|

River runner group seeks end to motor rigs, permit

system

by Missy Votel

|

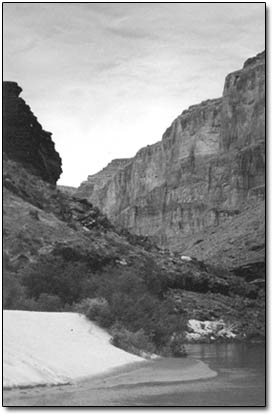

The sun sets behind the cliffs

overlooking one of the many sandy beaches along the Colorado

River in the Grand Canyon. The National Park Service is currently

revamping the Colorado River Management Plan, the document

that governs use along the river in the canyon. One private

boater group is calling for increased public access, wilderness

designation and an end to motorized

craft./Photo by Missy Votel. |

More than 130 years ago, John Welsey Powell led nine men down

the uncharted waters of the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon

– a trip so treacherous that three expedition members hiked

out rather than face the river’s wrath. And while Powell

may have had trouble recruiting volunteers, today there are more

than enough to go around.

At last count, there were some 8,200 people waiting to secure

a private launch date, and according to the National Park Service,

newcomers can expect to wait about 20 years for their number to

come up.

And while some see the quarter-century wait as just a law of

supply and demand, one group has dedicated itself to changing

the permit allocation system, one which they say favors commercial

outfitters and the rich while degrading the corridor’s wilderness

qualities.

According to Tom Martin, co-founder of River Runners for Wilderness,

a Flagstaff-based nonprofit group dedicated to obtaining wilderness

status for Grand Canyon National Park and overhauling the permit

system, a typical guided commercial trip costs more than six times

that of a private trip.

“It costs between $275 and $325 a day on a commercial trip,

versus an average of $45 a day for a private trip,” he said.

Speaking to the exclusive nature of commercial trips, he added:

“Half of the passengers on commercial trips make up the

top 12 percent of the country’s earners.”

Take a number

For the remaining percentage, the option is to take a number

and wait, he said. However, under the National Park Service permit

system, only one-third of all river-user days are allocated to

private river runners, with two-thirds going to the commercial

outfitters.

And this is what rankles Martin and members of his group.

“The waiting list is so long, those at the bottom of the

list will wait an incredible 20 years,” he said. “The

vast majority of permits go out to commercial concessionaires,

and the boating public is left behind with no reasonable access.

What is at stake is public access to the greatest river trip in

the world.”

According to Martin, who worked as a commercial river guide for

several years and has authored Grand Canyon guide books, the goal

of his group is not to do away with commercial trips but to ensure

“fair and equitable wilderness access.” Martin acknowledges

that wilderness designation would likely mean an end to motor

rigs in the canyon. However, he thinks banning motors is a “no

brainer” when it comes to preserving a natural wonder like

the Grand Canyon.

“There’s only one Colorado River and Grand Canyon,”

he said. “There’s nothing like it in the world.”

And while the prospect of prohibiting motor rigs may be wildly

unpopular among commercial outfitters, Martin said he thinks it

will barely make a ripple among the river-running public.

“Studies have proven that the public, when given an option,

prefer oar trips over motorized ones,” he said. “Nobody

is saying motor trips are better.”

As far as the permitting process goes, Martin’s group is

proposing one that would “front load” the system,

whereby people would secure permits and then decide from there

whether they would like to hire a company to guide them or do

it themselves.

“It would follow the demand of the public, permit for permit,”

he said, adding that a similar system is in place – and

successful – in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness

in northern Minnesota.

And with the Colorado River Management Plan – the document

governing use of the river through the Grand Canyon – up

for revisal, now is the time for river runners to unite, according

to Martin.

“We’re canvassing the country,” he said, adding

that Colorado has the highest number of people on the private

launch waiting list. “We’re trying to drive home the

message and get people to write their congressmen and participate

in the management plan.”

More

ways to get a Grand fix... More

ways to get a Grand fix...

Tim Martin, author of Day Hikes

From the River: A Guide to 100 Hikes from Camps on the Colorado

River in Grand Canyon and founder of River Runners for Wilderness,

will present a free slideshow and Grand Canyon management

plan update on Sunday, Nov. 30, at 6:30 p.m. at the Abbey

Theatre.

The slideshow will be followed by an 8:30 p.m. screening

of “The Same River Twice,” an award-winning

documentary that revisits a group of Grand Canyon river

guides 20 years after a pivotal monthlong trip down the

canyon.

The film, by Rob Moss, follows a free-spirited group of

friends and lovers on a month-long trip down the Colorado

River. Cutting between footage of their youthful, often

naked, unscheduled lives and the complex realities of their

adulthood today, the film creates a compelling portrait

of cultural metamorphosis. From running rapids to running

for mayor, “The Same River Twice” is a story

of change, choices and finding one’s place in the

world.

The event is sponsored by River Runners for Wilderness,

Weminuche Chapter of the Sierra Club, Taxpayers for the

Animas, and the Abbey Theatre. For more information call

385-1711.

|

In defense of motors

At least one river-user group doesn’t see eye to eye with

River Runners for Wilderness. The Grand Canyon River Outfitters

Association, which is made up of 16 commercial companies running

trips in the canyon, does see a need to protect the Grand Canyon

and find an end to the controversy, but it takes issue with some

of Martin’s goals.

For starters, the group would like to see wilderness designation

for the Grand Canyon with the exception of the river corridor,

which it sees as a main access route to the backcountry. Furthermore,

the group asserts that motor rigs do not adversely impact the

environment.

“Motorized use is transitory in nature and does not harm

or negatively impact the resources,” the group states on

its web site. If the practice was harmful, it argues, then it

would have become apparent over the last 50 years of motorized

use. However, wilderness advocates maintain that the corridor

is suitable for wilderness, which can only mean “motorized

use has not diminished 85 wilderness character.”

The outfitter’s group also turns Martin’s access

argument on its head, pointing out that three out of four commercial

passengers depend upon motorized craft for their trips.

“Such motorized access is essential in order to provide

the current level of public access,” the group states, adding

that a ban on motorized craft could drastically decrease public

availability of commercial trips.

“The number of passengers able to take these trips could

be reduced from 19,000 to as little as 8,000 or 9,000 annually,”

the group writes.

The outfitters association also points to its environmental stewardship

record as a defense. According to the group, five years ago, members

began changing over from two-stroke engines to cleaner and quieter

four-stroke engines. The group also has launched a research project,

with the intent of eventually developing an electric, zero-emissions

motor. 4

As far as permits go, the outfitter association advocates a “Real

People/Real Trip Dates” system whereby private boaters reserve

a specific date for a specific number of people and specific number

of days. The group predicts that the reservation system, which

is based on travel industry practices, coupled with an increase

in allocations, could produce an average wait for a private trip

of 12 to 20 months.

“A reservations-based management model offers great promise

to provide access to the Grand Canyon river experience for the

self-guided river trip participant on par with what professionally

outfitted patrons currently enjoy,” the group states.

Changing the system

And while both sides of the motor rig issue argue their cases,

the National Park Service will have the final say in the matter.

According to Linda Jalbert, recreation wilderness planner at

Grand Canyon National Park, the management plan is still in the

environmental impact study phase.

“We are currently working on the impact analysis of alternatives

as required by (the National Enivironmental Protection Act),”

she said.

A scoping period to gauge public opinion on the new management

plan was held last summer, including public meetings in Denver,

Flagstaff and Salt Lake City. The resulting draft EIS is expected

by early next year, which will be followed by another comment

period and more public meetings. The final EIS will be released

at the end of 2004.

“The draft EIS is a critical step,” she said. “That

is where we go to the public and look for public comment.”

Although Jalbert couldn’t specify what alternatives are

being discussed for the management plan, she did say that the

Parks Service is analyzing lower-use alternatives as well as a

non-motorized alternative and a “do-nothing” alternative,

as required by law. She said that last summer’s scoping

process netted more than 50,000 comments from more than 15,000

people. And while the comments were all over the board, she said

there was consensus on the failure of the permit system.

“The general feeling was that we need to change the system,

it’s pretty unpopular,” she said. “We just don’t

know what we’re going to change it to.”

And while parties on both sides of the issue await the final

decision, they expressed optimism over the ability to reach an

amicable resolution.

“Those who have been down the river realize the comradeship

among the groups, often helping one another if need be,”

the outfitters association wrote. “Yet in addressing the

allocation issue and the issue of access for private boaters,

we all must appreciate that the NPS must manage 85 in the overall

public interest.”

Likewise, Martin, with River Runners for Wilderness, expressed

hope in finding common ground and improving the contentious situation.

“We are problem solvers,” he said. “Given half

a chance, we can do way better.”

|