|

FLC takes on Wilder classic

written by Missy Votel

|

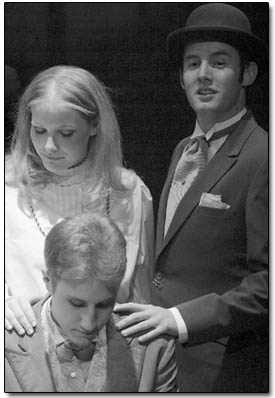

| Mrs. Gibb (Kristen Hathcock),

Dr. Gibb (Josh Martin) and George Gibb (Stephen Juhl)

in a scene from FLC’s production of “Our

Town.”/Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

Many may remember Thornton Wilder’s

classic play, “Our Town,” from their school

days. For several decades after its debut in 1938 –

the same year it won a Pulitzer – it was a mainstay

of community and high school stages across the country.

However, in recent years, possibly with the advent of

more high-tech, elaborate stage offerings, the rudimentary,

turn-of-the-20th-century play fell out of favor.

But as Americans begin a new century, rife with complexities

of global proportions, many find a longing to return to

simpler times and places, such as Thornton’s fictional

quintessential New England town, Grover’s Corners,

N.H., population 2,640. The play is currently enjoying

a resurgence on stages across the country, from Broadway,

where it stars Jane Curtain and Paul Newman, to the Fort

Lewis College stage, where the play will run for the next

two weekends.

According to director of the FLC production, Michael

Lawler, a Phoenix resident who did a stint as visiting

theater instructor at FLC in 1999-2000, the decision to

do “Our Town” was an easy one.

“I

had never read or seen it before, and I read it and fell

in love,” said Lawler, who also directed “Fortinbras”

at FLC. “As soon as I read it I knew it was the

right choice.” “I

had never read or seen it before, and I read it and fell

in love,” said Lawler, who also directed “Fortinbras”

at FLC. “As soon as I read it I knew it was the

right choice.”

He said the play is particularly relevant today, in the

wake of recent world events, including Sept. 11.

“It’s a play that celebrates the interdependency

of a community and a moral value system that is no longer

in place,” he said. “Twenty years ago people

would have looked at this play and said, ‘Oh, come

on.’ But the play celebrates community love and

hope, and we yearn today for that kind of love.”

Although the play is set in New England, in an era predating

cars or television, Lawler said it is a timeless piece

that transcends such barriers. While the play is called

“Our Town,” it may as well be “Any Town.”

“It’s the story of an all-American small

town,” Lawler said.

At its most basic, “Our Town,” is a story

of boy meets girl, centering on the lives of childhood

sweethearts George Gibb and Emily Webb and their respective

families. However, as the play progresses, it delves much

deeper.

“It’s a play that celebrates life and day-to-day

events that we are so busy that we can’t acknowledge,”

said Lawler.

Wilder drives this point home with the utter simplicity

of the set. There are no props in the play – save

for two dinette sets, each denoting the kitchens of the

respective families; a few rows of church pews; and two

step ladders. All actions in the play are pantomimed,

something Lawler had to teach to his cast of full-time

students.

“The whole cast had an exercise in pantomime and

techniques,” said Lawler, who took his cues from

a movement teacher at Arizona State University. “We

worked on that the first week.”

While one may think a play without props would be distracting,

Lawler points out is has the opposite effect.

“It allows the play to move more fluidly and focuses

attention on relationships in the play,” he said.

Indeed, Lawler is right. From the first scene, when the

Stage Manager, played by Eagle Young, who acts as play

narrator and commentator, gives a sweeping overview of

the town, imagination takes over. As the action shifts

to the morning routine of the Webb and Gibb families,

no props are needed to decipher that the respective matrons

are stirring batter, flipping pancakes and pouring hot

coffee.

The play, which spans three acts and 12 years, opens

around the kitchens of the families. It is here that the

audience is introduced to the main players, a wide-eyed

Emily, played by Kelly McDonald, and a lanky, young George,

played by Stephen Juhl. The main cast is rounded out by

the children’s families: Tara Sheehan and Herschel

Warner, who play Emily’s parents, Mr. And Mrs. Webb;

and Kristen Hathcock and Josh Martin, who play Dr. and

Mrs. Gibb, the parents of George. Emily and George also

have siblings: Wally Webb, played by Andrew Hall, who

makes a limited appearance, and George’s younger

sister, Rebecca, played by Anna Pierotti, who also has

a smaller role.

As the opening day wears on, we are given a glimpse into

the everyday life of the characters and the town: the

milkman and paperboy make their morning deliveries; Mrs.

Gibb strings beans from her garden; Dr. Webb returns from

attending a birth; and George and Emily discuss homework.

The young players do a notable job of performing their

daily routines with just the right amount of self-awareness,

neither underplayed nor over the top. Juhl, in his knickers

with a baseball typically clenched in fist, fits the part

of a gangly teen on the verge of manhood. McDonald, with

a smart red bob and soft voice, comes across as a confident

yet sweet Emily, a bright girl with a slightly dreamy

side.

Perhaps most commendable are the performances of the

young actors entrusted to play the parents. Hathcock capably

takes on a matronly, doting persona of someone twice her

age as she admonishes her overworked husband to get some

rest, and Sheehan brings a lightness and humor to her

role as the nurturer of the Webb clan.

“I would rather have my kids healthy than bright,”

she says while scolding them to eat their breakfast slowly

before rushing off to school.

Likewise, Martin is convincing as the likable but earnest

town doc, and Warner, with his jolly disposition and white

socks, does a good job as the bumbling and oblivious but

good-hearted editor of the town paper.

Perhaps the most daunting role in the play is that of

the Stage Manager, who must deliver several long asides

and commentaries, all while appearing personable and relaxed.

Young does an impressive and unflinching job of looking

straight into the eyes of his audience as he delivers

his lines in a genuine, welcoming manner. However, it

may be possible that he knows his lines a little too well.

A few times he tended to speed up his delivery, which

made it difficult to understand all that he was saying.

Nevertheless, he does a fine job of guiding the audience

through the various acts of the play, growing increasingly

philosophical as the play wears on.

“The play gets serious from here on,” he

tells the audience at the start of the second half of

the play, which chronicles the marriage of George and

Emily, as well as Emily’s untimely death.

Indeed, as we enter the third and final act, nine years

after the wedding, the play takes on a somber note. We

find things have changed since we last visited Grover’s

Corners. Not only have we lost a few key characters along

the way, but Fords have replaced horses; people have begun

locking their doors out of fear; and the town has become

generally “citified” in the words of Dr. Gibb.

“I remember when dogs used to sleep in the streets

all day long,” bemoans the Stage Manager.

However, he later points out that such changes are only

superficial.

“On the whole, things don’t change that much

around here,” he said. “There’s something

that’s eternal about all of us.”

We learn just how eternal as we venture with Emily, who

died in childbirth, from the afterlife to revisit her

12th birthday in an effort to savor one last, ordinary

scene from her life. To her credit, McDonald, in wedding

dress, is neither hysterical nor preachy as she tries,

unsuccessfully, to engage her family in breaking from

their daily routines to enjoy the simplicity of life’s

pleasures at hand.

“Do any human beings realize life while they live

it?” an older, wiser and frustrated McDonald asks

her fellow residents in the afterlife.

Sadly – except in the case of saints and poets

– the answer is no, we are told by a pensive Stage

Manager as the sole spotlight over our heroine fades to

black.

It is a simple ending to a simple play – allowing

us to give pause to ponder and appreciate the simple thing

we call life.

|