegetable oil converter he installed in Holliday’s

truck. The kit cost $700 on the Internet./Photo by

Todd Newcomer. |

Charris Ford, a well-known Telluride resident who has

vociferously espoused the benefits and necessity of biodiesel

fuel. Calling himself the “Granola Ayatollah of

Canola,” in the past couple of years Ford has been

featured in numerous publications, shedding light on the

idea. Ford’s enthusiasm inspired Holliday, he says.

But still, the gnawing feeling of fighting a war for oil

– which Holliday believes the invasion of Iraq is

about – propelled him to “walk the talk.”

“My inspiration is more Ghandi than Charris,”

Holliday says.

The finer points of biodiesel

Though he doesn’t expect to instigate a one-man

insurrection against petroleum fuel, Holliday says his

project has piqued the interest of friends and family.

“Everyone loves it; they think it’s funny,”

he explains.

His father, he says, got a big kick out of sending Holliday

five gallons of turkey-soiled vegetable oil from Ohio

to Durango.

“He laughed.”

More laughable, Holliday says, is4

his frequent trips to the grocery store to buy panty

hose. He uses them to strain the food particles from the

used cooking oil he gets from local restaurants.

“I guess it’s kind of funny to see me standing

in line at Albertsons holding a bunch of panty hose,”

he laughs.

Does he prefer a color?

“Yeah, I like black,” he deadpans.

Those who don’t laugh, though, are skeptical, convinced

that using oil as gas really won’t work. Or that

if it does, once-powerful truck engines will only sputter

around town at the sluggish pace of someone who ate too

many of the donuts fried in that very grease.

Because there aren’t any biodiesel pumps in Durango,

Holliday still must rely on petroleum. His truck has two

gas tanks: One filled with petroleum; the other with recycled

vegetable oil. To heat the oil, Holliday first starts

the truck with diesel fuel and runs on that for about

five minutes. Meanwhile, the heater in the vegetable oil

tank warms it, making it viscous enough to work through

the engine. When it’s warm, he switches to that

tank, which he drives on primarily. Once he stops driving,

Holliday switches back to the diesel fuel, using it to

clean the gas lines so the oil doesn’t solidify.

In spite of the routine, Holliday isn’t concerned

that he has set himself up for a series of irremediable

mechanical problems.

Thunstrom is right by his side doing the fine-tuning.

For him, Holliday’s ambition also may offer him

a business windfall. Now that he’s converted an

engine, Thunstrom is confident he can assemble his own

kit from parts available in town, and then cut the labor

time from two days to eight hours.

As American as you can get

Holliday says he has contacted local oil companies about

procuring and selling biodiesel at the gas stations. He

said he hasn’t heard any promises, but he’s

been greeted with open-minded people who said they would

consider it. Meanwhile, Holliday says his next challenge

is educating locals. He wants to start giving presentations

at schools and community events. He acknowledges that

changing peoples’ mind, especially in our petro-centric

society, will be the chief struggle.

Because of the strong agricultural industry in this area,

there are several people who drive diesel trucks, Holliday

says politics often preclude any promise of changing fuel-buying

habits. He adds that it’s especially hard because

of the current administration.

“We have an oil tycoon for a president, who has

made his money on Texas oil,” Holliday laments.

Instead of the country’s leaders spending “$100

million” on the current situation in Iraq, Holliday

said he promotes a plan that would spend that money on

home soil to support the automotive industry to convert

cars to run on biodiesel.

“That could completely change our country from

being dependent on foreign oil to depending on ourselves

for our gas.”

The Colorado-based National Renewal Energy Laboratory’s

diesel projects claims that biodiesel could contribute

5 percent of this country’s diesel needs. That would

subtract 146 million barrels of imported crude oil each

year, it adds. Ultimately, this would diversify the energy

supply in this country, as well as reduce trade deficit

and improve the U.S. economy.

“Running a car on vegetable oil is as American

and as redneck as you can get,” says Holliday. “To

get farmers to grow our fuel, though, would be a revolution.”

Ultimately, Holliday concedes that it all comes down

to money. Like him, he wishes the government would sanction

and invest in alternative fuel. It reminds, him, he says,

of something a high school teacher once told him: “Every

environmental problem is just an economic problem in disguise.”

Holliday’s truck isn’t disguised though.

You can pick him out by the crunched back bumper and the

french fry smell wafting through the air.

|