|

A look at the life of the 24-hour

solo mountain bike racer

written by Missy Votel

|

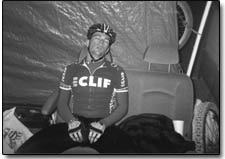

| Greg Vlaming, of Durango,

attacks the singletrack near Durango Mountain Resort

during the 100 MTB earlier this summer. A 24-hour

solo mountain bike racer, Vlaming placed 11th at the

2002 24 Hours of Moab race. He plans to compete again

this year./Photo by Todd Newcomer |

It’s not often that a mountain bike

racer falls asleep on his way to a second-place victory.

But after several hours in the saddle, that’s exactly

what Rick Wetherald, a recent Durango transplant from

Florida, did. Actually, it was more of an out-of-body

experience, he’ll tell you – a closing of

the eyes while the body was in a state of reclining along

a horizontal plane. But it wasn’t “sleeping,”

he insists.

“I hit a little rock and forgot I was clipped in

and tipped over and just sort of laid there,” said

the 20-year-old Fort Lewis student who moved here with

the hopes of making the school’s elite mountain

biking team. “I just sort of forgot what I was doing.”

And while narcoleptic fits may not seem conducive to

a career in the amped-up sport of mountain bike racing,

according to Wetherald, it’s actually quite common

among the races he attends. But these are no ordinary

races; and Wetherald is no ordinary racer. He is among

a small but growing class of FCber athletes – the

24-hour solo racer.

Wetherald, fresh from a second place finish in his age

group at the 24 Hours of Adrenaline Solo World Championships

in British Columbia, is succinct in explaining why he

is drawn to a sport that pits man against nature, time,

darkness, the elements and, mostly, his own mental anguish.

“Whenever somebody says ‘This is the most

challenging thing,’ I say, ‘I want to do it,’”

he said “I like challenging myself.”

And apparently, Wetherald, who has completed three 24-hour

solo races, is not alone.

“It’s gotten real popular,” he said.

“The solo attendance at the Worlds doubled since

last year. Talk about a big gathering of nut cases.”

Sue Grandjean, a two-time solo finisher of the 24 Hours

of Moab race, prefers to think of herself and fellow solo

racers as fun-loving, soul riders.

“It’s getting back to the roots of mountain

biking,” she said. “There’s not a lot

of rules and regulations. It’s just so much fun.”

But, the 29-year-old, who recently returned to FLC to

get her teaching certificate, admits there is a little

twinge of competitiveness that comes into play.

“The first year I did it, I had people telling

me I couldn’t do it,” she said.

Grandjean, who tips the scales at a buck and change,

admits she was a little off the back as far as traditional

training methods went. However, the way she sees it, there’s

no reason to spend any more time in the saddle than is

necessary.

“If you’re going to be on your bike for 24

hours, you don’t want to be on your bike that much

beforehand,” she said. “People say you have

to train a lot, but you don’t want to burn out on

the bike.”

Besides, she pointed out, finishing such a race involves

as much, if not more, mental stamina than physical, something

that Greg Vlaming, another 24 Hours of Moab solo veteran,

wholeheartedly agrees with.

“The physical part is easier than the mental part,”

he said. “It’s definitely a mental strategy;

you have to break it down into doable chunks.”

|

Forbidden slumber: Rick Wetherald

catches a little shut-eye between laps at

the 24 Hours of Adrenaline Solo World Championships,

held last month in

British Columbia./Photo courtesy Rick Wetherald |

In addition to cold weather, saddle sores and muscle

fatigue, 24-hour racers must suffer through the sensory

deprivation and loneliness that comes with being out in

the middle of nowhere in the middle of the night. In fact,

those early morning hours can be eerily like a scene from

“Night of the Riding Dead,” Grandjean said.

“During the day, every other racer on the course

wants to talk to you because they see you’re solo,”

she said. “But come around 1 a.m., it’s total

silence.”

And that is when the madness sets in.

Vlaming, 39, who was Durango’s top male finisher

in the 24 Hours of Moab last year, admits that the combination

of a high-powered headlamp, motion and sleep deprivation

can play tricks on the mind.

“I totally hallucinated at night,” he said.

“All the rocks and bushes had shadows – I

saw animals.”

Appropriately, these darkest hours of the night often

coincide with the darkest, most trying hours for a 24-hour

racer.

Grandjean recounts an episode in one of her races when

it got so cold that other racers were trying to warm their

hands in front of their head lamps. It got so cold, in

fact, that she stopped drinking – a mistake she

would soon regret. Suffering from exhaustion, delirium

and dehydration, her head light ran out of batteries.

It was 4 a.m.

“I just sat there and waited for someone to come

by and then followed them to the finish,” she said.

“When I got back in, I told my support crew that

I quit.”

However, as any 24-hour racer will attest, behind every

rider is an even more determined support crew.

“We made an agreement that I’d go back out

when the sun came up,” said Grandjean. “So,

I hung out for a few hours and went back out.”

Wetherald said it is always tempting to find a reason

to drop out, but he is kept going by one big motivator:

his father, who also serves as his one-man pit crew.

“You know Jesse Ventura? That’s my dad,”

he said referring to his father’s resemblance to

the wrestler turned governor. “He’s what really

keeps me going.”

Vlaming also said he was tempted by the siren song of

sleep, only to be pulled from the depths of despair by

his pit boss, a former girlfriend.

“It was kind of comical,” he said. “I

came back in after a lap and said, ‘Maybe I’ll

just lay down for 10 minutes,’ and she said ‘The

hell you are.’”

And, as is always the case with any story of triumph,

it is always darkest before the dawn.

“When the sun comes up, it’s like a shot

of energy,” said Vlaming.

Which is not to say the riders don’t rely on other

forms of energy as well – ranging from Gu by the

bucketload to some more unconventional – if not

unappealing – power sources.

Vlaming said he relied on a steady diet of energy bars

as well as a secret stash of flat Coke and water when

the going got tough.

“I used it as a carrot to get me to the top of

some of the hard climbs,” he said. “I would

tell myself ‘If I make it up this, I can have a

drink when I get to the top.’ It was a real treat.”

Grandjean, who admitted she is not a big fan of prepackaged

energy bars, relied mostly on PB&Js and energy nuggets

from the bulk bin at Durango Natural Foods. She also divulged

her secret weapon: Slim Jims, which in addition to providing

protein and salt, are easily transportable and nearly

indestructible.

“I would hang onto it and eat while I rode,”

she said, adding that after a particularly nasty fall,

another racer had stooped to check on her well-being.

She stood up unscathed and proudly produced her Slim Jim,

which also had escaped harm

“I yelled up, ‘Got my Slim Jim,’”

she said. “I held onto it the whole way down.”

It is this ability to pick oneself up after a fall, dust

off the Slim Jim and get back in the saddle with a smile,

no matter how much it hurts, that makes or break a 24-hour

racer. In fact, while they may entertain thoughts of quitting,

it’s usually not even an option.

“I didn’t enter the race to quit,”

Vlaming said. “I just try to enjoy it in the moment.

It’s like eating an elephant: You gotta take it

one bite at a time.”

Besides, pain is fleeting, they say, but the taste of

victory, whether official of personal, is insatiable.

“After every race, I say, ‘No, I’m

never doing it again, and then a month later, I say I’ll

do it again because I know I can do better,” said

Grandjean, who is still debating whether to this years

24 Hours of Moab, which takes place mid-October. “I’ll

probably end up doing it. What the hell? I’ve got

all winter to recover.”

|