| A

day with Durango's cycle recycler written by Rachel

Turiel

|

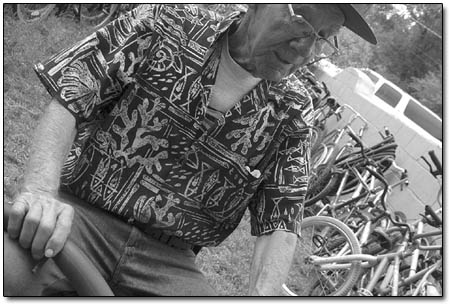

| Taking a break from

patching a bicycle tube, Melvin Smylie, 90, talks

about the changes he’s seen along Main Avenue

in the 40-plus years he’s lived there./Photo

by Todd Newcomer. |

Melvin Smylie is not particularly surprised to see me

at his door this Tuesday afternoon, though he’s

never met me before. His light blue eyes, which have seen

nine decades come and go, shine beneath wispy, white brows

that are arched in the question “Can I help you?”

Before I can answer, Mr. Smylie steps outside and gestures

with a slight movement of his head around his front yard,

a repository of bicycles: from road bikes, mountain bikes,

townies with tassels and bells to a whole line of kid’s

bikes propped against each other like falling dominoes.

Melvin Smylie is 90 years old, and this is his life –

rusted bolts, well-oiled chains, resting bike tubes strung

across his yard like laundry in the breeze.

Smylie spends several hours a day, on a good day, taking

apart or putting together bicycles that have been donated

to him. For the past 30 years, people have been bringing

him bicycles and bicycle parts in all states of disrepair,

“saving them a trip to the dump.” Smylie evaluates

the donated bikes, seeing what they need to become roadworthy.

Sometimes all it takes is a semi-new cable, of which he

has hundreds, neatly organized in rusting coffee cans.

Other times, the frame is bent, seat punctured, tires

ripped and the whole thing one big mess – but to

the trained and thoughtful mind, not unsalvageable. In

these cases, Smylie will carefully extract the nuts, bolts,

seat post, chain and anything else that is usable. People

come from all over the Four Corners to buy restored bicycles

and bike parts, though mostly parts, from Melvin Smylie.

|

| A tangle of skewers

and miscellaneous bicycle parts fill a drawer outside

the home of Melvin Smylie./Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

If being 90 and running a business with no advertising,

no employees and no costs other than labor is an anomaly,

then Mr. Smylie’s house fits perfectly into the

story. Melvin lives on 2553 Main Ave., one of the last

of three residences on North Main, sandwiched between

business districts. Smylie and his wife, Willella Maser,

bought the house in 1948 for $7,000 when North Main was

a two-lane dirt road.

“Hell it was dirt road all the way to Denver,”

Smylie muses, with his trademark laugh: head tilted slightly

back, cheeks stretched taut and upper lip barely covering

his top teeth. Melvin Smylie is instantly likable.

When he realizes I’m not here for a bike but an

interview, Smylie invites me inside, and I sit down on

a couch that holds a neat stack of baseball caps and one

bike helmet. His house is exactly as one might expect:

framed black-and-white photos of a beautiful wife (since

deceased), several well-used recliners interspersed with

stunning antiques, a record player/radio tuned to oldies.

Melvin gets comfortable in a recliner, thick tufts of

white hair peeking out from his baseball cap, and starts

telling stories as if this interview business was all

in a day’s work.

“I was born on a homestead in eastern Colorado,”

he says. “You know what a homestead is?” he

asks, narrowing his uncannily blue eyes behind steely

gray frames at this interviewer 60 years his junior. “Government

gave you a piece of land, and if you could improve it

– put up fences, dig some wells and grow a good

crop – why, then in three years it was yours.”

By his early 20s, Melvin had worked the rice fields in

California, broke horses, put up hay and worked the corn

binders in Colorado (“you know what a corn binder

is?” he quizzes). In 1935, at the age of 22, he

went to barber school in Kansas City. It cost him $50

for six months of schooling.

“That was the depression, no one had a car,”

he says. “I bummed rides on the freight train.”

Melvin sent his suitcase ahead of him and joined thousands

of men “riding the rails” on America’s

freight trains. These men climbed down into box cars when

they could, though often their time was spent on top of

the train, exposed to the elements, holding onto the rails

built for the “brakies” to traverse across.

He explains that the government didn’t want a lot

of out of workers congregating in one place for too long,

so this illegal form of travel was rarely discouraged.

“The worst that would happen is you’d get

thrown off and would have to get on another line.”

The freight train stories – lying flat when passing

under a California snow shed, sneaking into freight cars

to search for food, creating friendships and alliances

with the traveling men – tumble from his mouth like

the riders themselves must have, easy and quick, with

no distinct direction.

|

| Mr. Smylie surveys his

stock of bikes and concludes there are just too many

too count./Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

After finishing barber school, riding the rails back

to Colorado’s Front Range and doing a few more stints

on ranches, Smylie saw an ad in a Durango paper seeking

a barber. In style this time, he drove his Model A Roadster

from Denver to Durango. It took two days. Durango was

different then, he tells me. The west side of the 900

block of Main housed the pool halls and beer joints. “The

respectable ladies all walked on the other side of the

street.” He tilts his head for a hearty laugh. “South

of Sixth Street, that was the red light district. You

know about the red light district?”

For 40 years, Melvin Smylie worked as a barber downtown.

“I remember when a haircut cost 25 cents, and a

shave was 15 cents.” He pauses to let that reality

sink in. Smylie remembers shaving the town sheriff: “He

was a beautiful guy to shave. Nice round face, I’d

lather it up and shave him down real easy. No wrinkles.”

Toward the end of his barbering career he bought The Sanitary

Barber Shop, at 937 Main, where Bradley’s Restaurant

stands today. The bike wrenching began when Melvin started

fixing bikes for his grandkids in his free time. Once

he retired, all his time was free and the business simply

evolved.

Melvin takes me outside to tour his motley palace of

bicycles. Nothing is locked up and he admits that “they

steal ’em once in awhile.” He laughs, and

his cheeks stretch across the bone. “Someone steals

a few; someone else brings some in. That’s part

of doing business.” Somehow I doubt these are the

lessons being taught at the Harvard Business School, though

I think Mr. Smylie has cornered the market, not on bike

sales as much as living well.

Lean and fit in Rustler jeans and work boots, Melvin

steps lightly around his property, showing me his storehouse

of parts. Some are in the garage along with his best bikes,

some sit right in the carport where he does his work against

the ceaseless roar of Main Avenue traffic. About the noise

he shrugs and says “I’m used to it.”

He shows me the shelf he built to put his radio on, which

since has been stolen. Running his sinewy hands –

each life line marked indelibly with oil – through

a bucket of water bottles he tells me he got those from

a downtown cycle (pronounced “sick ul”) shop.

There are more parts in his several sheds in the back

yard (roofs held down with wheels and bike frames), buckets

brimming with pedals, seat posts, derailleurs, reflectors,

patch kits, freewheels, cranks, quick-release spokes and

one bag full of bells given to him by a lady from city

hall. He reminds me that mostly he deals in parts, though

just today he sold a bike for $40. “A girl come

in that got her bike stolen and needs transportation to

get to work at Storyville.” The name of the downtown

bar slips off his tongue as if he was a frequent patron,

though most of his socializing takes place at the Senior

Center, a short walk across the street. He has lunch there

every day “with the boys” and is impressed

with the food, especially the salad bar.

“How do you keep track of all these parts?”

I ask.

Melvin looks around, “There’s an order to

it all; it’s a systemized junk shop.”

A few bedraggled stalks of asparagus gone to seed emerge

from the beaten-down grass in his back yard, evidence

of a garden past. Melvin points across the alley toward

West Second. “My daughter used to ride horses up

there, before they had all these trees and buildings.”

His two daughters still live in Durango and come by on

a daily basis.

“These three bikes just come in.” He gestures

to a tangle of mountain bikes leaning up against the mammoth

blue spruce that he planted in 1950.

“Are they any good?”

“They will be after I fix ’em up.”

|

| Melvin Smylie works

to locate a leak in a bicycle tube and apply a patch./Photo

by Todd Newcomer. |

Mr. Smylie has people knocking on his door all hours

of the day, looking to get or get rid of something. “Yesterday

a fella from Aztec come up to get a Shimano piece for

his coaster breaks. I had the very part he was looking

for, right serial number and everything,” he beams.

Melvin has fixed lawnmowers and horse halters. He’s

sold bikes to Europeans who wanted a way to travel within

the West’s National Park system.

“It’s kinda fun,” he says “all

the different people you meet.”

He has a great rapport with the downtown cycle shops,

they send people his way, and if he needs a special wrench

he can go down and use theirs for free.

Smylie quit riding bikes last year when he turned 90,

though he takes a daily walk and does push-ups and sit-ups

every night. His mind is well oiled and spins with a rhythmic

balance of work and play.

“What do you do in the wintertime?” I ask.

“Watch football and read Westerns,” he says.

“And sell parts.” His lips spread in a smile.

Mr. Melvin Smylie has seen a different world bloom as

an old way of life has gone dormant. He knew Durango when

a barber could afford to buy a home in town for his family.

He remembers when his neighborhood was a peaceful, residential

zone. But he’s not bitter. He thinks the Rec Center

is a beautiful building.

Looking back at it all, he says “I’ve seen

a lot in my lifetime and had a pretty good time. If the

Lord wants me tomorrow, I’m ahead of the game.”

As I ride away on my bike, full of gratitude for the

stories I’ve heard, Melvin calls after me “keep

riding your bike, it’s good for you.”

|