|

Lorax Forest Care takes a gentler

approach to logging

written by Ole Bye

|

| Chris Vandeleur drives

his draft horses Fanny and Dan past a log deck on

the Timberdale Ranch subdivision near Bayfield. The

Belgian- Percheron crosses are brother and sister

and weigh 2,000 pounds each./Photo by Ole Bye |

Care is not a sentiment typically associated

with logging. But the employees of Lorax Forest Care seem

to genuinely care about their work, and it shows in all

facets of the operation, from the marking of fated trees

to the final sawmill cuts. But the great embodiment of

this care is in the draft horses used to drag felled trees

out of the woods. Horses are the environmentally sensitive

backbone for a modern philosophy of logging practiced

by Lorax owner Eric Husted and his crew. Husted’s

hope is “to try and change people’s perceptions

from logging to forest restoration, to look at it as a

service that’s going to enhance the value of their

property, rather than a way to make money off the land.”

|

| A detail of a part of

the harness called the collar, which bears the weight

of the horse’s pull./Photo by Ole Bye |

The relatively minor impact left by Lorax and its horses

leads employee Chris Vandeleur to echo these sentiments:

“We’re not just working and making a buck

85 we’re making a little bit of the whole better.”

The Bayfield-based crew thins forests on private land

with the main purpose of protecting rural homes from wildfire.

But fire mitigation isn’t the only consideration

people make when hiring Lorax. Many are combining fire-fuels

reduction with a desire to maintain forest health. Residents

of Timberdale Ranch, near Bayfield where Lorax is now

at work, decided that low-impact logging was the right

path to good forest stewardship. Resident Doug Maxwell

says, “Initially my concern was the fire danger.

And the bonus is that we get to restore the forest to

a healthy, natural condition.”

|

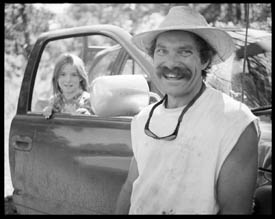

| Lorax owner Eric Husted and daughter

Kyla./Photo by Ole Bye |

The work

On a typical day, one might not even notice the Lorax

crew at work. Only the distant whine of chainsaws betrays

the intense labor of Lorax employees Luis Ramos and Luis

Arellanes. The pair is usually well ahead of the horses,

felling trees on distant properties while the team follows

behind, bringing logs to the roadside.

Felling trees is far from easy. Ramos and Arellanes first

evaluate marked trees and predict where they can be dropped

to benefit the horses. Brush must then be cleared from

around their bases, and any snags that might impede the

fall must be removed. Eventually, the tree is cut and

all of its branches are removed. This “slash”

is piled to one side leaving a clear path for the horses

to remove the log.

Although men are doing some of the hardest work, the

horses remain the stars. Husted concedes, “(People)

come and all they want to do is take pictures of the horses.”

Coming upon the team working in the woods feels a bit

magical, as if one is looking into another age. From a

distance, the horses seem to move smoothly and naturally

through the woods. But up close, the ground shakes as

they pound past, hot breath rasping through dilated nostrils,

with Chris Vandeleur in tow.

Vandeleur pauses tensely in the otherwise constant motion

of his work, a leather rein held firmly in each hand.

At his fingertips are the combined 4,000 pounds of Dan

and Fanny, brother and sister Belgian-Percheron crosses.

The horses shift and stomp, eager to pull, despite the

heat and dust. Their heavy leather harnesses creak and

sing with a metallic jangle. “Wait for me,”

Vandeleur warns crossly as Fanny shows signs of jumping

the gun. Then he says in an even, conversational tone,

“OK, let’s walk.”

The team explodes into motion, nearly cantering as they

thunder out of the stand of ponderosas with a 30-foot

log in tow. Vandeleur careens after them, hopping back

and forth across the skidding, bouncing log, attempting

to keep slack reins while not being crushed. In a few

seconds they reach the edge of a field and pull alongside

other logs in a “deck” formation, where Vandeleur

halts to unfasten the log chain. Then all three return

to the woods to repeat the process.

Fanny and Dan seem to enjoy the logging, and so does

Vandeleur. He says of the work, “It might be the

best I’ve ever done. (It) keeps me in shape for

hunting season.”

That’s no wonder, considering the miles he runs

following his charges. An apparent vein of fun runs through

the work, along with a vein of concern. Husted says that

he wouldn’t be in logging without the horses. “Yeah,”

he replied. ”They’re the main incentive. They’re

the best part!”

|

Vandeleur leaps across

two tumbling

logs as he races to keep up with the

team./Photo by Ole Bye |

Getting down to business

Being fun and eco-friendly are not the only traits that

make the horses valuable to Lorax. They also keep Husted

from having to advertise. “They sell themselves,”

he says. “A lot of the people who hire us, hire

us just because the horses are involved.” The premise

works well. Husted is booked for the next two years and

has increased his work force from just a couple employees

to six. He has four horses to choose from when making

up teams and is raising a fifth.

A fairly new addition to the business has been a small,

mobile sawmill, operated by two people, which is used

to cut rough lumber. In the future, Husted plans to open

a woodworking shop as a further extension of the process.

But he’s cautious about capitalizing on his easy

source of timber: “I don’t buy any of the

material unless I’ve already got it sold,”

he says. “All that stuff we’re milling down

there is from pre-existing orders. The standard logging

thing where you buy standing trees and cut them down and

try and make money is just bad forestry. Because really

the only way you can make money is if you go in and take

the nicest biggest trees and get out as fast as possible,

with no mitigation.”

Lorax’s profits come mostly from the fees landowners

pay to have their forests managed. Husted says that selling

logs doesn’t pay the bills when using horses. “I

tried that for the first year and a half,” he says.

“If you do really high volume and work 80-hour weeks,

you might be able to make a living that way, but it would

be hard.”

Still, Lorax’s niche is a valuable one, according

to Husted. People are willing to pay more for a better,

more environmentally sound job. And people also are willing

to pay for the ideals espoused by the company.

“We’d be better off doing more things with

a lighter hand than always bringing in big guns, big technology,

big power,” Husted says. “You can accomplish

the same things with a much lighter touch.”

Lighter touch also makes for smaller overhead. “I

started with two horses for about 3,000 bucks, and a chain

saw, and a trailer and a truck,” Husted says. “So

you can get into business way cheaper with horses than

you can with heavy equipment.”

One paradox of the Lorax operation, however, is the use

of an outside contractor’s mulching tractor to chop

up ladder fuels after the horses have removed the logs.

The result is a low-fuel, nutrient-rich forest floor,

which is ready to sprout grass. Except for the mulch,

you might not know a tractor had been in the woods, because

if there is impact, it isn’t visible.

“We don’t really need giant bulldozers and

stuff for most of this work. But then I’m not opposed

to... (the) chipping unit. It does exactly what we want.

It lays stuff down on the ground and makes it fire safe,”

says Husted.

As for the future, Husted is optimistic. At a pace of

1 to 2 acres a day, he has work in his current location

for months to come. “There are thousands of acres

that could use the same thing that we’re doing,”

he reports. “We’re supporting about five families

on three, 400 acres of timber a year. So you could support

dozens of little operations like this around here, and

people would make good money, and they’d get to

stay close to home.”

Making the Lorax choice

Although homeowners in the Four Corners area were marginally

interested in thinning trees on their property before

the summer of 2002, “There was a catalyzing event,

and it was called the Missionary Ridge Fire,” says

Joni Hedemark, a resident of Timberdale Ranch. Hedemark

was largely responsible for initiating the process

|

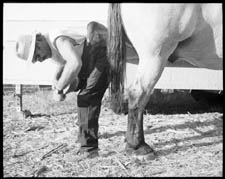

| Husted trims and files

Dan’s unshod hooves, which keeps them from chipping

or breaking./Photo by Ole Bye |

that led to hiring Lorax to do work at Timberdale Ranch.

When Hedemark learned of cost-share grants available from

the State of Colorado to aid in wildfire mitigation, she

tossed the idea to the Homeowners Association, and 80

percent of residents indicated they were willing to participate.

Homeowners began to educate themselves on what needed

to be done to protect their homes from fire. They brought

in Husted, who lives nearby, to give talks on forest management,

and a partnership was born.

But it wasn’t just neighborly goodwill that led

Timberdale Ranch to hire Lorax. Residents also admired

Husted’s ideals and methods. “Many of us liked

his approach to forest management – more of a common-sense

approach, if you will; nonaggressive and perhaps not typical

of what we would picture to be a logging approach,”

Hedemark says. And, of course, there’s the horses:

“We also liked that he utilized the horses, a tool

that was so common at the turn of the century.”

When thinning is completed to correct standards, Timberdale

residents will receive a $93,000 grant from the state.

To date, all properties in Timberdale that have been thinned

have passed inspection even though the Colorado State

Forest Service offers no incentive to encourage environmentally

sound logging practices.

Husted says that horses seem to be an ideal, if not sanctioned,

tool for thinning forests on private property around houses.

“I see the horses as an excellent tool for doing

just exactly what we’re doing – thinning in

areas that are populated and already roaded,” he

says.

The team can work in tighter spots, for example, around

houses than big machines can. Also, less impact appeals

to homeowners like Hedemark, who notes, “If (Eric)

were to skid logs on your property, depending on the situation,

in three to four weeks the skid trails are gone.”

|

| Luis Arellanes fells a tree./Photo

by Ole Bye |

Healing the forest

After Husted and crew pass through a forest, its face

is changed dramatically. Trees stand well apart from each

other, the forest floor is shorn of ladder fuels like

scrub oak, and sunlight fills the woods. Initially, it

looks too manicured to be natural, but Husted comments,

“That’s a little closer to the original components

of the ecosystem – bigger ponderosas and more grass.”

Fewer trees are now competing for water in the thinned

area, so they have a better chance of being healthier

and disease-resistant. “When trees start to get

bigger and closer together, and you throw in a drought,

the competition becomes even more keen,” says Kent

Grant of the Colorado State Forest Service.

Moving onto the next area of Timberdale to be thinned,

Husted marks trees to be cut and explains what he’s

looking for in the trees he’s cutting. “We’re

thinning for 15- to 30-foot spacing,” he says. “We’re

removing anything that looks unhealthy or weak.”

And then indicating a large ponderosa, he says, “Wow,

that’s a cool tree.”

Walking on, he suggests that the forest can be restored

to its natural, original state. “It’ll take

a hundred years, I’m sure. But yeah, I think it’s

doable,” he asserts, spraying another blue “x.”

A quarter mile below, the horses are working, but they

can’t be seen or heard.

|