|

written by

Amy Maestas

In

the aftermath of the Missionary In

the aftermath of the Missionary

Ridge and Valley fires this summer,

local artist Shan Wells held a

metaphorical mirror up to his life, attempting to recognize

how the fires’ destruction had changed it. This

was not a small mirror from a vanity case; it was enormous

– to capture both the breadth of Wells’ 6’3”

stature and his emotions.

Wells saw a lot: fear,

pain, loss and uncertainty; he saw raw wounds that

needed healing. Although Wells was not a victim of the

fires’ insidious path,

his inspiration was.

As

an illustrator and environmental sculptor, Wells’

art comes from nature – As

an illustrator and environmental sculptor, Wells’

art comes from nature –

literally and intellectually. He creates what some call

“eco art” or “land art,” a

movement largely popularized in the 1960s that focuses

on the connection

between humans and nature. His work might include leaves,

stones or flowers. Or it might include burnt twigs and

thick mud, which are part of his sculptures currently

on display at the Cordell Taylor Gallery in Denver.

Wells’ exhibit,

“burn works,” showcases five pieces he created

in response to the devastation of this summer’s

fires as well as past wildfires at Mesa Verde National

Park. The Mesa Verde fires inspired three pieces, Zygote,

Artifact and Arrested Languages, which he created last

year and displayed in Durango. They are, by Wells’

definition, more intellectual than intuitive. But this

year, he added two new pieces to his suite of art, both

of which carry a powerful punch of sorrow and rage, and

have deeper meaning because of their proximity to this

native Durangoan’s back yard.

The most dramatic, Plume

Drawing, is a black-and-white 7-by-10-foot triptych in

pencil and charcoal. It is a vast spiral of smoke rising

from an invisible landscape.

“This drawing

is about the uncontrollable energy of these plumes,”

says Wells. “Its size is meant to evoke the power

that was inside them.”

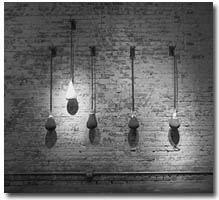

Swab is a 12-by-10-foot

sculpture of five auger-like farm implements wrapped in

organic cotton and supported by rusted poles. The swabs

are soiled with a slurry of mud and ash, which Wells collected

from the mudslides that deluged the valley after the fires.

“The

mud and ash from the mudslides were the color and consistency

of chocolate pudding,” he says. “I helped

people who were buried in mudslides. And when I got into

this mud, I noticed that it was like clotted blood. These

mudslides were like the land was hemorrhaging –

like the earth was trying to cleanse itself.” “The

mud and ash from the mudslides were the color and consistency

of chocolate pudding,” he says. “I helped

people who were buried in mudslides. And when I got into

this mud, I noticed that it was like clotted blood. These

mudslides were like the land was hemorrhaging –

like the earth was trying to cleanse itself.”

Swab, Wells says, conveys

the pain that comes after the fire and the need for wounds

to be tended to. One swab remains clean, however.

“This means that

the jobs of conservation and reclamation aren’t

finished, and won’t be for a long time. We also

have a job to do of rebuilding from these fires’

damage to our economy and to our social fabric.”

Wells grew up on East

Animas Road, so when the fires hit, along with his artistic

wellspring, many of his childhood memories went up in

smoke too. He spent much of his childhood picking chokecherries

and mushroom hunting on Missionary Ridge. Many of his

family members still live in the valley. Wells helped

his aunt evacuate her home and helped an uncle clear brush

on his property as a defense. This is why the two new

pieces in his sculptural suite are so particularly painful

and personal. However, these two pieces also are acting

as catharsis, Wells said.

In 1996, Wells, whose

father was a ranger at Mesa Verde, became interested in

learning about the effects wildfires have on nature. That

year and in 2000, he worked with firefighters to understand

the regeneration of the land destroyed by fire and in

turn incorporate it into his work.

“My art is about

conceptual ideas. It is also like a series of questions

about how humanity views nature, how we value it, interpret

it, label it,” says Wells.

“One of the main

things I look for in my art is how to bring us back to

the most basic thing, which is the earth. We use the earth’s

resources to separate us from it. But we shouldn’t.

If things are cut off, like water and snow, everything

else falls away. It only takes a shrug of the earth’s

shoulders for it to crumble.”

As Missionary Ridge

was crumbling under the heat, Wells says he wasn’t

thinking about how it would impact his art, nor was he

immediately aware of any inspiration for future works.

He was immersed in helping family, community members and

firefighters survive. He was also coming to terms with

his own emotions.

“I felt guilty

when the fires started,” he says. “I had wanted

to learn all I could

about what wildfires did to nature and the landscape.

So, when they started, I

thought to myself, ‘Well, here’s your opportunity.

Now you can learn all you

want to know.’ I didn’t want to learn this

way. But I have much more respect for this natural process

now.”

Beyond his own healing,

Wells also is concerned about healing the community. He’s

troubled by the divisiveness that emerged from the finger-pointing

and name-calling once the fires were under control. Blame,

he says, is not helpful. We all share the burden collectively.

“We came together

so beautifully during the fires, and now we’ve become

so

polarized,” he says. “Blaming each other isn’t

going to help us protect ourselves and the forest from

future fires.”

Wells is unsure whether

his two new pieces will be displayed in Durango, although

that’s his desire. But since they are intensely

personal works, and, he says, are in many ways incomplete,

he’s comfortable using them and any future burn

sculptures as salve on his own wounds.

“At the end of

the day, I’ve come not to hate the fires,”

he says. “But there’s

more I personally need to go through before I’m

finished with this.”

|