|

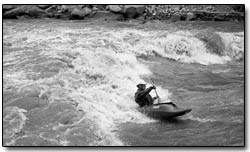

| A kayaker plays below Smelter

Rapid earlier this week. Two local men, Aaron Lombardo and

Forrest Jones, started a business to design whitewater parks

and river play features in towns throughout the country.

/Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

In the past several years,

one man’s name has become synonymous with whitewater parks

in Colorado: Gary Lacy. But that could soon change if a couple

of enterprising Durango men have a say.

Aaron Lombardo and Forrest Jones recently started Hydraulic

Design Group, the newest entrant in the rapidly expanding world

of whitewater parks. And armed with many years paddling experience

between them, they intend to give Lacy a run for his money.

“We saw the need for some alternative river parks,”

said Lombardo, adding that while Lacy’s designs are popular,

he has heard from several pro paddlers who are looking for more

out of the whitewater park experience. “What we want to

do is make world-class features that are up to standards to

facilitate world-class events.”

|

Lombardo stands with plans for a

Glenwood Springs whitewater park.

His company, Hydraulic Design Group,

competed against Gary Lacy to design

the project. /Photo by Missy Votel |

As an example, he points to Durango’s own crown jewel,

Smelter Rapid. The rapid, which has been tinkered with several

times over the years, is slated for work this fall under the

direction of a community task force made up of river users and

stakeholders.

“What Lacy typically does is take C- rivers and turn

them into C+,” said Lombardo. “But what we have

here is a B+ or A- river that we just may want to fix.”

Lombardo also said his desire to enter the field was born of

a need to help the environment.

“I want to make more play parks in cities so people don’t

have to travel long distances just to paddle and burn fossil

fuels,” he said.

Lombardo said he and Jones decided to join forces professionally

after working with other community members to build a play hole

downriver from Smelter in 2000.

“Basically, it was spurred from building Corner Pocket,”

he said.

The hole, which has withstood three years of run-off, has gained

a dedicated following among the local and national paddling

community, he said.

The City of Durango has replaced the

Boulder company hired to work on Smelter Rapid this fall,

opting instead to use local resources.

“Representatives from the local

river community requested that we take a different direction

and utilize the expertise we have locally and see if we

can come up with a design and work together on that,”

said Cathy Metz, Durango director of parks and recreation.

Last year, Gary Lacy, of Recreation Engineering

and Planning, was contracted by the city to make improvements

to whitewater features at Smelter. However, there was

opposition to his plan as well as the use of an outside

company to do the work.

“We decided not to pursue the services

of Gary Lacy and are going to pursue another method of

community involvement,” said Metz.

She said the city is forming a task force

of river users and stakeholders to steer the Smelter project.

The group will also be responsible for coming up with

a master river-use plan for work done beyond Smelter,

as required by the Army Corps of Engineers. Right now,

the city has identified 10 other sites on the Animas for

potential whitewater development.

Metz said the task force is still in

the process of forming, and no date has been set for its

first meeting.

“I imagine, if all goes well, we’ll

have our first meeting this month,” she said.

She said if the group reaches consensus,

work on Smelter Rapid could begin this fall.

“There’s a specific time

period set by the Army Corps of when we can do work,”

she said. “It would be early fall if we do go in.”

|

“World champion Eric Southwick said it was the best hole

in the 11-state area,” said Lombardo.

And while Jones and Lombardo scored a coup with Corner Pocket,

as local paddlers may know, they were not so lucky with work

that was performed on Smelter that same year. With the force

of the following spring’s run-off, a rock in the hole

shifted, creating a strong “keeper” hydraulic at

certain water levels.

Lombardo said that shifting rocks and mutating features go

with the territory, adding that two of Lacy’s recent projects

– one in Salida and one Steamboat Springs – met

similar fates. Without the use of grout, or cement, to hold

rocks in place, most manmade river features will require regular

maintenance, he said.

“Does the city build a park and then never come back

to water the grass? You have to have maintenance,” he

said.

Nevertheless, Lombardo said he and Jones learned a lesson in

humility from the Smelter experience, particularly how to reconcile

the desires of different user groups.

“We definitely learned a lot from that,” he said.

“Enough to know how to deal with communities and go about

it.”

And although grout often is the answer to avoiding such calamities,

it is not always the most popular one. As a result, Lombardo

said his company is trying to come up with alternatives.

“We are working on some different ideas other than grout,”

he said.

Lombardo is banking on innovation and a staff of experts and

consultants to make his company competitive with Lacy. Recently

Hydraulic Design Group brought Nick Turner, a civil/hydraulic

engineer and whitewater park designer from Bozeman, Mont., on

board.

“Nick has a whitewater park business and did a few projects,

and we basically joined forces to make one company,” Lombardo

said. “He can take our designs and run flow studies on

the computer to see how they’ll work.”

The company also uses local environmental consultant Sean Moore

to help with obtaining Army Corps permits and mapping, and employs

the help of professional freestyle boater Jimmy Blakely with

design.

Nevertheless, Lombardo notes that taking a bite out of Lacy’s

monopoly is a sort of chicken-and-egg scenario.

“Until we get our first job and prove ourselves, it’s

going to be tough to compete against him,” he said.

|

Local boater Luke Hanson plays in the

Corner Pocket wave earlier this year./Photo

courtesy Aaron Lombardo. |

In the meantime, Hydraulic Design has gotten its foot in the

door, Lombardo said, going head-to-head against Lacy for several

jobs, including one in Glenwood Springs (the outcome of which

has yet to be decided). The company also is creating a feature

later this year for the Colorado Timberline Academy north of

town and is working on feasibility studies for Telluride and

Rangely.

“We are working on conceptual design, cost analysis,

surveying the river bed and talking to community members about

what they’d like to see,” he said.

He also has offered up his company’s services to the

City of Durango for the Smelter work.

“I’ve offered my team’s expertise on a volunteer

basis to the city if needed,” he said. “It could

potentially save Durango $100,000, at least. We would be working

with people that represent each river user group on a task force

that’s going to answer to the city.”

And while they many never unseat Lacy as the king of Colorado

whitewater parks, Lombardo notes that the field is still relatively

new, and there’s plenty of room for newcomers.

“If Colorado is setting an example, play park growth

is going to explode,” he said. “There are 15 in

Colorado. Just imagine how many towns there are across the country

with rivers running through them.”