|

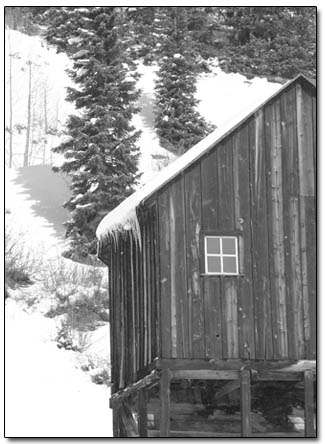

| Old mine sites, like this one north of

Silverton, are being blamed for sullying the waters of the

Animas River and have been targeted for cleanup./Photo by

Todd Newcomer. |

Ash and silt have consistently

put local water quality in the headlines in recent months. However,

hidden contaminants have been flowing through the Animas River

since the turn of the century and earlier – the leach

of natural mineral deposits and toxins from hundreds of former

mines and their associated waste. One local group, the Animas

River Stakeholders, has been working for nearly a decade to

reduce the metal load and enhance the water quality of the Animas.

The Forest Service also will be trying its hand at improving

local water quality with plans for its first large-scale, mine

cleanup, but there are concerns that the federal agency may

not be up to the challenge.

Bill Simon, Animas River Stakeholders Group watershed coordinator,

explained that from its source tributaries in and around Silverton

to its confluence with the San Juan River in New Mexico, the

Animas River is tainted with heavy metal and acid load. The

river contains traces of aluminum, cadmium, iron, copper, magnesium,

lead and zinc, among other metals.

“There’s a lot of natural leach, and the river’s

been further degraded by historical mining practices,”

Simon said. “The river is impacted all the way down to

its confluence with the San Juan in New Mexico.”

The Animas River Stakeholders Group (ARSG) is a volunteer organization

that was created in 1994. It has worked to combine public, private

and citizen efforts to improve the water quality and aquatic

habitats of the Animas. The formation of the group was a response

to the watershed’s failure to meet requirements of the

Clean Water Act and frustration with bureaucratic efforts to

improve local water quality. Simon said that because of the

efforts of the stakeholders and natural changes, the Animas

River now meets requirements as it flows through Durango. However,

the upper basin is still in need of big help.

|

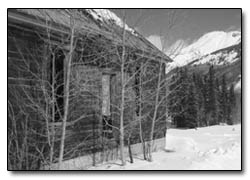

An abandoned mine structure near Red Mountain

Pass. Heavy metal load in the Animas has been

traced to old mine sites. /Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

“In Durango, the water has cleaned up to the point where

we’re in compliance with the Clean Water Act,” he

said. “It could still be better, and the upper basin is

not in compliance. Certain streams there have no life.”

In collaboration with Sunnyside Gold Corp., the stakeholders

group has facilitated partial clean-ups on Silverton-area mines

with names like Galena, Hercules, San Antonio and Carbon Lake.

The total price-tag has come to $23 million. Prior, the stakeholders

had evaluated roughly 1,500 different mine sites in the Silverton

area and highlighted 34 draining mine adits (horizontal shafts)

and 33 mine waste sites in need of clean-up. Simon said that

eliminating these sources of pollution will eliminate 90 percent

of the pollution load, and the group is working on a 20-year

timeline to come into compliance.

“The $23 million did a lot of work on sites that would

have made the list,” Simon said.

Early last month, the Animas River Stakeholders Group took

another step toward compliance with the purchase of water rights

and easements on the Carbon Lake ditch. Located near the summit

of Red Mountain Pass, the ditch had funneled water out of North

Mineral Creek and the watershed, over the pass and into the

Uncompahgre River. With the purchase, 15 cubic feet per second

of flow will be restored to the creek and dilute the metal load.

In addition, cleanup has begun on the Kohler Mine near Red Mountain

Pass a proven contaminator of North Mineral Creek.

The Brooklyn Mine northwest of Silverton near the ghost town

of Gladstone is another mine on the group’s priority list.

The mine is moderately sized, but its waste was spread widely

over a hillside that is publicly owned National Forest. Consequently,

the stakeholders will not have a leading role in the planned

cleanup. The Forest Service is working on a proposal to clean

up the mine site and improve Animas River water quality. An

engineering evaluation has looked at options for closing adits,

rerouting or treating mine-drainage water, and removing, treating

or capping acid-generating waste rock. To this end, the San

Juan National Forest is currently accepting public comment on

the proposal.A0

Stephanie Odell, San Juan Abandoned Mines Coordinator, noted,

“We’re trying to determine if we’ll proceed

with the project.”

The Forest Service is looking at a two-pronged approach to

cleaning up the Brooklyn mine. First, Odell said that the mine

waste would be removed, placed in a pit known as a glory hole

and covered. “What we’re hoping to do is take some

tailings that are really hot and put them in a glory hole and

cap them,” she said.

Secondly, the water draining from the mine must be stopped.

Odell said there is suspicion that the water is entering the

mine through the glory hole, which is located on higher ground.

“Some people suspect that the water coming out of the

adit is coming from our glory hole above it,” she said.

“We’re going to cap it and see if the water stops.

It’s one of those things where you just have to see if

it works.”

The cost of the work is estimated at $245,000. However, Odell

is quick to remark, “I hate to even quote that figure

before a request for bids. There’s always room for that

to change.”

The Brooklyn Mine will represent a huge leap for the local

Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management, being the largest

mine reclamation the local agencies have ever undertaken. “These

kinds of projects have been done before, but the Forest Service

and BLM haven’t done anything like this yet,” Odell

said.

Simon said that the Animas River Stakeholders Group sees several

significant problems with the Forest Service plan and will be

commenting. “They didn’t do an engineering analysis,”

he said. “They did a preliminary engineering analysis.

What they’re proposing to do is questionable at best.”

Simon cited failure to invite local contractors as another

problem with the Forest Service plan. “One of the major

problems is it’s designed so that local contractors can’t

bid on it,” he said. “That’s a real problem

for a community like Silverton.”

Lastly, Simon said that federal agencies take a roundabout

approach to such projects, and once the work begins, they rush

through them. He said federal failure to address the watershed’s

ills was a primary reason the stakeholders formed in the first

place. “We generally take a much different approach,”

Simon said. “That’s in a nutshell why we formed.

We try to address these projects in a more practical manner.

They’ve kind of slam dunked these things in the past.”

For more information, see the SJNF Web site at www.fs.fed.us/r2/sanjuan

or call Odell at 385-1353.