|

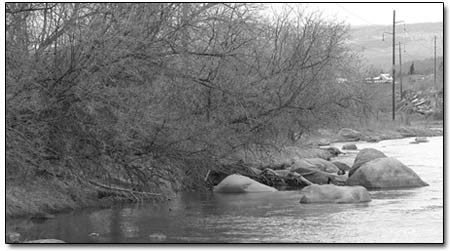

| A stand of Russian Olives

crowds the banks of the Animas River below Santa Rita Park.

/Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

Despite recent discussion of

beetles, fires and drought, several species of local trees are

not merely surviving, they are flourishing. In fact, Russian

Olive in particular is doing so well, it is taking over the

Animas River valley and squeezing out native plants and trees.

However, several local groups and one man in particular are

intervening on the local environment’s behalf and grappling

with what amounts to a large scale infestation of weeds.

Barry Rhea of Rhea Environmental Consulting first dealt with

the ugly side of Russian Olive over four years ago in Northern

New Mexico. “I was doing bird surveys along the San Juan

River in New Mexico and was getting the shirt ripped off my

back trying to get into those areas,” he said. “I

was amazed how Russian Olive and to a lesser degree Tamarisk

had taken over that river corridor.”

Rhea’s eyes were opened even wider when he came home

to Durango and realized that Russian Olive had made an entrance

into the Animas River valley and was beginning to spread. “I

realized that we were in an early stage of what the Farmington

area was in 30 years ago,” he said.

Rhea explained that problems associated with Russian Olives,

and also Siberian Elm and Tamarisk begin in urban areas. The

non-native trees are actually Eurasian in origin and have been

sold by nurseries as hardy, attractive and quick growers. However,

a lack of natural predators make the trees a threat to everything

around them, and unchecked, they spread rampantly from front

yards into river corridors and beyond. In response to this spread,

the State of Colorado declared Russian Olive a noxious weed

two years ago, and last December made it illegal for nurseries

to sell the tree.

“Bird species eat fruit on ornamental trees and then

fly down to the river, roost in the cottonwoods and pass the

seed,” Rhea said. “One mature Russian Olive produces

thousands of seeds. Once Russian Olive gets established in the

river corridor, the invasion takes off.”

Contrary to widespread belief that Russian Olive is a harmless

tree and any tree is a good one, the impacts of the invasion

can be severe, Rhea added. “It basically overtakes the

native vegetation, like willows, hawthorn and alder, and it

keeps cottonwoods from regenerating under the mature trees,”

he said. “Eventually, it begins to compete for moisture

and nutrients with the mature cottonwoods and they being to

decline. Once, it takes over the river corridor, it starts moving

out into farmland and pasture like you can see down in Aztec.”

Rhea noted that in many areas of northern New Mexico the damage

has been total and irreversible, saying, “Basically Farmington

and Aztec have lost their river valleys. With the current technology,

there’s no way to deal with what’s down there either

from an ecological or economic standpoint.”

However, the Animas River Valley from Hermosa to the Colorado-New

Mexico border still has a fighting chance as long as the local

community moves quickly, according to Rhea.

|

| Barry Rhea gets into the thick of things

and treats several Russian Olives, trees that are crowding

out the banks of the Animas. “It’s a painful,

bloody process,” says Rhea. /Courtesy photo |

“On the Animas now, the native vegetation is still intact,”

he said. “The question becomes, how do we protect it.

We have an opportunity now to stem the tide, but that window

of opportunity is closing fast.”

During the last four years, Rhea has developed a means of snuffing

the Russian Olive, a tree which resists even the chainsaw. Working

on stands on Sugnet Ranch immediately north of Durango and the

Wiley family’s property immediately south of Santa Rita

Park, he developed this technique. In each location, he has

downed small trees and treated the stump with herbicide or drilled

holes around the bases of larger trees and filled them with

herbicide. “If you just cut the tree down they sprout

back,” Rhea said. “It requires the use of an herbicide.”

Rhea added that most Russian Olives are a thorny tangle and

the work is anything but glorious. “It’s a painful,

bloody process, and it’s one tree at a time,” he

said. “Believe me it’s not what I want to do with

the rest of my life.”

To date, Rhea has treated approximately 1,000 trees in and

around Durango but has only scratched the surface. However,

momentum has been building in the community and awareness has

been spreading. Ron Stoner, the City of Durango’s Arborist,

has begun working with Rhea to help solve the problem. Stoner

said that the city is taking a very aggressive stance against

Russian Olive and other invasive trees.

“The city’s perspective and general direction is

that we’re going to have a plan of systematic eradication

within city limits,” he said. “We’re going

to slowly work through our park system and city lands adjacent

to the river, and we’re going to try to remove all of

the Russian Olive that’s been planted around city buildings.”

Recently, 15 mature Russian Olives were removed at the city’s

service center in Bodo Park and Stoner said that the city is

digging in for the long haul. “We’re going to keep

it ongoing as long as it takes,” he said. “I don’t

think it will ever end but we are in motion.”

In addition to Russian Olive, the city will be grappling with

the spread of Siberian Elm and Tamarisk. “Tamarisk of

course is considered a top priority and we will also target

Siberian Elm,” Stoner said.

Local efforts are also on the verge of getting a boost from

some much needed funding. The Friends of the Animas River are

close to receiving $7,000 in grant funding to help control Russian

Olive, a tree Executive Director Anders Beck calls “the

scourge of the Animas.”

Beck is hoping that grant funding will be a start for long-term

chain of funding for what will have to be a long-term project.

“It’s such a large scale project that it’s

been hard to get off the ground,” he said. “But

from here, hopefully we can start building a track record.”

Rhea added, “It isn’t a lot of money compared to

the problem, but it’s a start. What we hope to do with

this seed money is some control along the river and also do

a survey from Hermosa to the Colorado-New Mexico border to define

the extent of the problem.”

Rhea and Beck are also hoping to invest energy into education.

Along with Stoner, they all agreed that the largest burden rests

on private property owners, many of whom planted the trees in

the first place.

“You can do all the eradication you want along the banks

of the river and then a Russian Olive on private property can

reseed the riverbank,” Beck said. “This begins with

individuals and we really believe people who live in proximity

to the river want to be good stewards of the land.”

Rhea added, “A huge piece of this whole thing is education

and letting people know that the beautiful tree growing on their

property is a threat to the Animas and its habitat.”

Last summer, a FOAR intern compiled a list of affected property

owners and contacts will be made.

“Most of the progress has occurred on public or quasi-public

lands and most of the problem is occurring on private land,”

Rhea said. “We’re not trying to point our finger

at anyone. It’s just that most people don’t know.

Russian Olive can be a really beautiful tree and it’s

hard for people to cut them down.”

Leaving the trees intact will result in only one other option,

according Rhea. “What is now a riparian corridor dominated

by native trees and shrubs will become a river corridor dominated

by Russian Olive, Siberian Elm and Tamarisk,” he said.

“The impacts to wildlife and particularly migratory birds

could be huge.”

For more information, call 247-2388 or 375-2696 or check out

the Friends of the Animas River website at www.foar.org.