| Hell,

heroism and hallucinations in the Hardrock 100 race by Amy Maestas

|

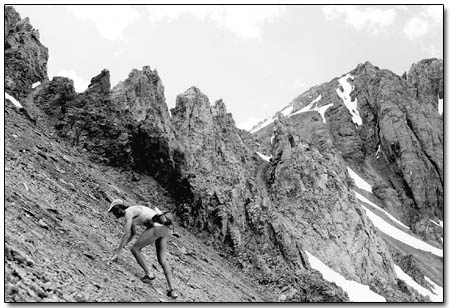

| Kirk Apt, the first-place

male finisher in 2000, negotiates a scree slope on

Grant-Swamp Pass on his way to victory./Photo courtesy

Dale Garland. |

Five years ago, Chris Nute ran 98 miles through the backcountry

of the San Juan Mountains. Awake for nearly two days,

Nute came to a final river crossing. He treaded the frosty

alpine water. When he made it to the other side of the

river, Nute knew it was the end. Not the end. The end

– if that were Nute’s fate – probably

would have come long before mile 98. Instead, this was

the end of the race. With only two miles left to go, Nute’s

mind and body switched gears. Physically, his body turned

to autopilot. Right leg in front of left leg. Breath in,

breath out. Heart beating steadily – puh pum, puh

pum, puh pum.

Nute’s mental capacity, however, was loosey-goosey.

The last river crossing was a mental break, he recalls.

He was out of danger now, so his brain relaxed. But before

his very eyes – literally – the scene changed

drastically. Nute began hallucinating. The scenery turned

to black and white. Colors – red, blue, green –

took off in different directions, separating like oil

and water, just like bad acid. Drugs be damned, Nute was

tripping all the way to the finish line.

Thirty-nine hours, 21 minutes and 33 seconds after he

started out – all colors intact – in Silverton,

Nute had completed his first 100-mile endurance run. It

was quite a feat for a backcountry runner who challenged

himself to the race because he had just turned 30 years

old.

This is the Hardrock Hundred Mile Endurance Run. While

there are at least 30 other 100-mile endurance runs in

the country, the Hardrock is, rightfully so, known as

the hardass of all races. More politely, it’s called

the “graduate’s 100-miler,” meaning

that it’s the race 100-milers should attempt only

after participating in the less-grueling endurance runs

like the Leadville 100, Rocky Raccoon (Hunstville, Texas),

and Western States 100 (Squaw Valley, Calif.). Most years,

only half the participants finish the race.

Many of these other 100-mile races have been around for

more than a decade, and many of them are far larger and

more popular than the Hardrock. But since its inception

in 1992, the Hardrock has poised itself as the toughest

backcountry challenge for the best-trained and conditioned

athletes.

Hardrock homage

When the Hardrock was conceived the intent was to somehow

connect the four Colorado mining towns of Telluride, Ouray,

Lake City and Silverton. The organizers also wanted a

gutsy event that would pay homage to the hundreds of hardrock

miners who made their livings for years chipping away

in the nearby mountains. Because the miners have always

been regarded as rough as 150-grit emery cloth, these

men knew that the race had to be equally harsh. It is.

The Hardrock begins in Silverton at 9,317 feet. After

a short jaunt on 1.3 miles of paved road, the run takes

off into backcountry terrain of 11 miles of dirt roads,

13 miles of cross-country singletrack and 76 miles of

jeep roads. The course rises 12,000 feet above sea level

seven times, 13,000 feet above level six times and summits

14,048-foot Handies Peak. The lowest point of the course

is 7,680 feet in Ouray. All told, there are 33,385 feet

of climbing and 33,385 feet of descending. Race promoter’s

translation: the Hardrock is like “running from

sea level to the top of Mt. Everest and back.” Except

at the Hardrock, there are no oxygen tanks, no North Face

sponsors and certainly no Tenzing Norgay.

To Everest and back

The story of how Nute became interested in backcountry

running is much like the stories of other Hardrock contenders,

including Silverton resident Emily Loman and Durango resident

Marc Witkes. All three also share this: none of them had

done any other 100-mile endurance runs before they participated

in Hardrock. Laymen’s translation: They picked the

hardest endurance run for their first racing attempt.

Consequently, all three had to petition the race committee

in order to be considered for entry. At the time, the

race policy stated that Hardrock participants had to complete

at least one of eight 100-mile runs on its requirements

list. This ensured race organizers that the participants

knew what they were getting into, along with proof of

their physical and mental moxie.

Nute, Loman and Witkes had the proof. Nute, now 35 and

the Outdoor Pursuits Coordinator at Fort Lewis College,

had been running small races and marathons since he was

a kid. Later, he stepped up running to the backcountry,

where he fell in with a group of avid ultra-marathoners

in Durango. Nute traveled with friends to the Grand Canyon,

where twice a year they do “double-crossings,”

running from the North Rim to the South Rim and back,

achieving 42 miles on foot. It quickly became his inspiration

for the Hardrock.

“It was right up my two alleys of trail running

and backcountry travel,” Nute says.

Then, in 1997 he caught a glimpse of the Hardrock’s

brutality, when he paced a friend participating in the

race.

“It was the straw that broke the camel’s

back,” he says. “I smelled the event that

year. Immediately, I knew I would do it the next year.”

Witkes’ and Loman’s stories mimic Nute’s.

The 36-year-old Witkes, an auditor, freelance writer

and retail salesperson, began running marathons in college.

When he moved to Durango, he, too, hooked up with the

trail-running group. Eventually, he stepped up marathon

running to backcountry running.

When Witkes talks about the Hardrock, he speaks with

unbridled enthusiasm. An admitted social wallflower, one

can tell that Witkes is so addicted to running that it

is, if not the heart of his world, at least its gallbladder.

“If I didn’t run, I wouldn’t have any

friends,” says the unabashed Witkes. “It’s

fun; it’s a rush.”

Loman, a 27-year-old law student at University of Colorado,

Boulder, had less experience as a runner. Once she made

friends with other endurance runners, it became her social

circle. Like Nute, Loman started making the spring and

fall trips to do double-crossings in the Grand Canyon.

Soon, she found herself cramming her weekends with long

runs.

“I couldn’t think of what else I could possibly

be doing,” Loman says. “I like being outdoors

and sightseeing. This just allows me to go a lot farther

a lot faster.”

Before her first Hardrock run in 1999, Loman had completed

four 50-mile ultra-marathons. Within nine months of becoming

an endurance runner, Loman was set to attack the Hardrock

course.

She completed the race in 45 hours – just three

hours under the 48-hour cutoff time. Being so close to

the course (Loman lived in Durango at the time), she was

able to run and study about 80 percent of that year’s

course. It was, she says, a boon to finishing the race

because she knew what to expect. She repeated her victory

in 2000, during which she cut her overall time by six

hours.

Agony of defeat

Just as three of these runners have tasted Hardrock victory

– literally, since participants are required to

kiss the rock at the Silverton finish line – all

also know the agony of defeat. Each of them has dropped

out of the race once.

|

| A runner and his pacer high-five

as they pass the old Buffalo Boy Mine above Silverton./Photo

courtesy Dale Garland. |

Nute’s second attempt in 2001 ended at mile 82

because he was suffering altitude sickness and exercise-induced

asthma. He tried to push through the attack, but the running

gods wouldn’t have it.

“It stunk. I felt healthy and had an easy 18 miles

to go. I had the energy, but the second I tried to run,

I couldn’t catch a breath,” Nute recalls.

For Nute, the race came to a bitter end. He made it another

five miles to an aid station to seek help. Because he

was at such a remote location, he had to wait to be rescued.

So there he waited with his thoughts of defeat –

legs ready to run and his mind as sharp as the blades

of the medical evacuation helicopter that plucked him

off the mountain.

That same year, Loman was back at the Hardrock hoping

for a three-peat. She conquered the first 50 miles, which

she says is a critical physical precursor to the second

half.

“Those miles are the fine line between pushing

yourself past your comfort zone but within that zone enough

that you don’t crash,” says Loman.

After defining that line, though, Loman hit the wall.

She began throwing up violently and continuously. She

presumed that she had eaten bad food somewhere along the

trail. There was no stopping the sickness – until

mile 60.

“I threw up the lining of my stomach,” Loman

says bluntly.

She offers details, though apologetically.

“The lining looked like veal cutlet, to be honest,”

she explains.

Loman surrendered to defeat. But she’s back –

possibly. She’s registered to run this year’s

race, though earlier this week she said she might have

to pull out due to an injury. It’s a letdown for

someone who loves the Hardrock run more than any other

100-miler.

“It satisfies me aesthetically more than the Leadville

run,” she says. “I like the variation of the

terrain. I also like the looped course and the atmosphere

among the runners. The Hardrock is really competitive,

but Leadville – at least the way I run it –

is more cutthroat.”

Humility at Handies

Witkes had to deal with defeat on his first attempt in

1998. It was harder to swallow than most defeats, he concedes.

Upon announcing to his friends that he planned to do the

Hardrock, they told him he likely wouldn’t succeed,

especially since it was his first 100-miler. He blew off

their comments with an inflated ego.

But by the time he hit the 30-mile mark, Witkes was eating

crow. He had extreme altitude sickness and would have

to brave Handies Peak in the dark. He, too, surrendered.

“I felt humiliated because I was so cocky about

doing it,” Witkes admits. “Here I was at mile

30 with my head between my knees. There was no one there

to save me on Handies Peak. I thought, ‘Geez, if

I go up any higher, my head is going to burst.’”

Witkes bowed out of the race that year. He returned in

2001 and finished, in spite of spraining his hamstring

at mile 96. He hobbled the last four miles holding his

leg, barely able to walk. He was selected to participate

in this year’s race, but three days after selection

he was injured and had to give up his spot. Instead, he’ll

pace his girlfriend, Cathy Tibbetts, of Farmington. He’ll

be back again, he promises.

The mountains win again

Nute says that no matter how hard Hardrock participants

explain to laypeople what compels them to run in the most

grueling, brutal, unforgiving races in the States –

a race where runners might see ornery elk, bear, mountain

lion or could fall hundreds of feet to their death with

one small misstep – they never succeed.

“The typical layperson just hears ‘100 miles,’”

Nute says. “They don’t understand the elevation

gain. So to some people, they just don’t get it

from the get go.”

Witkes tries to explain the insanity in a different way.

He says everyone should have something in his or her life

that offers inspiration and provides confidence. Success

in one endeavor helps success in another.

“It doesn’t matter what you have in your

life that inspires you,” he says. “People

should have something, even if it’s Tiddly Winks.”

Or the Hardrock Hundred Mile Endurance Run. After all,

these runners say, it’s about testing your own strength

– mentally, physically and emotionally. It’s

about personal goals and personal gains; it’s about

the spectacular scenery and solace. Winning is minor.

“You never really win against the mountains anyway,”

Witkes says. “The mountains always win.”

|