|

Writer and activist Mary Sojourner

to pay a visit to Durango

by Amy Maestas

|

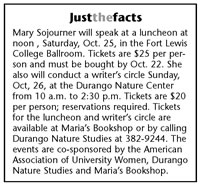

| Writer and environmental

activist Mary Sojourner will be in Durango this weekend

to address a luncheon and conduct a writer’s

workshop./Courtesy photo. |

Mary Sojourner refuses to fly. Although

flying is faster and sometimes cheaper, Sojourner insists

on traveling by train. But it is not because she’s

an aviophobe. Instead, she can’t stomach how much

flying disconnects her from the earth.

A Flagstaff, Ariz., writer and environmental activist,

Sojourner’s quirk truly characterizers her deep

connection to the land, which is the central theme of

her work. Without the land, her existence – and

influence – in the West would be tentative at best.

That Sojourner landed in the West by default deepens

that relationship and raises the value of her presence.

Growing up in the small farming town of Irondequoit, N.Y.,

Sojourner – a name she took in 1972 because of her

admiration for women’s  suffragist

Sojourner Truth – had an early yet different relationship

with nature. When her parents set her off alone in a canoe

on an Adirondack mountain lake, Sojourner found respite

from a sometimes bleak childhood. Her mother, she writes

in an essay titled “First Meeting,” suffered

severe depression, undergoing stints in psychiatric hospitals

and shock treatment. As Sojourner says, it was a distressing

disease to have in the 1940s and 1950s because people

were diagnosed as “hysterical, narcissistic, manipulative.”

Her mother survived every suicide attempt. suffragist

Sojourner Truth – had an early yet different relationship

with nature. When her parents set her off alone in a canoe

on an Adirondack mountain lake, Sojourner found respite

from a sometimes bleak childhood. Her mother, she writes

in an essay titled “First Meeting,” suffered

severe depression, undergoing stints in psychiatric hospitals

and shock treatment. As Sojourner says, it was a distressing

disease to have in the 1940s and 1950s because people

were diagnosed as “hysterical, narcissistic, manipulative.”

Her mother survived every suicide attempt.

So, when she paddled away, under the aurora borealis,

Sojourner sowed the seeds of her connection with nature.

The scene meshed with her passion for cowboy movies. Only

nearly 40 years later did she recognize how powerfully

these experiences shaped her life.

Red rock amusement

In her early adult life, Sojourner reared three of her

four children alone in Rochester, N.Y. It is a city so

dreary, Sojourner explains, that it intensified her own

depression. She struggled to put bread on the table while

working on women’s mental health issues. In 1982,

a friend invited Sojourner to visit the West. She declined.

“I said, ‘No way. It’s nothing but

Disneyland with red rocks,’” she says. “At

the time I was just too rooted in East Coast urban culture.”

Sojourner eventually relented. The first stop was the

Grand Canyon. Her friend prompted her to the edge of an

overlook.

“I felt as though every cell in my body was rearranged.

That’s how powerful it was.”

She returned three years later. She was alone this time,

and purposely visited Flagstaff to seek a copy of Edward

Abbey’s Monkey Wrench Gang. She found his book –

and others – which she read while traveling on a

train home to the East Coast. After arriving, Sojourner

hastily packed her home and pointed her Pontiac Firebird

and U-Haul trailer West.

Honker SUVs

In Flagstaff, Sojourner, a short and irreverent woman

who is now 63, immediately began writing – a task

she had always wanted in life but was too busy taking

care of others to pursue. She also quickly became active

in environmental causes, which she writes about in her

novel Sisters of the Dream, a collection of short stories

called Delicate, and essays in Bonelight: Ruin and Grace

in the New Southwest. A regular contributor to High Country

News and National Public Radio, Sojourner has earned recognition

as a sharp-witted environmentalist who pens passionate

essays about the bastardization of the West’s open

spaces. Like many others, she sees developers running

roughshod over a delicate landscape that can never be

reclaimed. Golf courses and gated communities drive her

to the point of rage.

Sojourner is known for her extensive opposition to the

Canyon Mine, which a Denver-based company proposed to

open on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon to extract uranium.

She and other members of the activist group Earth First!

were arrested and jailed during one protest. Since then,

she’s devoted her efforts to defeating many more

private and public developments. As most can guess, she

endures the scourge of many developers and property-rights

owners. Like so many others in the West, she is caught

in a perpetually divisive battle among those who want

to protect the land and those who want to engulf it.

Through writing, Sojourner says she’s tried to

form a bond with people who believe differently about

the environment. It disappoints her that she has had little

success. She took advantage of her days spent working

in Flagstaff’s Aradia bookstore, where she often

interacted with tourists who were scarcely educated about

land preservation.

“I’ve tried again and again to communicate

with them,” she explains. “But they usually

just climb back in their honker SUV’s and drive

off.”

‘Apathists of the West, unite!’

Still a relative newcomer to the West, Sojourner does

not deny her own impact here. She uses her writing and

activism to awaken people to how much power they have

to minimize the marks they leave behind.

“There is no way to live anywhere without having

any impact,” Sojourner says. “I own that.

But I work hard to soften that impact.”

In fact, Sojourner goes to great lengths. She refuses

to patronize corporate retail stores. She lives in a two-room

cabin in the forest, with a wood stove but no indoor plumbing.

Is this extreme? Yes, she admits, though she doesn’t

expect everyone to live or fight like her.

In an essay titled “Apathists of the West, Unite!”,

Sojourner backs that up.

She writes: “In fact, as an American living in

the inter-mountain West, it is impossible to be purely

activist. To live in 100 percent alignment with awareness

of the devastation of the planet would be, as Stephen

Lyons has suggested, to wander quietly off, die in a nontoxic

manner and hope to feed more innocent creatures.”

Still, nary a reader escapes the essay without a mark

on his or her conscience. She doesn’t give readers

any wiggle roomto defend their actions, whether it’s

trying to explain why they paid $200 for hiking boots

or why, as she writes, they don’t long for the return

of the guillotine after watching a television ad for Range

Rovers shot against the backdrop of red rock.

If readers are guilty of either of these things –

and a slew of others she lists – they are apathists.

Apathy, she eludes, is what will kill the West. And when

you are apathetic, you are disconnected from the land.

Sojourner willingly discloses that she battles her own

demons in living a life that is incongruent with her beliefs.

For the past several years, she has battled an addiction

to gambling. While she spent hundreds of hours working

as a self-proclaimed “hardcore environmentalist,”

she spent nearly as many in a Las Vegas casino betting

up to $800 a month. The addiction was so powerful, Sojourner

nearly lost sight of her purpose.

“This summer it became clear to me that it was

going to eat my brain cells and keep me from writing,”

she admits. “It’s nice now to be congruent

with my beliefs, even though I got a lot of stories from

those experiences.”

She is now recovering in an outpatient program.

Breaking hearts

“Our very racy, technified times have seduced people

into forgetting about connection,” says Sojourner.

As a writer and teacher, she strives to reconnect people

to land – whether it’s the backcountry or

a city park. When she arrives in Durango next week, Sojourner

will conduct one of her well-known writing circles at

the Durango Nature Center to coach interested writers

in reconnecting. She believes that story is more than

just linking words; it is also about opening the senses

to natural surroundings that often get sucked into the

undercurrent of everyday living. But when people are able

to see how their stories fit into a certain place, they

are able to write about their existence with integrity.

Often, it takes drastic measures to achieve this, she

adds. That’s why her activism is so integral to

her writing. It involves consequence, which often acts

as a motivator.

“To have that connection to place it often means

we have to break peoples’ hearts and light a fire

under their asses, because only then can you let things

in and out of your heart.”

|