|

Durango indie filmmakers play

by their own rules

written by Missy Votel

|

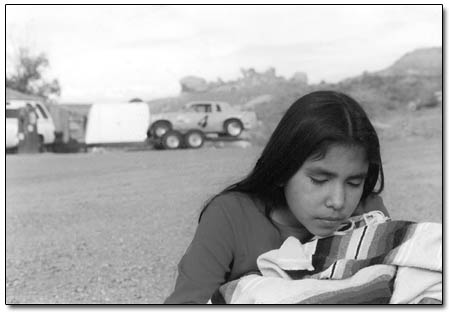

| 10-year-old Nicole Luna

in a scene from the recently released short independent

film “121 to Aztec,” written and directed

by local filmmaker David Eckenrode. The 32-minute

film was shot on location in McElmo Canyon and the

Moki Dugway, of southeastern Utah. /Photo courtesy

David Eckenrode |

The Four Corners area is no stranger to

Hollywood, its dramatic landscape serving as a backdrop

for everything from John Ford Westerns to fast food commercials.

Yet, when left to their own devices, one group of young

local filmmakers would just as soon leave the glitz and

glamour in the Golden State.

“We pretty much broke every rule of filmmaking,”

said David Eckenrode, a Durango native and independent

filmmaker who just wrapped production on his first film,

set in the desert country southwest of Durango. “We

camped out, slept in our trucks,” he said. “We

definitely didn’t do it Hollywood style. It was

kind of like an Outward Bound film set.”

Eckenrode, 33, along with fellow DHS classmate John Sheedy,

31, founded Ouzel Motion Pictures, a small film company,

this year. Eckenrode, who cut his teeth in  the

industry by working on various movie sets, writes and

directs while Sheedy shared writing responsibilities and

was the cinematographer. Together with the help of local

producer Rick Carlson, the small startup just released

“121 to Aztec,” a short about two stock car

drivers en route to a race who get sidetracked when they

help a Navajo girl on a quest to bury her dead dog. the

industry by working on various movie sets, writes and

directs while Sheedy shared writing responsibilities and

was the cinematographer. Together with the help of local

producer Rick Carlson, the small startup just released

“121 to Aztec,” a short about two stock car

drivers en route to a race who get sidetracked when they

help a Navajo girl on a quest to bury her dead dog.

On a shoestring budget of $8,500, the crew shot the film

in four days last October in McElmo Canyon and the Moki

Dugway in southeastern Utah. The film stars two professional

actors, Chad Afanador and Adam Bartley, who Eckenrode

met through the Creede Repertory Theater, as well as 10-year-old

Nicole Luna, who plays the part of the young girl. There

is even a cameo by local amateur actor Dan Groth, who

can be found serving up lattes by day.

Eckenrode, who wrote and directed the film, said he enticed

his mostly inexperienced crew by appealing to their more

basic needs as well as their passion for the art.

“I told them, ‘I can feed you and give you

beer,’” he said, adding that even the beer

was gratis, thanks to Ska Brewing.

Eckenrode said the filming was not without its pitfalls,

including long days on the set and unforeseen disasters.

“We blew out the transmission on the stock car on

day three,” he said. Pressed for time to wrap the

shoot, crew member Michael Farley, a race car driver from

Farmington, towed the car to Cortez where he wrenched

on it throughout the night and returned victorious the

following morning.

Eckenrode said it was this sort of camaraderie and unwavering

devotion that convinced him to pursue a more permanent

working relationship with the group.

“What was so neat was that here we had a blue collar

working man, a Navajo family, two actors from New York

City and a pack of freaks, and we all had a great time,”

he said of the crew and cast members. “It should

be a metaphor for how the world should be.”

Apparently, Eckenrode wasn’t the only one who felt

the chemistry.

“When we finished, Adam Bartley said, ‘You

know we have a really special group here; we should form

a company,’” Eckenrode recalled. “We’re

now just putting it into a legitimate form.”

|

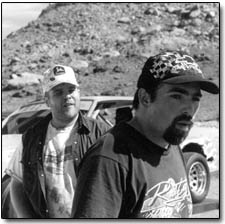

Adam Bartley, left, and Chad Afanador

in a scene from Ouzel Motion Pictures’

“121 to Aztec.” Both men are professional

actors with the Creede Repertory

Theatre who worked on the film last October. The project

went so well they are

planning to do more work with the Durango film company,

according to founder

David Eckenrode./Photo courtesy David Eckenrode. |

Eckenrode, who wrote “121 to Aztec” in the

spring of 2002 while temping at a desk job in San Francisco,

said after a private premier this week in Durango, he

hopes to take his film on the road. He is waiting to hear

from three film fests in Austin, Texas, as well as one

in Portland, Ore. Closer to home, he said he has plans

to submit the short to the Durango Film Festival as well

as the Aspen Short Film Festival.

In the meantime, Ouzel, which is Old English for a common

black bird, has already begun setting its sites on two

more projects: “The Commute,” a short written

by Sheedy about life on either side of the Mexican-American

border; and “Cyanide Black-Eyed Susan,” a

feature length murder mystery written by Eckenrode and

set in a mining community.

“It’s very poetic, almost like a visual poem,”

said Eckenrode of “The Commute.”

He said the film, which is about 12 minutes long, should

be complete in about three months. As for his feature

film, he would like to start shooting by the fall of 2005.

Although he wants to shoot in Silverton and Creede, he

said the theme of the film, which centers on two friends

trying to solve the mysterious mining death of a friend,

is one that is common to most small Colorado mountain

towns.

“It’s about letting go,” he said. “That

and the changing of the old guard, a scenario you see

in all of these Colorado towns.”

For Eckenrode, who studied biology at Evergreen College

in Olympia, Wash., before becoming interested in film,

the short films are more of a stepping stone to bigger

and better.

“This is just the tip of the iceberg, to learn

and get better at the craft,” he said. “We

don’t want to stick with these small shorts. We

feel we have a large pool of talent to draw from.”

And while he says he would like to keep the company based

out of Durango, Eckenrode, who currently plies his days

rowing rafts, admits working from a small town has its

drawbacks, namely the struggle to make contacts and stay

afloat.

“It’s hard here,” he said. “If

you want to make things happen, you’ve got to do

it yourself. If you sit around and wait for people to

give you your chance, you’re going to be doing just

that – sitting around.”

Nevertheless, he said there are some advantages to living

in this out-of-the-way corner of the world.

“Living in Durango enables us to tell stories that

are unique,” he said. To illustrate his point, he

referred to a recent film festival in New York City that

was attended by a friend. “He said all of the films

were about life in New York and that after a while, it

got old,” he said. “What we want to do is

bring light and a voice to people in those hidden corners.”

And while Eckenrode harbors dreams of hitting it big

like many small-time filmmakers, he says it won’t

be at the cost of his ideals.

“The main thing I’ve learned is to tell a

story,” he said. “So many people get lost

in what ‘the industry’ says you have to do,”

he said. “But for me, less is more. It leaves things

open for questioning.”

However, one thing that isn’t open for questioning

is Eckenrode and his company’s will to succeed.

“This is about art,” he said. “You

can teach technical, but you can’t teach heart and

soul. We just have something special. It’s a force

to be reckoned with.”

|