|

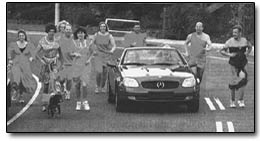

British-inspired pasttime gives

new meaning to 'making a beer run'

written by Missy Votel

So you think you’ve conquered the

gnarliest physical feats Snowdown has to offer, contorting

your limbs into an overstuffed outhouse, taking a cream

pie in the face and ski joring ‘til your arms hung

like limp noodles? Well, before you hang up your conga

shoes for another year, the slightly twisted minds at

Snowdown announce a new entry in the endurance and debauchery

department: the first official Snowdown Hash House Run.

Despite a name that may indicate otherwise, the pastime

of hashing involves nothing illegal – just runners,

or “harriers,” and an occasional cold adult

beverage, said event planner Matt Kelly. The harriers

are broken down into two groups: the “hares,”

a select group of ringers that leaves a 3-5-mile trail

of flour for the rest of the runners, or “hounds,”

to follow. The concept is simple: the hounds follow the

trail left by the hares to a locale where merriment and

jocularity ensues. However, as is the case with most travel

adventures, getting there is another story – and

half, if not all, of the fun.

“We

call ourselves a drinking club with a running problem,”

Kelly said. “It’s a fun-loving, irreverent

group.” “We

call ourselves a drinking club with a running problem,”

Kelly said. “It’s a fun-loving, irreverent

group.”

According to Kelly, almost anything is free game in a

typical hash course, including hill, dale, forest, chainlink

fence, shopping malls and even an occasional water hazard.

“I won’t promise that they won’t cross

the river,” he said.

The challenge is further confounded by false trails left

by masochistic hares in an effort to throw off the pack.

All of this is advantageous to the hares, who despite

a 15 minute headstart, sometimes get caught, quite literally,

with their pants down.

“All kinds of nasty things happen to the hares

if they’re caught,” he said.

As if the prospect of public humiliation for their peers

isn’t enough, the hounds also are spurred on by

one of the oldest incentives known to humankind: beer.

According to Kelly, beer is hidden along the hash course

and marked by a “BN” for “beer near.”

“It

makes ’em run harder and faster to get to the beer,”

he said. “It

makes ’em run harder and faster to get to the beer,”

he said.

And while the sport does involve speed, Kelly said being

the first to finish is not the point of a hash. In fact,

it behooves slower hounds to hang back, letting the FRBs,

or front-running bastards as they’re called, do

all the work.

“It probably helps not to be a runner,” he

said. “That way you let everyone else run ahead

and go down all the false trails. They end up exhausting

themselves, and this benefits the slower runners.”

He also said hashes are split into ability categories,

with longer, steeper and more difficult “Eagle Trails”

for the more hard-core runners and shorter, easier “Turkey

Trails” for the less inclined runners.

Although this will be the first official Snowdown Hash,

Kelly said an unofficial one was held at last year’s

event. It was put on by Kelly and a group of locals with

the help of about 40 members of a Front Range hash group.

He said between 60 and 70 hashers participated in last

year’s run, and that he expects similar crowds at

this year’s hash, a series of three runs.

Kelly said last year’s event was such a success

that afterward, he and his rag tag group were branded

an official hash club, one of 13 in the state.

“We’re pretty loosely organized,” he

said. “Hashes only happen when someone gets inspired.”

Nevertheless, the pastime has gained a solid foothold

elsewhere, with more than 1,500 hash groups holding regular

runs worldwide, according to the World Hash House Harriers,

the closest thing to a governing body the sport has. According

to the group, the rudimentary roots of hashing go back

possibly as far as the activity of running itself. However,

today’s format follows that of an enterprising English

ex-patriate who organized a hash in Malaysia in 1938.

The group took its name from the sub-par offerings of

the Royal Selangor Club (hash house is slang for “cheap

restaurant”), where many expatriate Brits would

dine. According to the World Hash House Web site, the

weekly runs were followed by copious amounts of the local

brew, Tiger beer.

Today, the sport has earned a cult-like following in

the United States, operating for the most part under the

radar screen of mainstream society (although one group

in Wichita, Kans., gained notoriety when flour used in

a hash was mistaken for anthrax). In fact, many veteran

hashers go by their well-earned hash names, which usually

stem from an incident on the hash trail. The pseudonyms,

which range from “Bone Ranger” (a local hasher)

to “Poopatrooper” and “Aqua Lungs”

(use your imagination) are used to protect hashers from

their alter-egos, Kelly said.

“Most are professionals,” he said. “The

names started as a way to hide your identity.”

Nevertheless, Kelly insists hashing is something that

almost anybody with a sense of humor and a pair of running

shoes can appreciate.

“It’s a noncompetitive event,” he said.

“You don’t even have to be a runner. It’s

all for fun and drinking. And you don’t even have

to drink to enjoy it 85 but it helps.”

|