|

|

written by Jennifer

Reeder

It’s not every day that Durangoans have the chance to

“explore exciting possibilities of mask, puppet, dance

and shadow,” so that’s one reason to watch “The

Air Inside the Rose.” The show, brought to us by the Fort

Lewis Theatre Dept., consists of three performance pieces and

opens Friday.

It’s not every day that Durangoans have the chance to

“explore exciting possibilities of mask, puppet, dance

and shadow,” so that’s one reason to watch “The

Air Inside the Rose.” The show, brought to us by the Fort

Lewis Theatre Dept., consists of three performance pieces and

opens Friday.

“(The three pieces) all have different story lines, but

the motif that keeps coming back is that thing we want or desire

but for some reason can’t attain,” says Dr. Kathryn

Moller, who directs two of the pieces. “All of them explore

that in a very deep way.”

The theme is certainly explored in a deep and esoteric way –

David Lynch fans and people experimenting with hallucinogens

will eat this stuff up. Moller describes it differently: “It

might not be what people expect `85 but (it will please) theater-goers

looking for something different than what they normally see.”

It’s true – and all three pieces create a unique

theater experience in vastly different ways. The first piece,

“The Black Pearl,” utilizes 3-foot high puppets

and “shadow play,” or actors whose shadows are cast

on a lit backdrop. In this case, the shadow actors are Deborah

Wehmer and Caleb Creel, who move with precision and grace.

“The Black Pearl” also is distinctive because it

was written by Beth Osnes, an Indonesian theater scholar who

drew upon an ancient form of Japanese theater, “Japanese

Noh,” when she crafted her play.

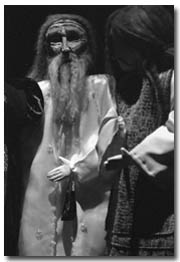

But the star of “The Black Pearl” is an elderly

female puppet (made of styrofoam and paint and operated by a

hooded theater student, Jill Davis) scarred by the death of

her young love, who drowned at sea. She is visited by an elderly

male puppet (operated by Eagle Young) who turns out to be the

spirit of her dead lover’s greedy boss. The pace is on

the slow side (though there should be pyrotechnics if all goes

well), and the dialogue seems like it might have been a dubbing

of a kung-fu flick: “I am she.” “Yes, I know.”

“Won’t you please come back in?”

Wehmer and Creel’s shadows perform the flashback scene

as the elderly  puppet

tells her story of lost love to the stranger. She was lonely

as a young girl until she caught a young man in her fishing

net, and they fell in love. He proposes with a black pearl he

hoisted while on the job as a fisherman/diver, explaining that

the black pearl is one of the ocean’s greatest treasures.

She tells him she wants a whole string of black pearls as proof

of his loyalty. The lover tragically dies trying to horde enough

pearls, which sets the stage for a dramatic turn of events –

and also provides the opportunity to practice cultivating empathy

for an inanimate object. puppet

tells her story of lost love to the stranger. She was lonely

as a young girl until she caught a young man in her fishing

net, and they fell in love. He proposes with a black pearl he

hoisted while on the job as a fisherman/diver, explaining that

the black pearl is one of the ocean’s greatest treasures.

She tells him she wants a whole string of black pearls as proof

of his loyalty. The lover tragically dies trying to horde enough

pearls, which sets the stage for a dramatic turn of events –

and also provides the opportunity to practice cultivating empathy

for an inanimate object.

The second piece is called “The Dreaming of the Bones,”

and was written by William Butler Yeats. Though best known as

one of the greatest poets in literature, Moller says he “felt

that he was more of a dramatist than a poet.”

For this dramatic foray, Yeats included some musical compositions

for words to be sung in parts, but Moller says it has been deemed

“unplayable.” Instead, she searched for dissonance

within his compositions, and Durango’s Lawrence Nass composed

original music for it, as well as the first piece.

His haunting music is played intermittently by flute player

Syneva Peters, while percussionist Matt McDonald might hit his

drum or shake a rattlesnake maraca. A chanting character might

suddenly sing a word in a dialogue, or the chorus might simultaneously

sigh and lower their arms the same way, or make wind noises

in between the actors’ lines. To be honest, the background

flourishes distract the viewer from Yeats’ words, like

“Even sunlight can be lonely here.”

The story line involves a lost man, Creel, who wanders onto

an ancient battlefield. Two 700-year-old ghosts, played by masked

Young and Wehmer, tell their story of causing a war because

of their affair – sometimes through dialogue, sometimes

through dance. Creel could end their sexual separation by forgiving

them, but instead he storms off, and they return to the ground.

The third piece, “Object of Screams and Whispers,”

initially seems like it will be fairly mellow – words

are projected onto a screen behind the stage about a fairy who

will give a tour of an island to members of a “vagabond

skiff” as recorded opera plays. But then Emily Flood rushes

down the aisle clutching and smelling white pumps while declaring

“I’m ready,” and things get interesting.

She’s followed by a colorful assortment of characters,

such as Kelly McDonald, who holds a plastic branch with leaves

in front of her face while asking, “Why are you looking

at me? I am not here!” or Matt McDonald, who fondles a

blue and red Nerf ball and murmurs, “No, it’s mine.”

There’s also a woman on a tether, Gina Shure; a man with

a bell and hat, Stephen Juhl, begging, “Just a little

bit of love, please?” and then chastising “Greedy!”;

Jill Davis, who tries to give away a fishing net; and a man

with a suitcase, Ian Hanson, who collapses on the stage.

But these props are symbolic – this is Object Theatre,

which Moller says is a  trend

in Europe right now. The piece was directed by guest director

Isabelle Kessler, who normally lives in France. trend

in Europe right now. The piece was directed by guest director

Isabelle Kessler, who normally lives in France.

Hanson not only inserts the only humor in the entire show, but

has an intriguing moment when he runs his fingers through the

sand in his suitcase and starts feigning orgasm – then

suddenly stops and says, “Until,” and leaves the

stage. The props – aka objects – all eventually

find their way to the suitcase as actors change their tunes.

For example, Kelly McDonald deposits her branches and runs offstage

declaring, “Yes, I am here. Can you see me?”

“The Air Inside the Rose” is not going to have broad

appeal, but it is certainly a one-of-a-kind performance. The

target audience is probably theater aficionados with the sophistication

to appreciate this ambitious project, but less-qualified critics

might also find it at the very least entertaining. And if anyone

out there is doing any Carlos Castenada-style experiments, attending

this show will provide very interesting fodder for your research.

One way or another, this is a performance you have to see to

believe.

|