A little

tree trimming

"And this is a salt cedar," she

crooned proudly as we approached the fully grown tree. Her fingers

moving tenderly through its needles, she described the lovely

purple bloom it displayed in spring. She also remarked on how well

it had become a part of the garden, filling up that corner nicely

and complementing the columbine and lupine just perfectly. I

resisted the urge to reply, bit my lip and patiently hung on

through the rest of the real estate tour. Eventually, we put the

house under contract and patiently waited the 30 days prior to

closing.

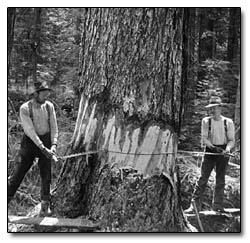

One of the first things

I did after moving in was mix up some two-stroke oil and gas, fire

up the chainsaw and rip into the salt cedar's trunk. The whirring

blade bit into the same branches that had been caressed a month

prior. I took the tree down in three separate pieces, delighting in

the cuts, and on my final pass, I shaved the stump close to the

ground trying to erase any mark of the tree's existence. Then I

bucked the beauty up and put it on the top of the burn

pile.

Purple blooms and

complementary colors aside, that salt cedar is known by another

name outside the realm of the nursery. And I had no plans on having

a tamarisk, the scourge of the West, growing happily in my front

yard.

Cutting down a tree is

serious business in this day of hungry paper mills and salvage

logging. It's particularly difficult to drop a tree that was

deliberately planted, cared for and nursed into adolescence.

However, having a tamarisk in the front yard would be akin to

keeping a hyena as a pet. The tree is completely alien to the west

and America, having been deliberately introduced as a landscape

ornamental. It also has no natural predators and has spread

unchecked for the last 50 years, squeezing out natives, sucking

rivers dry and destroying habitat. It is little more than a giant

weed and is sadly not even the most significant threat to the

natural landscape of La Plata County.

In an earlier Durango

house, I fell in love with the seemingly mature trees in the back

yard. The following spring, the trees were the first to leaf out

and then by surprise, they starting dropping thousands of seed pods

in the yard. The little medallions formed windrows in our flower

beds and even got into trays of vegetable starts. Weeks later,

hundreds of shoots started poking their heads up everywhere. Our

old-timer neighbor passed by one day and chuckled as he saw us

weeding beneath the 80-foot-tall trees. "I see you've met your

Siberian elms," he said. "Man, those things are a pain in the ass.

And you know what? I bet those trees have only been there for 15

years." I found myself mixing oil and gas.

Last weekend, as we

floated into the relatively pristine, wilderness stretch of the

Lower San Juan River in Southeast Utah, there were no Siberian

elms. However, tamarisk was everywhere. It blotted out river banks,

covered one-time beaches and draped over the river, threatening to

close narrow stretches altogether. A vast number of Russian olives,

another ornamental tree gone bad, intermingled with the

tamarisk.

I was surprised when a

member of our party and a Durango resident said, "Boy it's nice to

see all these olives against the red rock. It really reminds me of

my upbringing."

Another chimed in,

saying, "It's just a shame we weren't here a little earlier for the

bloom. The smell is just intoxicating."

Once again, where my

eyes saw blight, others were overwhelmed by beauty. But the canyon

told its own tale. These thorny ornamentals hindered progress on

side hikes. They surrounded stands of ancient, gnarled cottonwoods

and were choking them out. Hundreds of miles from the nearest

landscaping, Russian olives were growing everywhere, flourishing in

sand and cracks in the rock.

Knowing that the tree

was beginning to get a foothold on the banks of the Animas River,

the view was an especially upsetting one. My thoughts turned to a

federal push to eradicate tamarisk and efforts in Durango to get a

handle on Russian olive.

But then someone

commented, "It seems like the kind of tree you could enjoy in your

yard as long as you kept an eye on it." The comment neglected the

real reason the trees were spreading in Durango, in Farmington and

Cortez, in the canyons of the Lower San Juan and throughout the

Colorado River Basin someone bought a tamarisk, a Siberian elm or a

Russian olive at a nursery, planted and tried to keep an eye on

it.

The spread of these new

neighbors began in private yards. Maybe we should start getting a

handle on them there as well. Once you know what you're dealing

with, mixing up a little gas and firing up the chainsaw can be a

pretty gratifying experience.

-Will Sands

|