|

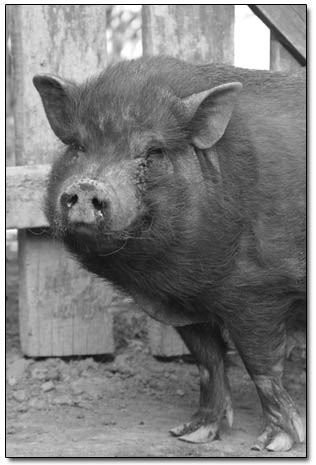

She's no Babe, but beneath that rough

exterior lies a lovable pig

written by Rachel Turiel

|

| Georgia, the pot-bellied pig,

poses for the camera in her yard on Durango’s

west side on Monday./Photo by Todd Newcomer. |

This is the routine: I squat eye level with the pig outside

of her split-rail fence, pushing broccoli peelings through

the spaces between splintered boards. Georgia pulls on

the vegetable scraps from her side of the fence, and with

a motion that involves gums, lips, frothy saliva and a

few weathered teeth, the broccoli stalk systematically

begins to disappear. In pure mastication nirvana, her

mouth hangs open like a hatch door. I lean forward to

study her face, and her breath hits me like a grassy meadow.

Georgia is a pig of the pot-bellied variety. She’s

not pink and white with a soft, squishy belly. She’s

a big, bristly, black hog with industrial strength nipples

that hang from her chest like a mother’s badge of

pride. In winter, her wiry hair stands up in a bouffant

around her head in a style nostalgically reminiscent of

Elvis. And here’s the kicker: She lives in town,

near Needham Elementary School, amongst blazing street

lights and traffic crossing guards. And though there are

numerous animals in the neighborhood – cats prowling

fence lines, dogs barking from back yards and even deer

and bear who leave sign in her dirt alleyway – Georgia

seems sorely out of place.

It was summer when I first discovered Georgia lounging

in the hard pan of a drought year. She stood as I cautiously

approached, heaving her girth up off the dirt and letting

it settle on four delicate legs, anchored to the ground

by her fanciful hooves.

It wasn’t long before my husband, who spent his

first five years on a farm, started saving vegetable scraps

in a mason jar in the fridge. “For the pig,”

he explained, an act that held great significance in my

mind as a portent of future child nurturing. And so, once

a week, mason jar full of carrot tops, culled kale leaves

and the peelings of broccoli stalks, we’d set out

to feed the pig.

It is Georgia’s snout that fascinates me most.

It seems all her senses are distilled into this muddy

proboscis, flexing and relaxing as it constantly nudges

the air in front of her. Her dark soulful eyes are tiny

pebbles nestled in folds of tough skin, peering out above

colonies of dirt barnacles lodged onto her snout. The

snout inhales slimy spinach leaves, and when I run out

of food she throws her weight up against the fence in

protest.

|

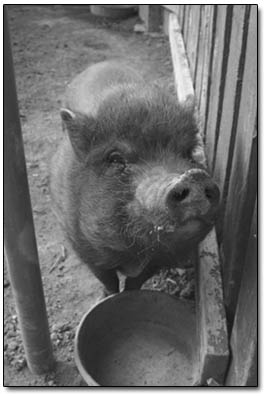

| Georgia,

who is now 6, was adopted by a Durango resident

for $1 at the Sale Barn in Aztec two years ago./Photo

by Todd Newcomer. |

The summer we met Georgia, we continued to fill the mason

jars with scraps, sneaking up to her fence via dirt alleyway

and feeding her surreptitiously. One summer evening we

brought our friend Ben down to observe the neighborhood

oddity. With overflowing mason jar in hand, we came upon

a backyard barbeque at Georgia’s house. We had to

come clean.

Georgia has history; her known story can be traced back

two years ago, when her guardian Lynette bought her at

the Sale Barn in Aztec and saved her from being put down.

The bidding began at $1 and ended at $1, with Georgia

riding home in Lynette’s horse trailer to Lynette’s

mother’s house in town. Lynette, her husband, Kyle,

and her mom, Loretta, have occupied the house while in

the slender backyard roams Georgia. For months, Lynette

rubbed healing oil into the pig’s then-hairless

skin and took her on walks in the neighborhood. The city

allows this on the distinction that Georgia is a pet,

rather than livestock. However, this pet isn’t quite

like the family golden retriever.

“She’s ornery,” Lynette warned us.

“She’ll charge you.”

“I don’t go into the backyard,” Loretta

corroborated, “she tried to take my hand off once.”

It was all perfectly believable coming from this mud

crusted mass of snout and backside with soulful eyes;

both sweet hearted and dangerous.

We continued to feed her, always from behind the fence.

This all went well until the Thanksgiving Day Debacle.

Festivities began early with David mixing Bloody Marys

at noon. The ubiquitous mason jar was full, so a party

of four set out to give Georgia the Thanksgiving meal

she deserved. Chris noticed that Georgia’s water

was frozen solid in her bowl, and despite discouragement

from the others, he jumped the fence. Georgia placidly

ate while Chris liberated her water, not seeming to notice

the 6-foot, 180-pound man in her yard. Task complete,

this would have been a fine time to exit the hog trough,

but curiosity got the better of him. Chris asked: “I

wonder if pigs are like dogs. If you touch ’em while

they’re eating will they go after you?” Chris,

a rural Southern boy with plenty of years’ experience

around animals, had been well warned about Georgiaaggressive

ways. Whether he was bolstered by the Bloody Marys or

the audience on the other side of the fence (one member

was rumored to have said, “I’d love to see

you get chased by that pig – it’d make my

day”) is all speculation. Chris leaned forward and

gave Georgia a pat on her generous rear. In a fury of

stubbly blackness, the hog turned and latched her teeth

onto Chris’s left leg, breaking through his working-man’s

overalls to delicate human skin beneath. When all was

said and done, Georgia had left a 6-inch gash.

Pot-bellied pigs had a wave of popularity in the ’90s

that ended with thousands of neglected and abandoned animals.

Cute and tiny as infants, pigs would grow up to destroy

people’s houses and often become aggressive. Like

dogs, pigs have a complex social structure and need a

lot of attention and affection. When they aren’t

properly socialized and exercised, they can become territorial

and mean. The average lifespan for a pot-bellied pig is

12 to18 years (Georgia is 6), and they are considered

the fourth-most intelligent animal, after humans, primates

and dolphins.

|

| Photo

by Todd Newcomer |

These winter days, I see Georgia in the mornings mostly,

en route to work. It’s 9 a.m. when I stand in the

frozen shadow of Loretta’s ranch style house, a

bag of broccoli stalk peelings in hand. Georgia is slow

to rise, and for a moment, I stand at the fence shaking

my bag of scraps like a tambourine, whistling with all

my might to project my voice to the dog igloo in which

she sleeps at the far end of the yard. Suddenly something

snaps in her pig brain, and she is up and snorting. It

seems to boil down to: Food. Over there. Mine. She shimmies

out of her igloo and comes running toward me, sniffing

and spitting hot air like a geyser through that mud-covered

opening in her face.

Lately I find Georgia waiting for me by the fence, and

a feeling of pride in our growing friendship makes me

all the more dedicated to

our morning time together. “Feed Pig” has

entered my to-do lists, and our household broccoli consumption

has increased while offerings for our compost pile steadily

shrinks. As Georgia nibbles on cabbage cores, I resist

the urge to scratch her bristled bouffant, reminding myself

that all good relationships have some boundaries.

|