|

written by

Missy Votel / photos courtesy Jonathon Thompson

There

is perhaps no setting more befitting Dolores LaChapelle

than her simple wood cabin nestled on a snow-packed Silverton

street. Wearing an Outward Bound T-shirt and a long, plaid

wool skirt with her signature braid – now a brilliant

silver – hanging loosely down her back, she sits

in a sunny nook, surrounded by mountains. Out the window

behind her, the sun is setting over Sultan. To her right,

Kendall looms. On its shadowed lower flanks, a lone skier

rides the town’s rope tow. There

is perhaps no setting more befitting Dolores LaChapelle

than her simple wood cabin nestled on a snow-packed Silverton

street. Wearing an Outward Bound T-shirt and a long, plaid

wool skirt with her signature braid – now a brilliant

silver – hanging loosely down her back, she sits

in a sunny nook, surrounded by mountains. Out the window

behind her, the sun is setting over Sultan. To her right,

Kendall looms. On its shadowed lower flanks, a lone skier

rides the town’s rope tow.

Before the interview can commence, LaChapelle lays down

the rules. Whoever sits in the west-facing seat must don

sunglasses to shield her eyes from the glare.

I dutifully fish mine out, however unconventional the

request may be, thankful for the reprieve from the late-afternoon

rays.

Outside, the snowbanks have already reached respectable

heights, thanks to the most recent storm that dropped

about a foot of snow on the town. Inside, LaChapelle is

reading a paper and shaking her head in disapproval.

“Seventy-one dollars to ski at Vail,” she

says in disgust. And while the price is steep, the veteran

skier admits the steep price won’t keep her away,

“I wouldn’t ever ski Vail anyway,” she

says.

If she sounds disdainful, it’s for good reason.

LaChapelle spent the better part of five decades skiing,

or more specifically in pursuit of the purism offered

by untracked powder. In fact, she knows the subject so

well, she published a book, Deep Powder Snow, on it in

1993.

The septuagenarian not only knows skiing history, she

has lived it. When Aspen fired up its first chairlift,

she was there. When Alta, Utah, was but a tiny speck on

the map, she was there, too.

Wooden skis? She had them. Avalanches? Survived those,

too. She will also tell you how many of the places she

loved have been ruined by commercialism and greed. And

now, she watches with a knowing eye as more development

is about to take place down the road from her home of

30 years.

“They’re going to develop that whole corridor,”

she says of the swath of mostly empty land between Durango

Mountain Resort and Cascade Village. “I guess you

knew it had to happen some day.”

Originally from Denver, LaChapelle cut her teeth skiing

Loveland Pass on a pair of World War II Army surplus boards.

In 1947, she graduated college early with the intent of

finding a teaching job in a mountain town and landed in

Aspen. And although today the former mining enclave is

synonymous with wealth and glitz, LaChapelle says the

old Aspen was anything but.

“They had just built the lift,” she said.

“It was before skiing became fashionable. At the

time skiing was not a big money-maker. I know it seems

bizarre, but everyone was just there to ski.”

LaChapelle took advantage of cheap ski lessons and soon

found herself not only teaching skiing but hiking the

steeps of Bell Mountain (which at the time was not lift

served) in search of untracked powder. It was during her

third and final year in Aspen that she started a correspondence

with Ed LaChapelle, whom she met on a summer climbing

trip in Canada. A year later, the two married, and Ed’s

work as an avalanche researcher took the couple to the

Swiss Alps.

The change couldn’t have come at a better time for

LaChapelle, who says she sensed the carefree days of Aspen

coming to an end. She said people had begun to realize

money could be made in skiing and were taking over the

small town.

And while a chapter in skiing history had closed, in her

eyes, another had just opened: the invention of metal

skis.

“Howard Head ruined skiing,” LaChapelle said,

partly in jest. Much like the shaped skis of today, LaChapelle

said the 1950 introduction of wood-core metal skis (the

predecessors were made of solid wood) revolutionized the

sport – and not necessarily for the better.

“Now anyone could ski,” she said.

After the stint in Europe, Ed’s job eventually landed

the couple in Alta, which they called home for the next

20 years.

“The greatest snow on Earth,” LaChapelle says,

well aware she may sound like a “Ski Utah”

billboard. “But it’s true,” she insists.

During the ensuing seasons at Alta, which included many

brushes with avalanches, including one that left her hospitalized

in a body cast, LaChapelle became renowned in skiing circles

for her powder skiing prowess. She even earned the nickname

“Witch of the Wasatch” for her uncanny ability

to predict storms. However, much like her tenure in Aspen,

the good times at Alta came to an end with the opening

of Snowbird in the early ’70s. Knowing that all

of Ed’s time would be taken up with control work

rather than his true love – research – the

couple packed their bags, this time headed for the San

Juans.

Although LaChapelle admits it was hard to say good-bye

to Alta’s famous fluff in favor of the equally infamous

San Juan cement, she said there was enough terrain and

powder surrounding her new home to survive. In fact, it

could be said that she even thrived – becoming a

regular fixture in the backcountry ski scene. She even

pioneered a ski descent of a gully near Sam’s, a

popular backcountry shot near the abandoned enclave of

Chattanooga. Nevertheless, LaChapelle dismisses the recurring

suggestion that she was the first female extreme skier.

“I’m not extreme. No way,” she says.

“I was the best female powder skier, but there was

nothing extreme about it.”

In fact, the competitive nature of extreme skiing runs

precisely counter to LaChapelle’s entire theory

of skiing and life in general. If anything, LaChapelle

was one of the first female soul skiers.

For her, skiing wasn’t about conquering the mountain,

she says, but surrendering herself fully to the forces

of gravity, rock and snow. She always realized that her

love of powder went deeper than an entertaining hobby

or pastime. Rather, it gave her a unique connection to

the world. It was an escape from what she refers to as

the “rational hemisphere,” the part of the

brain that constantly seeks reason.

“Anything that gets you out of the rational hemisphere

is good,” she says. “And skiing does that,

as long as you’re not out to prove something or

how good you are.”

However, it wasn’t until many years later, when

California philosophy professor Paul Shepard coined the

phrase “Deep Ecology” that LaChapelle had

a name to attach to her concept.

She

immediately became an advocate of Deep Ecology, which

espouses the virtue of humans living in harmony with nature,

and once again found herself at the forefront of a revolution.

Today, Deep Ecology is a worldwide environmental movement

that counts famous redwood-sitter Julia Butterfly among

its followers. LaChapelle has written several books on

the subject, which are standard reading in many college

courses, and has traveled the world lecturing on the subject. She

immediately became an advocate of Deep Ecology, which

espouses the virtue of humans living in harmony with nature,

and once again found herself at the forefront of a revolution.

Today, Deep Ecology is a worldwide environmental movement

that counts famous redwood-sitter Julia Butterfly among

its followers. LaChapelle has written several books on

the subject, which are standard reading in many college

courses, and has traveled the world lecturing on the subject.

Yet, despite her fame and success, LaChapelle actually

shuns the limelight, preferring the isolation of Silverton.

“I try to hide out here so people can’t find

me,” she says.

And to make it even more difficult, she has no Internet,

no fax machine and no TV.

“I have enough people calling for interviews, and

I have plenty to keep me busy,” she said. “If

I had all that I’d go crazy.”

This is not to say that LaChapelle prefers to stick her

head in the snow, oblivious to the world around her. Quite

the contrary, she has a voracious appetite for reading

(or “finding answers” as she calls it.) The

walls in her house are lined with books, and she gets

up from the interview no less than three times to fetch

various works to refer to.

And although she gave up skiing 10 years ago because of

a hip injury (a lasting reminder of the Alta avalanche)

LaChapelle stays physically active as well. She has a

pair of snowshoes for touring the backcountry and is a

devout practitioner of tai chi, which she teaches once

a week.

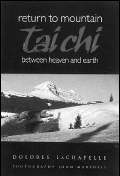

She has penned a book on tai chi as well, Return to Mountain:

Tai Chi Between Heaven and Earth, which is due in stores

any day. It will be LaChapelle’s seventh book, nevertheless,

she is reluctant to call herself a writer, preferring

the term “information dispenser.”

“I didn’t want to be a writer,” she

says. “I was just trying to save the world, but

now I think there’s no hope.”

Yet, there is something about this woman, who has endured

7-foot wooden skis, several avalanches and a lifetime

of mountain living, that tells you she is not about to

give up the fight.

In fact, she admits that if there is any hope, it will

come through practice of this ancient form of martial

art.

“All you need is a little outdoors, and you do it

every day,” she said. “Eventually you will

fall in love with the place where you do it, and you’ll

do anything to save it.”

A constant reminder of what she’s working toward

is propped up in her house, near the front door for all

to see. It is the top portion of a log from South Mineral

Creek, split down the middle by lightning and worn smooth

as marble by years of human passage. LaChapelle herself

has used the log many a time to cross the stream. When

she noticed the bottom was rotting away, she lugged home

the top, which is now a banister.

“What I’m seeing there is hope,” she

admitted while rubbing her weathered but strong hands

along the well-polished surface, “humans and nature

working together to make something beautiful.”

|