|

San Juan Mountain Mustard Co. cranks

out grass roots condiments

written by Rachel

Turiel

|

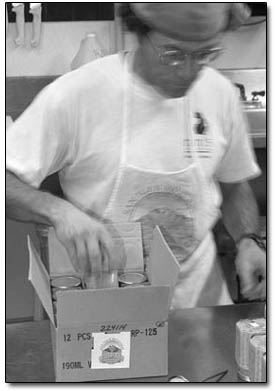

| San Juan Mustard Co. CEO and head

packer Paul Rappaport loads up a batch of his honey-dill

flavored Sweetwater Draw mustard. Rappaport bases

his mustards off a recipe from his New York grandmother./Photo

by Todd Newcomer |

It began almost 40 years ago in Brooklyn

with Grandma Louise’s mustard stash. Young Paul

Rappaport knew the pantry was filled with Grandma’s

special homemade blend of spicy, pungent mustard. One

night, Grandma, catching Paul reaching for the jar of

gritty, brown treasure, told her grandson “mustard

doesn’t go with our dinner tonight honey.”

To which a small but strong -willed Rappaport answered,

“It goes with my dinner.” And so a seed was

planted.

Although the San Juan Mountain Mustard Co. is just 1-year-old

this holiday season, Paul Rappaport (aka Colonel Mustard)

has been making mustard for more than two decades. Lonesome

for Grandma’s home cooking, he mixed his first batch

in college based on his mentor’s recipe. Due to

popular demand amongst his friends, Rappaport began making

a gallon at a time, spreading the joy throughout a small

community in Vermont.

Being outdoorsy, athletic and community minded, it’s

no surprise that Paul Rappaport would meet his future

wife, Stacie, in Vermont on a two-day, 150-mile bike ride

to raise money for multiple sclerosis. Redheaded Stacie,

co-proprietor and co-epicurean (as their business card

states), is busy. She talks fast, moves fast and is the

kind of person who knits, does yoga, gardens, skis, bikes,

and paints and landscapes her house and yard to perfection.

In 1992, the Rappaports had the opportunity to caretake

a farm in Vermont. With 40 gallons of maple syrup harvested

each year, and a garden full of horseradish root, Paul

and Stacie did the obvious: They made maple horseradish

mustard. Under the name “Green Mountain Mustard,”

with much respect and gratitude for Grandma Louise, they

launched their first mustard business.

Paul and Stacie laugh at their Green Mountain days: hand-written

labels Xeroxed and hand cut, sometimes with the list of

ingredients partially cut off in paper-cutter blunders.

The kitchen on their goat and cow farm was hardly certified

commercial, but they sold enough mustard to get to Alaska,

where they spent some time before their whirlwind travels

of the next four years to Oregon, Antarctica, New Zealand

and finally Durango in 1997.

It’s the mountains

Why Durango? Because of the mountains. Why mustard? Because

of the mountains. After years of teaching science and

working as a geologist in the oil and gas field, Paul

found a connection between what is undeniably good (mustard)

and what inspires him (mountains). While snowshoeing one

day in the Red Mountain area – the seeds of San

Juan Mountain Mustard already incubating in the minds

of the Rappaports – the couple was struck with the

direct connection between mustard and mountains: 1) If

they could work hard for a stretch, cranking out large

amounts of quality mustard, they’d have more time

to spend in the mountains; 2) San Juan Mountain Mustard

can help preserve their spectacular mountain home by donating

a percentage of its profits to local environmental groups.

That day on Red Mountain inspired the names of the five

original flavors offered by the mustard company. The bittersweet

maple-horseradish mustard reminded them of the bittersweet

boom and bust days of the early miners, and thus “Mad

Miners” maple-horseradish was born. A percentage

of the profits of Mad Miners Mustard goes to the Mountain

Studies Institute in Silverton, an organization that promotes

education and preservation of local ecology. The name

Cascade Creek, which was given to a creamy, Asian-style

spread, conjures up visions of snow cascading down mountainsides,

and thus proceeds of this mustard go to the Colorado Avalanche

Information Center, also in Silverton. “I call the

Avalanche Hotline every morning in winter,” Paul

says. “They’ve saved my butt many times.”

Tough town, sweet mustard

Durango’s a tough town, some say, but the Rappaports

have found nothing but support and encouragement for their

new venture. Paul, being the Colonel, makes all the mustard,

while Stacie, when she has a free moment from her

|

| Rappaport mixes up an

industrial-sized batch of his honey-dill flavored

mustard in Nini’s kitchen./Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

practice as a physical therapist and massage therapist,

does everything else. For their first year, with a staff

of two, things have gone extremely well. The managers

of Nini’s Taqueria, whom Stacie plays ice hockey

with, let them rent out their commercial kitchen for production.

Several business owners 4

in town allow the Rappaports to ship ingredients and

supplies on their trucks for no charge. Lady Falconburgh’s

has replaced all their previous table mustard with SJM

mustard; Nature’s Oasis carries their Sweetwater

Draw (honey-dill) in bulk; and their five flavors can

be found at 26 different establishments in Durango.

What makes this mustard so special? It’s made locally,

in small batches, by humans. The only power tool used

is a blender. The sweeteners – molasses, maple syrup

and honey – are unique and add flavor not found

in the typical commercial, white-sugar mustards. It’s

made with all natural ingredients, no preservatives. You

can even buy it in bulk, eliminating the need for another

plastic, disposable package.

“Some of these things make it cost more.”

Paul Rappaport shrugs. “I could make a $1.50 yellow

mustard if I wanted to.”

“Mustard ain’t supposed to be yellow,”

Stacie says, frowning.

Indeed. If your mustard is bright yellow, it has been

colored with turmeric, a naturally yellow spice.

Fire on Red Mountain

Nini’s Taqueria, Sunday morning, 25F degrees outside:

Paul’s in the kitchen with mustard seeds. Neil Young

croons about shooting his baby on the CD player. Paul

winces as he stirs four gallons of molasses chipotle mustard,

also known as Fire on Red Mountain. The sting of vinegar

and spicy smoked jalapeF1os waft into his eyes. Brown

and yellow mustard seeds are swirled with dried, green

herbs and bright red peppers as each stroke of Paul’s

hand marries the ingredients further.

The Rappaports rent Nini’s kitchen by the hour.

Though never hurried, Paul calmly and methodically navigates

the task of making 8 gallons of mustard in four hours.

Each step is ticked off on a checklist. Stainless steel

tools, lined up on the table like surgical implements,

glint off the florescent lights. Molasses and vinegar

are measured out ahead of time, waiting for the precise

moment when they will be added to the mix.

Though this work is culinary chemistry, the process is

simple and low tech. The bottling equipment was rigged

from pieces at the hardware store – its main mechanism

is gravity. Between stirs on the large pot of mustard,

Paul replaces Neil Young with a Beatles classic. And when

a just-filled mustard jar overflows slightly, he is quick

and easy with a paper towel.

After some time, Stacie bursts in from the frigid November

morning and smiles at the neat rows of bottles filled

with ochre-colored mustard flecked with green and red

confetti. She rolls up her sleeves and sets in on the

sink of dishes. As Stacie washes and Paul places empty

glass jars under the ever-flowing mustard spout, they

share their vision for the future.

Ski more, work less

The Rappaports would like to get more ski resort contracts.

They’re already at Durango Mountain Resort, Vail,

Taos, Telluride and Wolf Creek. For Vail and Taos, they’ve

created a private label, featuring the name of the respective

local ski mountain, and will donate a percentage of profits

to an environmental cause specific to each area. “Wolfie

and Telluride don’t get private labels, they’re

in the San Juans,” Stacie explains.

They would also like to ski more. Or simply have more

time to get out into the mountains. “I never even

got into ‘tele-shape’ last winter,”

Stacie laments. In addition to making the mustard, there

are always bottles to label, orders to fill, phone calls

to return, deliveries to make. This is on top of Stacie’s

physical therapy work and the Spanish classes Paul teaches

at the high school.

“It’d be nice to hire someone to do the labeling,”

Paul muses. “It’s fair to say I have other

interests besides making mustard.”

The levelheaded Rappaports are not afraid to dream. They

see the potential in owning their own commercial kitchen

and being able to create jobs in Durango at their mustard

plant. Paul would like to see bicycle-powered blenders,

Stacie would like to work two days a week and spend the

other five in the San Juan Mountains.

Meanwhile, in an apartment in Brooklyn, Grandma Louise

continues to make her own spicy sauce, knowing all too

well the moral of this story: Pay attention to your grandmas,

they have wisdom we can all benefit from.

|