|

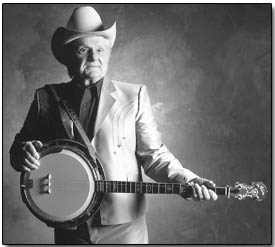

A converation with Ralph Stanley

written by Missy Votel

When

it comes to staying power, Ralph Stanley knows a thing

or two. Not only does he deliver a haunting, trembling

tenor that stays with a listener long after a song’s

ending, but he’s done so for more than half a century. When

it comes to staying power, Ralph Stanley knows a thing

or two. Not only does he deliver a haunting, trembling

tenor that stays with a listener long after a song’s

ending, but he’s done so for more than half a century.

Stanley’s resume at 76 reads every bit the living

legend he is with three Grammys, a Library of Congress

award and numerous International Bluegrass Awards. He

credits his longevity to his down-home values.

“I took pretty good care of myself; I lived a clean

life,” he said Tuesday from his home in Coeburn

County, Virginia. “I guess the Lord has blessed

me.”

And with a two-year-old granddaughter climbing on his

knee, one gets the feeling Stanley is every bit the genuine

article he says he is.

“I

think the reason I’ve lasted so long is because

I’m making the same old-time sound that I started

with,” he said. “I believe in sticking with

what you start with. I do it like I feel it, and I think

that’s the reason I’ve stayed around so long.” “I

think the reason I’ve lasted so long is because

I’m making the same old-time sound that I started

with,” he said. “I believe in sticking with

what you start with. I do it like I feel it, and I think

that’s the reason I’ve stayed around so long.”

Indeed, even the name of Stanley’s band, the Clinch

Mountain Boys – named for the Clinch Mountains of

Virginia where he was born in 1927 – has remained

steadfast over the years. It was here that Stanley first

picked up a banjo, learning his famous “clawhammer”

style from his mother. By 1946, Stanley and his older

brother Carter were playing regular radio gigs under the

Stanley Brothers moniker. A year later, the two made their

first recording, paving their way toward becoming renowned

purveyors of bluegrass, a sound pioneered by their contemporary

Bill Monroe. And although to this day Stanley’s

music is still classified under the bluegrass genre, he

contends it may not be the best description of the rustic

Stanley sound.

“Sometimes I don’t call mine bluegrass,”

he said. “It’s more old time, more in the

mountains. Mine is a bit older.”

And although the years between 1949 and 1952 are considered

by many to be the Stanley Brothers’ heyday, it wasn’t

until recently that Stanley struck gold – or more

precisely, platinum – with his music. In 2001 the

soundtrack from “O Brother Where Art Thou,”

which features Stanley’s a capella version of his

classic “O Death,” the Stanley Brothers’

“Angel Band,” as well as Stanley’s “Man

of Constant Sorrows” covered by Union Station, broke

the 5-million mark.

“‘O Brother’ got me a lot of new listeners,

new fans I never would have had,” he said. “I’ve

got a third more fans now than before.”

Stanley, who has been on his own since the death of his

brother in 1966, also has gained the admiration of many

peers. Over the years, he has collaborated with artists

ranging from Bob Dylan and BR-549 to Iris DeMent and Lucinda

Williams. His band has been the springboard for many a

young bluegrass superstar, including Ricky Skaggs and

the late Keith Whitley. Likewise, the music of the Stanley

Brothers has been revived by younger artists from Emmylou

Harris and Gillian Welch to Dan Fogelberg and Dwight Yoakum.

Perhaps the most notable development of the bluegrass

sound pioneered by the Stanley Brothers, Monroe and Earl

Scruggs is the “newgrass” movement, made popular

by modern bluegrass artists like Sam Bush and Bela Fleck.

And while today’s newgrass artists may share roots

with traditional bluegrass musicians, the similarities

end there, Stanley said.

“They don’t play traditional bluegrass,”

he said. “I think they might be in a different category.”

And it’s a category Stanley admits he could live

without.

“I don’t care for it,” he said. “I’m

more traditional. I think they went a little too far out.

And I think Bill (Monroe), if he were living today, would

feel the same.”

And while the newgrass scene grows, Stanley said he is

content to keep on doing what he’s been doing, albeit

at a somewhat slower pace than he’s accustomed to.

“I typically do 180 to 200 shows a year,”

he said. “I have cut down a lot. I’ll be doing

about half that this year.”

However, this is not to say Stanley, who has some 185

albums to his credit, will be slowing down with his recording

career.

“I just signed a contract with Columbia for 6 CDs,”

he said. “I made one and I’ve got to make

another in 30 to 60 days.”

Stanley said in addition to featuring a capella and “old-time

songs,” the upcoming release will be a tribute to

the Carter family, considered the first family of country

music and forebearer of June Carter-Cash.

“They recorded in 1927 from the same county that

I’m from,” he said. “I heard them when

I was a little boy.”

As for the show he intends to bring to Durango, Stanley

said his fans can expect to hear exactly what they came

for.

“I will bring along traditional bluegrass, the

way it was when it started and the way it should be,”

he said.

|