|

by Will Sands

It

began with a ragged postcard from an old college friend. The

card had come to me from India, and judging from its appearance,

it had been in transit for some time. It

began with a ragged postcard from an old college friend. The

card had come to me from India, and judging from its appearance,

it had been in transit for some time.

“This last year was pretty good to

me. I was a lucky bastard (not counting three self-diagnosed

cases of giardiasis - I won’t indulge you with the tell-tale

symptoms). I only had to pay baksheesh once at the Pakistani

border, but that’s a long story.”

The card ended abruptly, hanging in my hands

like more of a clue than correspondence.

However, a couple weeks later the blanks

were filled when I received a call. Indeed, the postcard had

been in transit for some time. My friend was back at home in

Florida for a spell and eager to tell of his year exploring

the back roads of Asia.

Apparently, mom was paying because he rambled

on for a couple hours.

He told of his traverse across Europe, crossing

the Bosphorus and his first descent into the Middle East. Courtesy

of duel citizenship, he was able to skip through Iraq and was

eventually welcomed into Iran, where he holed up for four months

in the land of Ayatollah Khomeini. During that time, he was

asked to marry a 16-year-old female, seriously considered converting

to Islam and, as testament to this urge, slaughtered a lamb

to celebrate the end of the Islamic month of fasting, Ramadan.

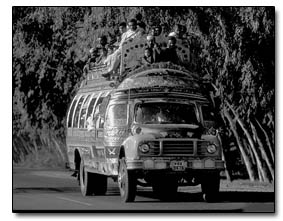

He elaborated on crossing Pakistan by bus,

his life in the hands of a driver who habitually smoked heroin

as he sped along narrow passes with elevations in excess of

our highest peaks. With glory in his voice, he mentioned transcendent

experiences on the Baltoro Glacier, the home of K2 and the Gasherbrums.

He finished out his tale and his journey

in India, speaking highly of Ladakh, a hold-out of Tibetan Buddhism,

and not-so-highly of Siddhartha’s birthplace, now a crime-ridden

backwater.

So ended his trip and our conversation,

and after two hours, I realized that I had barely spoken. My

half-assed comments were mainly kept to “wow,” “all-right”

and “cool.”

At the time, it didn’t seem right

to speak of skiing powder at Wolf Creek, spending long weekends

in canyon country or bringing a new human into the world. At

the time, my experiences felt empty, and I was honestly more

than a little envious. He was living a dream that I had once

embraced, the dream of endless wandering and bumming across

the globe. I was the guy who gagged down three-and-a-half years

of Arabic and countless eastern religion classes. I thought

to myself that I should have been at that Ramadan, walking the

streets of Tehran and on that bus to Baltoro.

But after I hung up the phone, I thought

twice about the tone of his voice and desperate nature of his

words. It was true that he had lived a great dream, traversing

Asia by foot and bus. But I realized that living that great

dream had come at a heavy price.

He set out with limited knowledge of Asian

culture and no understanding of the half dozen languages and

hundreds of dialects he crossed. He was not wandering, but staggering,

and it seemed that in his extravagant exploits, he had but scratched

the surface. Throughout he remained only a visitor, a tourist.

And judging from our conversation and his

diarrhea of the mouth, he was very much alone during those 12

months, very much apart from humanity. During a simple phone

call, he latched onto me like a drowning man, starving for companionship

and teetering on the brink of madness. Rather than the jovial

friend I remembered, I was treated to a one-sided lecture from

a man who was fresh out of 365 days of solitary.

And thinking back on our conversation, I

should have expanded my comments well beyond “wow”

and “cool.” I should have spoken of the beauty of

sharing a random conversation on Main Avenue, told of venturing

on seemingly endless rides with great friends and mentioned

the pleasure of waking to look out at the same red cliffs and

noticing new alcoves. I should have explained that in my experience

some of the best learning comes from exploring one place in

depth and mentioned that it’s best to put your roots down

in people. I might have done this and more.

But, I know that friend of mine is still

out there, cut loose of entanglements. The last I heard he was

off to teach English in Japan. And there’s still a big

part of me that wants to be at that border crossing or squeezed

into that tight bus.

But I take solace in knowing that I’ve

found a big piece of what I’ve been searching for. I hope

that one of these days he finds his.

|