|

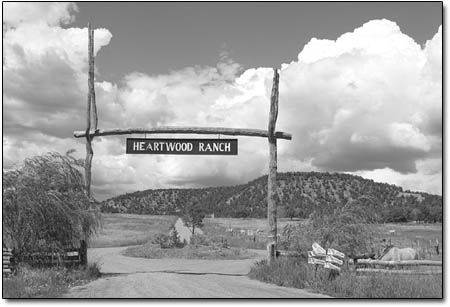

| Afternoon clouds roll past

the entrance to Heartwood Ranch recently. The Bayfield co-housing

subdivision is based on a Danish concept that focuses on

retaining open space and creating a small-scale neighborhood

where the placement and style of houses foster interaction

and cooperation among residents./Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

At Heartwood Cohousing, a private subdivision in Bayfield,

residents have turned the clock back 50 years to a time when

neighbors shared much more than property lines and speedy glances.

It used to be that subdivisions were actually designed with

neighbors in mind. Houses had front porches where residents

gathered, garages were built behind and unattached to houses,

residents actually saw each other come and go.

However, in the past 20 years, subdivisions have taken a turn

toward privacy. Garages face streets, protruding in front of

houses. Six-foot fences block any kind of interaction. And sometimes

the nearest neighbor is several acres away. Suddenly, people

are living in a disjointed community.

But residents of Heartwood Cohousing eschew such living arrangements,

which is why they have built a housing project that drastically

transforms the definition of community. Heartwood requires that

all houses have front porches. Homeowners don’t have fences

cordoning themselves off from their neighbors. There are no

garages either. And cars – not the central theme in this

community – are relegated to the periphery of the cluster

of houses, obligating everyone to walk along the common pathway

to get home.

Here, residents are creating a kind of micro-society that relishes

steady interaction, cooperation and collective living. To some,

iat appears to be a radical style of existence yet it only seems

radical in the context of recognizing how subdivisions are built

today, residents say. Actually, this style of living is about

as traditional as you can get.

“This isn’t some new wave of a living style,”

says Johann Robbins, a Heartwood resident of 2 BD years. “This

is closer to how we are wired to live versus having a garage

in front and using cars all the time.”

Danish movement

The cohousing idea began in the early 1970s in Denmark, when

dual-income professionals wanted better day care and safer neighborhoods.

Twenty-seven families in Copenhagen turned to cluster housing

and a pedestrian-friendly development style that fostered relationships

with neighbors.

In the late 1980s, the cohousing concept gained recognition

in the United States, and the first cohousing project in the

country was built in 1991. But only in recent years has it begun

to gain popularity.

According to the Cohousing Association of the United States,

there are 66 completed cohousing projects in this country –

a 12 percent average annual growth rate during the past five

years. The group reports that there are 19 neighborhoods under

construction and an estimated 150 cohousing groups in various

stages of the development process.

Colorado ranks third among the states with completed neighborhoods

(nine) and has three other active projects. When Heartwood Co-housing

completed its development in the winter of 2000, it became the

first cohousing project in the Four Corners. The nearest cohousing

project is in Santa Fe, N.M.

Typically, cohousing projects are designed and built by residents,

who work on a grassroots basis from beginning to end. The core

group secures financing – either public or private –

to purchase land and start construction. Residents decide on

all aspects of the development, including design, business structure,

policies and procedures. However, as cohousing has gained recognition,

some developers have created companies that do all of the cohousing

design and development.

Interaction and cooperation

Because Heartwood is the first cohousing project developed

in La Plata County, residents met some initial resistance from

the county government. Robbins says county leaders were reluctant

to allow a cluster of houses on a small tract of vast acreage.

Heartwood owns 350 acres, but the development, which consists

of 22 completed homes (all single family except for one duplex)

and two in progress, is confined to only 7 acres. It’s

not an affordable housing development, and home prices and values

at Heartwood range from between $220,000 to more than $400,000.

Restricting the amount of land used for housing was necessary

to accomplish the goals of cohousing, Robbins says. Those goals

are to retain open space and create a small-scale neighborhood

where the placement and style of houses foster interaction and

cooperation among residents.

The asphalt pathway weaves throughout the cluster, connecting

each home to others as well as a playground and outlying buildings.

Houses – all uniquely designed with adobe and solar power

– are well kept with an organic look and carefully xeriscaped

yards. The focal point of the development is the Common House.

Psychic energy

Upon entering Heartwood, the Common House is the first thing

residents and visitors encounter. It’s a large 3,700-foot

building where residents meet for anything public – meals,

meetings, recreation, parties and socializing. Besides an abstract

walkway, the Common House is what unifies the more than 40 residents

who make Heartwood their home.

On a recent Friday evening, a couple dozen children and adults

meet at the Common House for their weekly potluck. Before sitting

down to dinner, the adults hold hands while encircling the kitchen

island. This week, they are “christening” a newly

built wooden island where they can prepare food for the potluck

and the twice-weekly community dinners, which residents take

turns cooking.

|

| Sunflowers brighten the walkways

through the Heartwood Ranch subdivision. Built in 2000,

the cohousing neighborhood covers 7 acres and consists of

22 homes, with two more under construction./Photo by Todd

Newcomer. |

Keeping in the spirit of remembering the various ethnicities

and practices among the group, the adults don’t engage

in any kind of religious offering or blessing. Instead, they

praise the woodwork of the residents who built the island. And

they dictate the rules for using it – not to be heavy-handed

but to respect different cultures by keeping the island kosher.

During dinner, Michael and Beth Walker, who were involved with

Heartwood from its inception, explain why they decided to move

out of their Durango neighborhood and join this cohousing community.

Michael Walker says that the family yearned for a sense of

community and cooperation that was impossible to find in most

neighborhoods. They wanted a place where they and their children

felt safe, where neighbors cooperated and where they had a social

group with whom they shared common characteristics.

Even though they sought this type of association, the Walkers

wondered if cohousing would work for them – as well as

the others.

“It takes a lot of money and psychic energy to get something

like this built,” Michael Walker says. “And it calls

for a lot of heart to keep it together.”

Beth Walker says the concept works at Heartwood because residents

are loyal to the idea of living in unity.

“When you move into someplace like this, it’s no

longer ‘I,’ it’s ‘we,’”

says Beth Walker. “This type of community is a different

way of thinking.

Fran Hart, who actually lived in a trailer on the land before

the project began, agrees.

“I thought to myself, if Native Americans can live with

six generations in a Hogan, I can learn how to live next to

my neighbors,” she says.

Hart says she chose to live in a cohousing development because

“it’s lined up” with the values in her life

– notably clustered housing and open space.

Modeling maturity

Besides creating a sense of community within the larger society,

residents believe this style of living is a good role model

for children. The Walkers say their two children know how to

co-exist with others in a more cooperative way, using consensus

and communication as tools to ensure peace.

“Our children have blossomed in a thousand ways since

moving here,” Beth Walker says. “They are growing

up learning that they have to consider other people.”

Since cohousing’s foundation is built on consensus, harmony

and volunteerism, living in this type of environment teaches

many more lessons than how to run a neighborhood, residents

say. Ultimately, each person gains insight and knowledge that

run the gamut of life – from carpentry skills to interpersonal

communication. For that, they say, there is no equivalent in

most neighborhoods.

“I think that this is the longest, most valuable personal

growth experience you can have – at least that’s

what it’s been for me,” says Michael Walker.