|

From riding in to cemmentating on the

Tour de France, Bobke comes full circle

by Amy Maestas

|

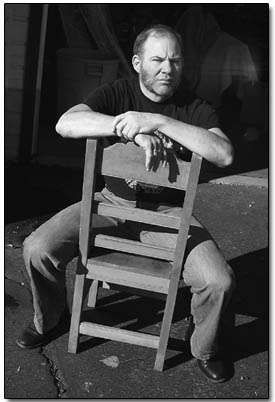

Bob Roll takes a seat

outside his garage in Durango. The cycling legend

has parlayed his knowledge of the sport into a career

as an unconventional

but beloved commentator for the Outdoor Life Network./Photo

by Todd Newcomer.

|

At this point in Bob Roll’s career, it’s

tough to discern if his fame comes from being a legendary

cyclist on the first American team to participate in the

Tour de France, or from his post-pro shaggy muttonchops,

inimitable commentating and random musings.

The former 7-Eleven team racer is popping up everywhere.

He has a regular stint as Tour de France commentator on

Outdoor Life Network. He travels throughout Europe to

announce other noteworthy cycling races. He makes appearances

at bike shows and other cycling events. He can also be

found somewhere, sometime, responding to reaction about

his newly re-released compilation of cycling columns.

And this, it should be noted, blows the truth out of

Roll’s declaration in his new book, Bobke II.

“As a pro cyclist, fame and fortune are soon forgotten,

but your suffering as a racer stays with you as long as

you live.”

Roll is riding on a wave of stardom. A mass of cycling

enthusiasts is buzzing about Bobke (Roll’s nickname)

and his ability to bring humor and wisdom to a sport that

still pales in popularity in the United States compared

to Europe. Subtitled The Continuing Misadventures of Bob

Roll, his book is an entertaining read about his life

as a bike racer – on road and trail – with

a healthy dose of sarcasm, irreverence and unorthodox

perspectives. The compilation was originally published

eight years ago, but the re-release has been updated with

ramblings that are more recent. Roll has added hilarious

cycling predictions for this century (including a guess

that Lance Armstrong would retire in 2001 and start a

band that featured local ex-cross country racer Ruthie

Matthes on vocals). There is also a new chapter reminiscing

about Roll’s two-week training stint with Armstrong

in 1998, when the current Tour de France champ was on

the road to recovery and an unprecedented cycling comeback.

These days, the muttonchops are as thick as ever. Yet

amidst all of the fame, he remains unpretentious and humble,

preferring to be in front of a camera than on a bike.

“I’ve ridden a half-a-million miles all around

the world,” he says. “I’m done with

it. I have filled up my vessel of suffering.”

That is not to say Roll has sworn off riding all together.

Like he wrote, his suffering during his bike career remains

with him. But you won’t find him leading the pace

line on the Durango Wheel Club’s classic Tuesday

night rides. Or even throwing down the gauntlet on a local

downhill course. Instead, Roll says these days when he’s

in town, he prefers “tooling” around the valley

solo at a comfortable pace (which is probably still twice

as fast as most).

“Sure, there is some residual power from racing,

and I might be faster than others, but speed is relative.”

‘Young and stupid’

So is a successful cycling career. Roll started cycling

in 1981 in Northern California, his home territory. There

is no grand story that accompanies Roll’s initial

interest in cycling. As he puts it, he was just a “young

and stupid kid” in his late teens who liked to ride.

But, after only two years of riding, Roll moved to Belgium,

where he participated in Europe’s premiere races

with the top echelon of the sport. And in another two

years, Roll became a professional.

It came early in his career – atypically early.

But as fans and spectators learned, Roll is anything but

a typical guy.

“That was pretty quick to turn pro,” Roll

recalls. “Most racers have a solid five or six years

as an elite amateur racer. I skipped all that.”

Roll admits that his rapid rise to professionalism created

problems.

“Tactically, you have no idea what’s going

on. The Europeans don’t like that.”

He was, after all, riding with an elite class of cyclists

who had participated in the sport for decades and carried

around the prestige and tradition. Since these riders

usually dominated the peloton, they had garnered the most

respect.

In 1985, corporate convenience store giant 7-Eleven sponsored

the first American professional cycling team. The team’s

first race was the 28-day Giro d’Italia. Roll and

his teammates were entering new territory, where foreigners

perceived them as “gifted interlopers, racing in

Europe for cash and kicks.”

The thrill is not gone

If that’s how they were perceived, it was one rough

way to go about it, says Roll. The 1985 Giro was a true

European fete for Roll since he was more accustomed to

100km races instead of 250km.

“Initially it was quite a race,” he says.

“It was so long that the last 10 days I honestly

didn’t know if I could finish it. I had an adequate

base of4 endurance miles, but I still spent more hours

in the red of suffering.”

The Giro was only a prologue to Roll’s suffering.

Seven-Eleven expected the race to be a launching pad for

the first ever American team participation in the 1986

Tour de France.

“It was just viciously hard,” says Roll about

the Tour. “There was more media attention and fan

frenzy than I ever dealt with. There was also so much

pressure and pandemonium.”

Seven-Eleven also had high expectations of the riders,

hoping at least one of the 10 would win a stage. It happened,

when Davis Phinney broke away from the pack and

|

Roll surrounded by cycling

memorabilia in his garage./

Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

dashed across the stage line. To boot, the team gave

more than a stage win. Team rider Alex Steida (from Canada)

grabbed the coveted yellow jersey after a morning stage

race. Though he lost it in a Team Time Trial later that

day, he put the American team squarely on the cycling

map.

“It was really quite thrilling,” says Roll.

Roll finished the Tour in 63rd place. He then went on

to three more Tours de France – in 1987, 1988 and

1990, though he did not finish in ’87 and ’88

due to gastrointestinal problems and a crash, respectively.

Extending the American spirit

Roll continued road racing professionally until 1992,

when he clipped out of his skinny-tire rig and planted

himself firmly on two knobbies to become a professional

mountain biker.

“By this time I was 30 years old and I had accomplished

most of the things on the road that I thought I was capable

of.”

For the next seven years, he excelled at the sport that

he calls “an extension of the American spirit.”

Ultimately, Roll didn’t spend a lot of time on the

podium, just like in his career in road racing. But he

is counted among the elite riders of his time and is as

well known as his teammates – whether for riding

among the pack, sharing gut-busting stories in his signature

way or burning an image in peoples’ minds when famous

cycling photographer Graham Watson snapped him riding

off pavement and through muck during the 1988 Paris-Roubaix.

Pot of gold

At the end of his racing career, which came in 1999,

Roll was ready for retirement from any type of riding.

“After 15 years as a professional, you don’t

have an ounce of lactic acid in your muscles, and you’ve

got nothing but wooden legs. It gets to be pretty monotonous,

so at that point I wanted to go. I didn’t know what

was next but I didn’t even care if I was a short-order

cook at McDonalds.”

Roll also saw the timing as fortuitous, opening the door

for a new generation of riders. For him, it was a sort

of passing of the guard to riders like Armstrong. It was

especially meaningful for Roll since he and Armstrong

eventually forged a close friendship, based partly on

similar beginnings. Like Roll, Armstrong spent little

time as an elite amateur. Consequently, Roll explains,

Armstrong also struggled with bike tactics and keeping

up with European standards. Clearly, Armstrong learned

quickly.

Roll ended his racing career just as Armstrong was coming

back from a battle with cancer. Today, Roll is one of

the people Armstrong credits for his return to cycling.

“Training with Lance the year of his comeback while

I was finishing my career really was the pot of gold at

the end of the rainbow,” he says.

‘Tour day France’

After retirement, Roll transitioned into the role of

commentator, creating a new image of himself – one

who could provide first-hand knowledge of the sport while

cracking up those listening to him.

As a commentator, Roll comes off a bit like Davis Phinney

with attitude. He has the ability to explain the sport

to armchair cyclists. To him, this is important, he says,

because there is still a chasm of knowledge between participants

and nonparticipants.

“To some, it looks like a bunch of guys riding

through a beautiful landscape, on their way to a picnic.”

Roll also has developed a self-effacing style of commentating.

He’s known as the outspoken commentator with a unique

fingertip-to-fingertip wrist roll while he’s talking.

He is also known for his now-purposeful pronunciation

of the Tour de France as Tour day France. In fact, during

this year’s Tour de France, OLN ran promotional

spots of Roll working on his pronunciation. Those much-talked-about

spots joined hilarious promos of Roll imitating other

flamboyant sports commentators, including Phil Liggett,

John Madden and Howard Cosell.

Even with all of the poking fun, Roll says his transition

into a commentator was a bit of a struggle.

“When you are an athlete, you are pretty much left

alone to ply your trade,” he explains. “But

when you are a commentator, everyone wants to tell you

how to do your job. You get the full brunt of peoples’

expectations and criticisms. I was ill-equipped to deal

with that.”

Ultimately, his love for the sport – as a spectator

– overshadows the criticism. He gets just as excited

watching the Tour de France as he did riding it. More

than anything, though, Roll relishes being part of a historic

event that is now, more than ever, gaining notoriety on

his home soil. Cycling to him is a dramatic sport that

creates incredible stories of human suffering and triumph.

The Tour de France is the pinnacle of it all.

“It’s so great because it’s an epic

struggle between a man, his teammates and 21 other teams,

all against a backdrop of nature.”

|