|

Hilltop House helps offenders transition back

into the community

story and photos by Ole Bye

|

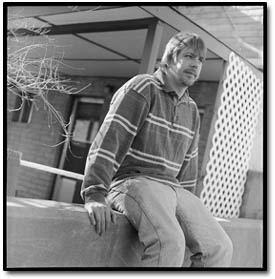

Mike Uhland sits in front of

his new apartment. He just moved out of Hilltop’s residential

program. “It’s

weird for me, just because I’ve never been sober,”

Uhland says. “I’m just trying to adjust to living

a more

socially acceptable lifestyle, I guess. It’s kind of

scary.”/Photo by Ole Bye. |

From its elevated position just west of the Animas River, Hilltop

House affords a perfect view of the city of Durango. It is into

this community that about 40 Hilltop clients bike or walk daily.

They go to jobs, to therapy, sometimes to coffee shops or to laundromats.

On the street, it is far from obvious that they are convicts working

their way out of the correctional system, people trying to regain

a place in society.

As a part of the Colorado Division of Criminal Justice, Hilltop

House plays the important role of halfway house, providing a buffer

between prison and the street. Hilltop Director John Schmier elaborates,

saying, "Community corrections was started to help offenders

transition back into the community by building a savings account

and helping them pay their restitution, court costs, fines but

also to provide them with a place where they can continue their

treatment."

According to Schmier, the Hilltop program is effective. "I

would say were in the mid-80th percentile of successful completions",

he says.

A number of clients agree, noting that the program helped them

get back on their feet and stay straight. "I hate to say

it, but, yeah, it has (helped)", says client Mike Uhland."Its

hard, but it's not as hard as the life I was living before".

But the road to re-assimilation is a long one, and former convicts

often encounter frustration, mistrust and alienation.

|

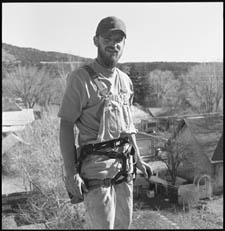

Hilltop resident Jed Bailey pauses during

his work as a roofer in Durango. “If it

did happen to come up in the future,” he says of his

time at Hilltop, “(I) hope that

things would be looked at through perceptive eyes.”/Photo

by Ole Bye. |

A look inside Hilltop House

The Hilltop program began in the early 1980s, and in the early

years, it shuffled locations between several downtown houses.

Funding was sporadic, says Schmier. "The budget was so small

that when they ran out of money, the facility would just close".

By 1985, funding had solidified, and the program built its own

facility on Avenida del Sol.

Direct-sentence offenders (who avoid prison by being sentenced

directly to Hilltop by a judge) as well as inmates from local

prisons always have been part of the program. In 1997, Hilltop

also began accepting inmates from the Colorado State Department

of Corrections and the Federal Bureau of Prisons. Funding for

Hilltop comes from all of these sources; the money follows the

offenders.

Clients of Hilltop participate in a tightly structured program

meant to reintroduce them to everyday life. To participate in

the program, clients must work full time but may substitute hours

with school. Merit is earned in a classification system, and clients

work toward nonresidential status, and eventually, release.

Schedules are precisely regimented, and clients must get passes

to leave the facility for purposes other than work or treatment.

Hilltop employees must be able to reach a given client within

two hours or the client is placed on escaped status. Breathalyzer

tests are a part of daily life at Hilltop, and residential clients

must be in-house for a minimum of eight hours a day.

"I pretty much supervise their whole life for the time

they're with us", says Case Manager Nick Beveridge.

When an individual enters the program, he or she is given 10

business days to find employment. "Usually, we have so many

people calling us looking for people to work, that we have a two-week

limit", says Schmier. "If you can't find a job in 10

days, we have to start wondering if you're employable...In the

nine years I've been here, I've seen one client go back to prison

because he couldn't find a job."

It's not difficult for Hilltop clients to find at least some

kind of work, in part because employers know what to expect. "One

thing employers like about us is the clients will show up, theyre

going to show up sober, and they're going to show up with their

lunch", Schmier says. Some employers are wary of liaison

with Hilltop, though, because of procedural requirements imposed

by the state, as well as conflicts with the tight schedules imposed

by Hilltop.

|

| Counselor Peg Christian leads

a discussion during the victim awareness class she teaches

at Hilltop./Photo by Ole Bye |

The day to day

By outward appearances, the life of a Hilltop client looks pretty

ordinary. The difference is that personal choice has been eliminated.

Client Jed Bailey comments, "A lot of times I may have called

in and said, 'Hey, I'm just not coming in today'. But at Hilltop

you cant do that. No matter what, you gotta go to work."

Although clients must work at least 35 hours a week, most work

more. Mike Uhland substitutes some of his work hours with classes

at Pueblo Community Colleges Durango extension. Having just moved

out of Hilltop House to his own apartment, he worries about making

ends meet: "I'm going to have to get a second job to swing

it", he says. "Thirty hours a week isnt going to cut

it."

Living expenses can be high, but a second primary financial

obligation of Hilltop clients is paying off their restitution.

"That's the biggest thing that is on my plate," says

client Serenity Leonard.

When they're not at work, clients can, depending on their status,

get social passes, allowing them to spend time doing other things,

like going to the coffee shop or the rec center. Where clients

can go is limited by the need to contact them within two hours.

"One of the main things that bothers me is you can't really

go hiking, you can't go fishing, you can't do anything where there

isn't a phone that they can get a hold of you," Uhland says.

|

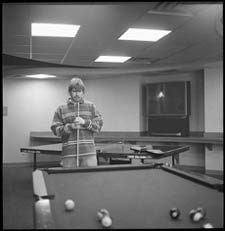

| Mike Uhland shoots pool at the

Durango Rec Center. The center is the only venue in town where

Hilltop clients can shoot pool because it is alcoholfree. |

Challenges

Adapting to the regimen of the Hilltop program is the first

challenge for clients; the next is confronting the stigma of being

a convict. "It was hard at first," Leonard says. "I

kept my head down. I didnt really go out and do things. But that

went away", she says, "as full-time work forced me to

be back in the public eye." Occasionally, some clients run

into employers who shy away from hiring them based on their past.

Bailey advises, "You have to look past a lot of what other

people think and feel, and build some sort of level of trust with

the community again." Although, he says for the most part,

Durango has been receptive and helpful.

On top of everything else, Leonard experienced difficulty as

one of only four women living in-residence at Hilltop House. "A

lot of the guys were just coming directly out of prison",

she says. "It was really hard. There were a lot of incidents

where the guys would make comments to me". Now that she's

in the nonresidential program, with an apartment of her own, Leonard

feels a different kind of pressure. "I have my freedom, but

I don't", she says."I dont live (at Hilltop), but I

have to follow their rules. I still have to call, and I still

have to let them know what I'm doing, and I still have a curfew."

Leonard, Uhland and Bailey are all natives of Durango and have

the advantage of knowing the turf. Clients who offended here but

are not natives often times have no connections in the community.

Peg Christian, who leads a victim awareness class at Hilltop,

points out, "These folks are really isolated from the community.

They go and work, but they dont know too many people. Re-assimilation

could be enhanced", she says, "by getting people together

in informal settings so they feel more connected the community."

"Because that's where you prevent crime, is when people

are connected because they dont want to hurt people they care

for."

The paramount challenge inherent in the Hilltop program is the

underlying foundation of strict personal responsibility. Self-restraint

is important, says Uhland, and when discipline gets frustrating,

the key is "just kind of biting your tongue." Uhland,

who has been out on probation before, says he has a hard time

leaving the structure of the Hilltop program: "I did all

right for a while, but then I got bored. I wasn't busy. I started

hanging out where I used to, and it was only a matter of time

before I was just as bad off as I ever was."

Many in the program have a hard time accepting its authority.

"They kind of treat you like a little kid, but then I try

to look at it like I've only demonstrated me being a little kid

to them, so how else would they treat me?" Uhland says. "It

is hard to always own up to that, you know."

The future

One thing that seems to be on the minds of Hilltop clients is

what they'll do when they finish the program. Some will stay in

the community. Jed Bailey is thinking about starting his own business.

"This will always be my home", he says, noting that

|

Serenity Leonard. Of the Hilltop program,

she says, “You either sink or you

swim. I chose to swim.” |

first, he is going to take a long camping trip. Mike Uhland doesn't

think he can be a part of Durango anymore, saying, "I kind

of feel like that's a cop out, that if I'm going to be sober,

I should be able to do it here, as well. But I can't help but

think it's going to be easier elsewhere." He adds, "Ultimately,

Id like to be a Ducati mechanic."

Serenity Leonard isn't sure if she'll still call Durango home,

but in the meantime, she has become involved in the La Plata Youth

program and visits classrooms to tell about her experiences in

the correctional system. "It's really rewarding", she

says, "we give back to the kids, and try to teach them through

our mistakes."

When asked about the effectiveness of the program, these clients

agree that you get out of it what you put in. "You either

sink or you swim. I chose to swim", Leonard says.

Bailey is pragmatic in his attitude, saying, "I messed

up, and I gotta do what I gotta do."

This feeling of accomplishment is equally important for Hilltop

employees, says case manager Kurt Wood. "When you have somebody

who is really open to the change in their life and you walk hand-in-hand

with them through the program, and you support their growth, and

you see them leave through the front door without handcuffs on,

its a really good feeling", he says. "Thats what kind

of recharges my batteries to continue to do this."

Still with three years to go in the Hilltop program, Leonard

is looking forward to the future. "I'm such a different person

than the person I used to be, so I'm ready to make changes in

my life."

|