|

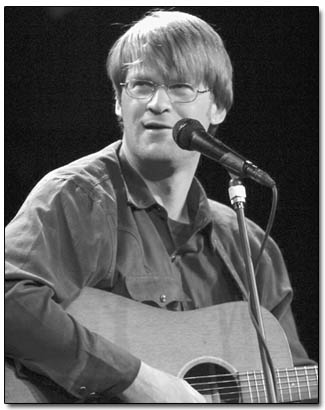

Singer-songwriter

serves up country music with alternative flavor written by Missy Votel

Take

one part Tabasco, throw in a heaping helping of prickly

pear, add a dash of patchouli oil, mix well in a margarita

shaker, grill over an open fire under the stars, serve

up with a Southern drawl, and you’ve got local singer/songwriter

Sand Sheff. Take

one part Tabasco, throw in a heaping helping of prickly

pear, add a dash of patchouli oil, mix well in a margarita

shaker, grill over an open fire under the stars, serve

up with a Southern drawl, and you’ve got local singer/songwriter

Sand Sheff.

With a voice reminiscent of Jimmy Buffett’s that

has invited comparisons to a young John Prine, and lyrics

that run the gamut from truck drivin’ and cow wranglin’

to hard lovin’ and moon shinin’, Sheff offers

up a unique take on traditional country and western.

In its simplest classification, Sheff said his sound

fits into the alt country genre, an ambiguous term for

countrified artists who don’t quite fit the mainstream

mold.

“I’d call it Okie, jamalicious grass funk

if I could say it with a straight face,” he said

when pressed to define his sound.

The 35-year-old singer, who calls Durango home, attributes

his unique sound, at least in part, to his diverse past.

Over the years, Sheff has been a short-order cook, cowboy,

recording artist, bus washer, firefighter, minister and

author, in no particular order. He has lived across the

United States, from the most remote reaches of the Utah

desert to the bustling streets of Nashville.

“I

have lived around cowboys, and I have lived around hippies,”

he said. “And we all have a lot in common, whether

we know it or not.” “I

have lived around cowboys, and I have lived around hippies,”

he said. “And we all have a lot in common, whether

we know it or not.”

Born in Flagstaff, Ariz., Sheff soon moved to Tahlequah,

Okla., a small town at the foot of the Ozark Mountains.

Situated squarely at a crossroads between the South and

West, Sheff said the region provided him a unique perspective

on traditional American music and culture.

“It was almost in the West; almost in the South,”

he said. “Life was a lot slower there. People would

sit around on the porch just like their granddad did;

they were deeply rooted.”

And while Sheff said bluegrass was the music de rigueur

for those parts, the twang of the banjo was not what drew

him into the musical realm.

“I heard the Beatles, and all of a sudden I was

so possessed, it changed everything in me,” he said.

Inspired, an 11-year-old Sheff bought his first guitar

for $40 and coaxed three friends into doing likewise.

“After three months, I was the only one still playing,”

he said. “And it’s been my best friend ever

since.”

At the age of 18, Sheff headed west to Colorado Springs,

where he went to Colorado College on an English scholarship.

Upon graduating, he was so smitten by the Western landscape

that he decided to make it his new home. With guitar in

tow, he began bumming around the wide-open spaces of the

Four Corners, which included stints baking at Carvers

in Durango and wrangling horses near Moab. He finally

settled in a tiny outpost in south-central Utah: Fry Canyon,

population 6.

“I had gone as far away as I thought I could from

civilization,” he said. “There’s more

Anasazi spirits there than people.”

During his time in the Four Corners, Sheff played gigs

at venues ranging from the old Farquahrt’s stage

to rustic campfires. He also landed his first recording

gig, which resulted in his first two albums, “Quicksand

Soup” and “Highway 666.”

However, the wanderlust that brought Sheff to the West

soon resurfaced. At the age of 27, he packed his bags

for Nashville.

“I knew I was running into a dead end, and I knew

I had to leave,” he said.

The young singer sold his house, loaded up his truck

and, with burning clutch, drove to Nashville. “I

just threw myself out there at the mercy of the universe,”

he said.

The cosmos must have been smiling, because just as the

clutch heaved its last breath, Sheff pulled up to a friend’s

house in Nashville. It was there that he coincidentally

met a mutual friend who would go on to become a member

in his new band, Buck 50.

“We both ended up at a friend’s house on

the same day,” he said.

Sheff’s luck was about to get better. At Buck 50’s

first gig, there was a record producer in the audience

who goaded them into the studio. “He said, ‘I

want to get you in before you practice too much,’”

Sheff recalled.

Within weeks the band had cut its first CD, “Red

Dirt Road” and was on its way to establishing itself

as one of the premiere acts in Nashville.

“We sold some records; we thought we were going

to hit the big time,” Sheff said.

However, for whatever reason, Buck 50 never quite made

the crossover from alternative shores to the mainstream.

“What we did was so raw,” he said. “We

would go from psychedelic to getting completely bizarre.

I think the Nashville gatekeepers thought it was a little

raw.”

Within two years, Buck 50 was history, and Sheff was

striking out solo. However, after three more years and

what would turn out to be his biggest production yet,

“Turn Me Around,” Sheff once again received

the calling to move.

“I woke up one morning and left Nashville,”

he said.

And while he admits Nashville is not necessarily conducive

to fostering independent artists who challenge tradition

such as himself, he said he has no regrets.

“Nodoby makes it in Nashville; Nashville chooses

who makes it,” he said. “Nevertheless, people

were really good to me. I had three records that were

paid for by other people, produced by other people.”

Once again with fate as his guide, Sheff headed west

in 2000. Taking a hiatus from his music, he fought fires

in Montana and Oregon and eventually ended up back in

the desert, this time Bluff, Utah. Here he met his future

wife, Alisa. Two months later, the two were married and

settled in Durango, where Alisa lived. Once back in Durango,

Sheff said he was motivated to resume his music career.

“I was lying low, finishing this book I was writing,

and all of a sudden, the music started flowing,”

he said. With his spirit renewed, Sheff organized the

first ever “Survival Revival” in the spring

of 2002, something he defines as part minstrel show, part

theatrical production and part musical performance, all

with the underlying theme of “keeping it real.”

The show was Sheff’s first live gig since leaving

Nashville two years earlier and served as the catalyst

for regular gigs around town. Sheff said his return to

the spotlight has been good thus far, and he has enjoyed

the interaction with the public.

“I call myself the human jukebox,” he said.

“People try to stump me. Someone the other night

hollered out Meatloaf, but I got it.”

And while Sheff is still happy to play covers, he has

formed a band made up of local musicians Jimmy Craighead,

Pat Dressen, Glen Keefe and Bob Wennerson, which performs

originals. He also is holding his second annual Survival

Revival this Saturday and plans to hit the studio this

spring to cut a new record, which should be out by this

summer.

“It’s going to be my best record ever,”

he said. “I’ve got five years’ worth

of material built up.”

Of course, in keeping with the ever-morphing Sheff style,

he promises it will be unlike anything he has done to

date. Beyond that, he said he’s open to just about

anything fate throws at him.

“It’s a funny life,” he said. “If

you jump right out there, all this weird stuff happens.”

|