|

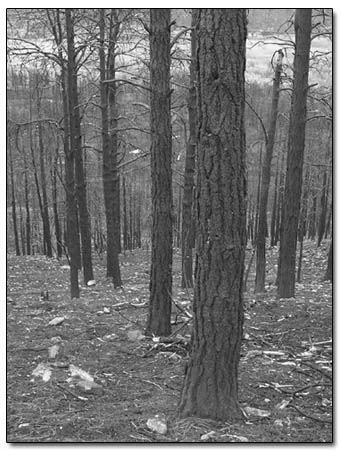

Burned ponderosa pines, like

these overlooking the Animas Valley, would be logged under

a salvage logging plan being proposed by the Forest Service.

However, the plan is being criticized by local enivironmental

groups Colorado Wild and the San Juan Citizens’ Alliance

for being a thinly veiled effort by the

Bush administration to cater to the timber industry.//Photo

by Todd Newcomer. |

As Jeff Berman, Colorado Wild’s executive

director, flips through the phone book-sized document, his comments

are anything but positive.

“There are dozens of typos,” he said pointing to

a table.

A handful of pages later, he commented, “There are whole

sections of text that should be elsewhere.”

Looking at another table, Berman said, “Either their

math is wrong or they’re leaving things out.”

In general, Berman has a blunt opinion of the recently released

environmental impact statement on salvage logging in the Missionary

Ridge burn area.

“They should take this back,” he said. “This

is one of the sloppiest environmental impact statements I’ve

ever seen. There are whole issues missing. There are a bunch

of scientific issues that are not even addressed.”

The San Juan National Forest released the EIS last week as

a precursor to harvesting a large number of trees burned in

last summer’s Miss-ionary Ridge fire. The document is

available for public review, and based on that review, the Forest

Service will determine how to proceed with the proposed timber

sale.

Dave Dallison, timber program leader for the San Juan National

Forest, said that the Forest Service’s preferred alternative

would entail logging on roughly 4,200 acres of the approximately

70,000 acres burned in the giant wildfire. The harvest would

be accomplished by standard ground-based logging, cable logging

and helicopter logging.

“The primary purpose of the program is to salvage dead

and dying timber that would otherwise be lost,” Dallison

said. “We’d like to do that without causing significant

resource damage. Two of the side benefits would be fuels reduction

for future wildfire situations and the destruction of some beetle

populations.”

In the fast lane

Dallison agreed with Berman that the review of the sale is

rushed. However, he remarked that speed is a necessity.

“It’s on an extremely fast track, probably half

the time it normally takes,” Dallison said. “This

is the time frame because of the deterioration of the timber.”

Dallison notes that as soon as trees die, they begin rotting.

Consequently, marketable lumber, particularly ponderosa pine,

must be harvested as soon as possible. “The first to go

is the ponderosa pine,” Dallison said. “We only

have 18 months to salvage those trees.”

Aspen, Douglas fir and Englemann spruce have slightly more

forgiving time frames, according to Dallison, but they still

lose their value after a couple years.

However, Colorado Wild is not buying Dallison’s argument,

and the conservation organization views the timber sale as too

massive, rushed, reckless and potentially damaging to the environmental

and social fabric of La Plata County. While the logging has

been proposed as a clean-up and use of already dead trees, Berman

said that operation would amount to a total clear-cut and would

be on a scale never witnessed in this part of the state.

|

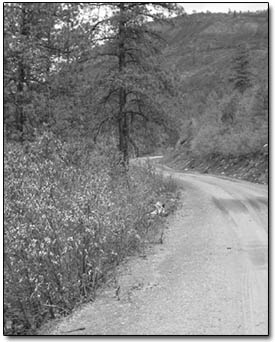

| Missionary Ridge Road, seen here, could

become the site of increased truck traffic this summer if

a plan to harvest burned timber in the Missionary Ridge

area gains approval. According to Jeff Berman, of Colorado

Wild, the harvest could mean up to 4,000 trucks on local

roads./Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

“They’re proposing to harvest 20 million board

feet of lumber,” Berman said. “That’s about

4,000 logging trucks’ worth. If you had a green timber

sale this size, it would be accomplished over three to 10 years.

They want to do this over three to six months.”

Feeding the industry

Dallison noted that in spite of the project’s size, the

demand for the trees exists, and the timber industry has expressed

interest. “Before we embarked on this, we talked with

industry extensively, and the sense was that they were very

interested,” he said. “It just depends on what’s

going on with the market at the time. It has been up, but I

just heard today that housing starts are down.”

Berman countered that regardless of the timber industry’s

interest, capacity would be an altogether different issue. Lumber

mills in Mancos, Montrose and Espanola, N.M., have apparently

expressed interest in processing the load and adding shifts

to do so.

However, Berman raised the question of what happens to the

workers when the sale is over. “They either increase the

amount of timber coming off our public lands or they lay off

all those people,” he said. “The Forest Service

will either be encouraging levels of industry they can’t

sustain, or they’ll be creating a boom-bust cycle.”

Berman said that in his mind, the big push for this operation

is coming not from the Forest Service but higher up the chain

of command. He said that the Missionary Ridge salvage operation

and five others proposed for the state are the result of President

George Bush’s Healthy Forests Initiative and amount to

timber grabs in the name of fire suppression.

“This is driven at the whim of the timber industry and

at the behest of the Bush administration,” Berman said.

The cost to community

While the industry has expressed interest in the sale, Berman

stressed that Durango should be aware of the direct impacts.

“Can this community afford another destroyed or even

harmed tourist season?” he asked. “There’s

going to be heavy logging truck traffic around Bayfield High

School when school’s letting out. I’m not going

to even consider riding my bike on East Animas Road during this.

They’re also going to have to close whole areas of forest

to do this. That’s going to hurt out tourism and more

businesses are going to be stretched to the limit.”

Berman went on to name a laundry list of impacts on the area’s

natural environment, including total clear-cuts, erosion and

weed proliferation, among other issues. Citing the 1995 Beschta

study, Berman said that salvage logging actually does not enhance

fire suppression, and burned areas are extremely vulnerable

to impacts. According to the study, salvage logging actually

creates a warmer, drier microclimate that increases fire danger.

The study also found that logging damages soils through increased

erosion and compaction.

“An area that’s been burned is much more sensitive

to impacts,” Berman said.

Road to nowhere?

One of the chief impacts of the harvest would be related to

roads. Berman noted that while the EIS said that very few roads

would be built, it does name 90 miles of “roads”

that will have to be improved or reconstructed. He added that

the EIS does not map or describe where these roads are.

“Most of this project is going to be ground-based logging,”

Berman said. “They’re proposing to use what they

call existing roads, but the road analysis is not available.

There’s no opportunity for anyone to go see what the condition

of these roads are, or if they’re even roads or trails

or double-tracks.”

Because of the sum of potential impacts, Berman said his group

will strongly oppose the proposed salvage operation. “There

may be a few areas that they could go up there and log,”

he said. “But they’re not acknowledging the scientific

research, and theydoing nothing to assess the impacts.”

Another group likely to challenge the EIS is the San Juan Citizens’

Alliance. Mark Pearson, executive director, said that his group

has yet to pick apart the document but already has issues.

“I think we’ll have some of the same concerns as

Colorado Wild,” Pearson said.

Offhand, he listed logging on steep slopes, helicopter logging

within roadless areas and road reconstruction as potential problems.

“There’s an awful lot of miles of roads to be reconstructed

up there,” he said. “Ninety miles is a great deal

of new permanent road.”

From consensus to discord

Like Berman, Pearson referenced the Beschta study. In particular,

he noted that San Juan Citizens’ Alliance had presented

the study’s findings to the San Juan National Forest during

the creation of the EIS. He said he was disappointed to see

no mention of it in the EIS.

“It looks like they totally blew us off and didn’t

even mention it,” Pearson said. “That’s disconcerting,

considering it was compiled by 20 Forest Service scientists.”

On a broader level, Berman said the EIS is disconcerting as

it represents a break in the long history of consensus building

by the San Juan National Forest. Given good past relations with

the public agency, he said he is surprised by this shift.

“They are turning that on its head with this,”

he concluded. “I’m actually surprised. I thought

they would be a little more fair.”