|

Crew films "Connecticut Kid"

at Vallecito ranch

by Jen Reeder

|

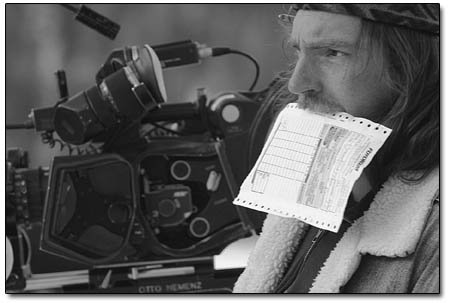

| 1st Assistant Cameraman

Nick Neino watches the actors on set as he prepares

for the next take./Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

The ground is covered with snow at a working ranch in

Vallecito. Several film cameras are directed at a corral,

where horses and actors mill around, waiting for someone

to yell “Action!”

The moment approaches.

“Everybody stand by...everybody quiet please...”

Just then, as if on cue, a horse farts and begins a mighty

bowel movement.

It was Dec. 12, a few days before wrapping on the set

of “The Connecticut Kid,” an independent film

eight years in the making – well, eight years of

looking for financing, at any rate.

|

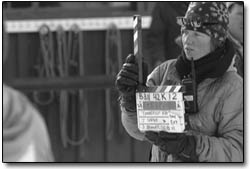

| Kitta Larsen prepares to document

a scene and snap the slate shut during shooting Friday

at Wilderness Trails Ranch./Photo by Todd Newcomer |

The film is based on the experiences of writer/director/star

Jack Serino, who worked at the Wilderness Trails Ranch

– where the movie was filmed – for a summer

when he was 20 years old. In the film, Serino, now in

his early thirties, plays a city slicker from Connecticut

who gets a hard time from the ranch hands but eventually

“saves the day and wrangles the horses when they

start running around,” according to a crew member.

“Don’t let him tell you it’s a true

story,” says Lance Roberts, an owner of the ranch,

with a sideways glance.

Because of the film’s tight budget, Roberts and

many crew members were drafted to act in the film.

“Everybody’s doing four jobs – it’s

a pretty small crew,” said Michael Black, 2nd unit

director of photography. “It’s funny because

most of the crew is acting as well. They’re doing

a good job, but it leaves us short on crew for some scenes.”

Crew members’ dedication is evidenced by the long

hours and cuts in pay they took in making the film. For

most, working on the film is a favor to Serino, who works

in the Los Angeles film industry as an art director. The

cast and crew members are coworkers and friends, and his

best friend, Jim Rosenthal, is producing it.

|

Art Director Gyll Huff snaps a Polaroid

of an actor’s costume so it can be accurately

duplicated in later scenes./Photo

by Todd Newcomer. |

Rosenthal said he first read the script eight years ago

and has wanted to make the film ever since. He was producing

a film in Salt Lake City, where he often works despite

living in LA, when he got the long-awaited call from Serino.

“Jack called and said, ‘I think we found

the money,’” Rosenthal said. “I called

all our friends and said, ‘Come help us out –

this has been Jack’s dream forever.’”

The friends came through, and the first meeting for

the film took place Thanksgiving Day at Denny’s

in Durango. Just a few weeks later, the film was in full

swing.

Today, after setting up a shot, Serino changes hats

– falling off a horse onto a pile of mattresses.

He stays on the ground even after someone yells, “Cut!”

“Jack, are you alright?” People start yelling.

“Is it your shoulder? Jack?”

He pops up and grins.“Was that good?” he

teases.

But the crew has reason for concern: The one major mishap

of the film occurred when Serino “took a big header

off a horse and the horse just wouldn’t stop,”

Rosenthal recounts. “I’m not sure if Jack

would want that mentioned.”

But then he calls over a red-headed woman and announces,

“She’s the one who saved Jack!”

The redhead is Amanda Williamson, a Vallecito local

who has worked at Wilderness Trails Ranch for seven years.

The crew met her at Virginia’s – where it

hangs out every night – and promptly cast her.

“They needed a wrangler named Red, and here I

am!” she laughs as she throws her hands in the air.

Incidentally, her dog “Rowdy” also was cast

in the film, though his stage name is “Killer.”

|

A camera sits unmanned as the crew

prepares the set for the next scene. /Photo

by Todd Newcomer. |

Rosenthal says that half the crew is staying in cabins

at Virginia’s, likes the restaurant’s food

and is especially fond of the pay phone, since cell phones

don’t work at Wilderness Trails Ranch. “At

the end of work we go to Virginia’s, and we all

fight for the pay phone, our link to civilization,”

he says.

And the business is great for Virginia’s Steak

House.

“It gives a little economic boost – we’re

glad to have them,” says owner Steve Dudley. “They’re

all young or middle-aged and have a lot of energy.You

can tell they’re working their buns off.”

And apparently they are – Rosenthal says the crew

works from 6 a.m. to 7 p.m. each day, and has had only

one day off in 14 days of filming. Everyone – aside

from production assistants, the indentured servants of

the film industry – is paid the same amount each

day: $100, approximately four times less than normal.

“I just promise them three meals a day and lots

of beer,” Rosenthal says fondly.

And aside from a couple of trucks getting stuck in the

snow, and “city kids getting horse bites,”

filming has been relatively smooth and the friendships

are intact, Rosenthal says.

“We all sort of grew up together in the film business,”

he says. And they have high hopes for what he describes

as “a wholesome little family movie about a guy

living out his dreams.”

|