|

A bulldozer of the C&J

Gravel Co. sits idle Monday afternoon on Ewing Mesa. The

gravel company, which operated on BLM land, has a permit

to mine 30 acres. Recent plans to expand the pit have forced

the rerouting of parts of the Sale Barn

and Cowboy trails, which were in the permit area./Photo

by Todd Newcomer. |

Bikers and hikers who have finally mastered

the newest additions to the Horse Gulch Trail System on Ewing

Mesa may notice a few new twists and turns in their favorite

trails. And chances are, detours and disturbances may become

a recurring theme in the future.

The largely undeveloped mesa, a patchwork of private and public

holdings, including 1,600 acres of Bureau of Land Management

Land, has long been home to area wildlife and – more recently

– a network of trails. However, the mesa also sits on

top of millions of tons of unmined gravel. While gravel mining

on the mesa is nothing new, it is expected to increase as the

need for raw material escalates with Mercy Medical Center breaking

ground soon and a slew of smaller developments waiting in the

wings.

And although the trails, which are deeded to La Plata County

and maintained by Trails 2000, are not in jeopardy per se, reconciling

the multiple uses on the mesa has become increasingly tricky

to negotiate.

“All the parties are coming together and trying to come

up with the right plan,” said Bill Manning, director of

Trails 2000. The volunteer-based organization recently rerouted

the south end of the Cowboy Trail and the east end of the Sale

Barn Trail to accommodate an expansion of the C&J Gravel

pit. “We did it in four evening work efforts. Fortunately,

we had a lot of energetic volunteers,” Manning said.

Still in the works is a reroute of the lower half of the Carbon

Junction Trail, which crosses land that will be mined by Four

Corners Materials, the other gravel operation on the mesa. While

the C&J pit, on the east side of the mesa, is on BLM land,

the Four Corners Materials pit, on the west side, is on private

land. It is leased from Oak Ridge Energy, which is owned by

the Pautsky family, who wants to some day develop the land.

Plans call for 1,725 new homes, a golf course and commercial

buildings on about 1,000 acres. However, the original owner

of the land, Noel Pautsky, also left provisions in his will

for a 10-foot easement for the trails across the parcel.

Manning said the reroute of Carbon Junction is expected to

take some time because of the numerous entities involved.

“It’s more complicated because of the patchwork

of different ownership,” he said. “The trail is

partially on private land, partially on public land, and the

trail’s owned by the county.”

Richard Speegle, recreation project leader for the San Juan

Public Lands Center, said he was not sure when the Carbon Junction

reroute would be completed, but that it is in the works.

“We needed to do an environmental analysis, and we’re

in the process of doing that now,” he said. “Then

we need to flag the new route.”

|

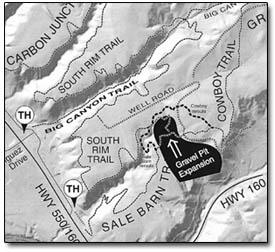

The south end of the Cowboy

Trail and the east part of the Sale Barn Trail were recently

rerouted around the planned expansion of the C&J Gravel

pit. Future

plans call for rerouting the bottom portion of the Carbon

Junction Trail (top left) around the gravel operations of

Four Corners Materials./Map courtesy Trails 2000. |

Changing demands

Speegle said accounting for recreational uses on the mesa is

a relatively recent development in managing the area.

“In the original 1986 management plan, nobody acknowledged

recreational use up there,” he said. “It was looked

at for its wildlife emphasis and its mineral emphasis.”

However, as the area became increasingly popular with bikers,

hikers and horseback riders, the BLM amended the plan to account

for the changed usage.

“When we saw how much demand there was from Horse Gulch,

we did an environmental assessment and changed the emphasis

to include recreation,” he said. This resulted in the

developed trailheads, signage and maps that have sprung up along

the trails in recent years, he said.

Speegle said that although there are three areas – wildlife,

mining and recreation – that now must be considered when

managing the parcel, all are weighed equally.

“There is no one that is favored over another,”

he said.

Nevertheless, he said the BLM has no say over the development

pressures that seem to be driving the future face of the mesa.

“Basically, they are munching on it from both sides,”

he said of the gravel mining.

Speegle said that a recent geological study concluded there

were 160 acres of gravel on the mesa, a veritable mother lode.

“Really, that gravel is a gold mine, ” he said,

adding that it also is close to the surface, making it even

more valuable for its ease of extraction.

Manning pointed out that, while mining may not be popular in

the public’s eye, it provides a crucial source of cheap,

plentiful material – essential fuel for the county’s

rapid growth.

“Our community has a high demand for gravel,” he

said. “Every time we drive on a road there is gravel underneath

it. We’re all using it.”

And, he notes, the appetite is only going to get bigger.

“I fear the demand for gravel will go sky high with Grandview,

the hospital, River Trails Ranch, Ewing Mesa – if it all

goes in.”

Appetite for gravel

John Gilleland, Vice President of C&J Gravel, a family-owned

business that has been operating for 26 years, said his business

already is gearing up in anticipation of the growth.

“The hospital project will include a lot of material,

and our production will increase,” he said. He said C&J

wanted to be prepared when that time came, which meant working

with Trails 2000 to reroute the Sale Barn and Cowboy trails.

“We wanted to make sure the trails were rerouted before

we got into that area,” he said. “We like to work

ahead of ourselves.”

He said C&J, which holds a permit for 30 acres or 1.2 million

tons of gravel over 10 years, whichever comes first, extracts

about 220,000 tons of material a year from the Ewing pit. The

company is expected to hit its tonnage quota before mining the

entire 30-acre permit area, he said.

Nevertheless, he admitted it is possible that the rerouted

Cowboy and Sale Barn trails may need to be moved again in the

event of a future expansion.

“The rerouted trails are still in the permit area,”

he said. “It’s possible they will need to reroute

the reroute.”

According to Speegle, it is hard for gravel miners to gauge

just how much material there will be in a particular location

until they break ground.

“Gravel mining is a little bit of a moving target,”

he said. “They don’t know where the best seams are

until they dig it up.”

However, Gilleland said he expects only about half of the permit

area will be mined.

“Of that 30 acres, we’ll end up using 15 to 20

acres, and we’ll hit our quantity,” he said. Furthermore,

the company only clears land it intends to mine.

“It wouldn’t make sense to clear all 30 acres,”

he said. “We try to have the least impact. We go in and

clear just ahead of our operations.”

And while Gilleland admits his operation has the largest physical

impact on the mesa, he said steps are taken to mitigate the

damage and help return the land to a usable state. For starters,

for every ton of gravel extracted, C&J pays 10 cents into

a federal fund that documents and excavates cultural sites.

Additionally, the company pays $300,000 a year to the BLM in

royalties, about $30,000 of which goes toward site mitigation.

One machine that is used to sculpt reclaimed slopes costs him

$500 a day in gas, and once the drought lets up, grass will

be planted in the reclaimed areas, he said.

“It costs us a lot of money to mitigate this land,”

he said.

Furthermore, he said C&J tries to help out with trail projects

any way it can.

“We donate equipment and material for trailheads, parking

lots, etc.,” he said, adding that he helped get the Durango

BMX track up and running. He said it also is his hope to improve

access to the mesa as well as parking.

“I have been proposing more public access to the mesa,”

he said, “parking, possibly a BMX track. There’s

a lot of dirt up there.”

Although it is impossible to return the land to its premining

state, Gilleland said the area may end up being more functional

from a recreational standpoint after reclamation.

“Basically, what’s going to happen is, this land

– which was a rocky mesa – should have a very significant

potential for public recreation,” he said.

All trails lead to one

Speegle, of the BLM, also speculated that, if Grandview, with

its proposed 2,500 residences, and Oak Ridge, with 1,700 residences,

go through, the BLM parcel may very well be the only open space

left on the mesa. And although the BLM is not allowed to trade

the 1,600-acre parcel with a private entity, it could make a

swap with a public one – namely the city of Durango.

“It would be my guess that it would become city property,

and the idea would be to keep it open space,” he said,

adding that the possible addition of thousands of more people

is a sobering one. “If you think long term, that’ll

be like the Mountain Park with the city on both sides.”

In the meantime, Speegle said it’s his job to make sure

the land is being managed in the best interest of its stakeholders.

“It’s truly a multiple use area,” he said.

“All the parties are working closely together to make

sure those trails are running and to not damage wildlife habitat.”

Manning said so far he is pleased with the cooperative effort.

“We’re excited we’re able to protect the

continuity of the trail system by putting in reroutes,”

he said.

And when all is said and done, Gilleland said he believes such

cooperation will create a mutually agreeable situation for all.

“In the end, the land will be usable, and we will have

extracted a valuable resource,” he said. “Houses

need to be built; roads need to be built. Everybody needs a

rock sometime.”